. . . the existing government is ranked merely as one of the contending parties. The virtuous citizen is enjoined, not to come forward in its support, but to come forward at all events, either for it or against it. Positive and early action is all which is prescribed to him as matter of duty.

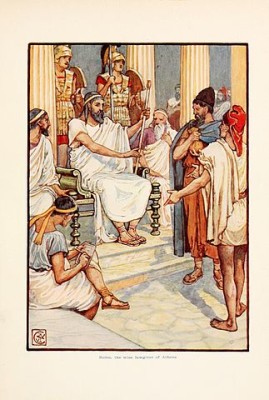

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Nothing was more likely to encourage aggression on the part of an ambitious malcontent, than the conviction that if he could once overpower the small amount of physical force which surrounded the archons, and exhibit himself in armed possession of the Prytaneum or the Acropolis, he might immediately count upon passive submission on the part of all the freemen without. Under the state of feeling which Solon inculcates, the insurgent leader would have to calculate that every man who was not actively in his favor would be actively against him, and this would render his enterprise much more dangerous. Indeed, he could then never hope to succeed, except on the double supposition of extraordinary popularity in his own person and widespread detestation of the existing government. He would thus be placed under the influence of powerful deterring motives; so that ambition would be less likely to seduce him into a course which threatened nothing but ruin, unless under such encouragements from the preexisting public opinion as to make his success a result desirable for the community. Among the small political societies of Greece–especially in the age of Solon, when the number of despots in other parts of Greece seems to have been at its maximum–every government, whatever might be its form, was sufficiently weak to make its overthrow a matter of comparative facility. Unless upon the supposition of a band of foreign mercenaries–which would render the government a system of naked force, and which the Athenian lawgiver would of course never contemplate–there was no other stay for it except a positive and pronounced feeling of attachment on the part of the mass of citizens. Indifference on their part would render them a prey to every daring man of wealth who chose to become a conspirator. That they should be ready to come forward, not only with voice but with arms–and that they should be known beforehand to be so–was essential to the maintenance of every good Grecian government. It was salutary in preventing mere personal attempts at revolution; and pacific in its tendency, even where the revolution had actually broken out, because in the greater number of cases the proportion of partisans would probably be very unequal, and the inferior party would be compelled to renounce their hopes.

It will be observed that, in this enactment of Solon, the existing government is ranked merely as one of the contending parties. The virtuous citizen is enjoined, not to come forward in its support, but to come forward at all events, either for it or against it. Positive and early action is all which is prescribed to him as matter of duty. In the age of Solon there was no political idea or system yet current which could be assumed as an unquestionable datum–no conspicuous standard to which the citizens could be pledged under all circumstances to attach themselves. The option lay only between a mitigated oligarchy in possession, and a despot in possibility; a contest wherein the affections of the people could rarely be counted upon in favor of the established government. But this neutrality in respect to the constitution was at an end after the revolution of Clisthenes, when the idea of the sovereign people and the democratical institutions became both familiar and precious to every individual citizen. We shall hereafter find the Athenians binding themselves by the most sincere and solemn oaths to uphold their democracy against all attempts to subvert it; we shall discover in them a sentiment not less positive and uncompromising in its direction, than energetic in its inspirations. But while we notice this very important change in their character, we shall at the same time perceive that the wise precautionary recommendation of Solon, to obviate sedition by an early declaration of the impartial public between two contending leaders, was not lost upon them. Such, in point of fact, was the purpose of that salutary and protective institution which is called the “Ostracism”. When two party leaders, in the early stages of the Athenian democracy, each powerful in adherents and influence, had become passionately embarked in bitter and prolonged opposition to each other, such opposition was likely to conduct one or other to violent measures. Over and above the hopes of party triumph, each might well fear that, if he himself continued within the bounds of legality, he might fall a victim to aggressive proceedings on the part of his antagonists. To ward off this formidable danger, a public vote was called for, to determine which of the two should go into temporary banishment, retaining his property and unvisited by any disgrace. A number of citizens, not less than six thousand, voting secretly, and therefore independently, were required to take part, pronouncing upon one or other of these eminent rivals a sentence of exile for ten years. The one who remained became, of course, more powerful, yet less in a situation to be driven into anti-constitutional courses than he was before. Tragedy and comedy were now beginning to be grafted on the lyric and choric song. First, one actor was provided to relieve the chorus; next, two actors were introduced to sustain fictitious characters and carry on a dialogue in such manner that the songs of the chorus and the interlocution of the actors formed a continuous piece. Solon, after having heard Thespis acting (as all the early composers did, both tragic and comic) in his own comedy, asked him afterward if he was not ashamed to pronounce such falsehoods before so large an audience. And when Thespis answered that there was no harm in saying and doing such things merely for amusement, Solon indignantly exclaimed, striking the ground with his stick, “If once we come to praise and esteem such amusement as this, we shall quickly find the effects of it in our daily transactions.” For the authenticity of this anecdote it would be rash to vouch, but we may at least treat it as the protest of some early philosopher against the deceptions of the drama: and it is interesting as marking the incipient struggles of that literature in which Athens afterward attained such unrivaled excellence.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.