We are told that after a short interval it became eminently acceptable in the general public mind, and procured for Solon a great increase of popularity–all ranks concurring in a common sacrifice of thanksgiving and harmony.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

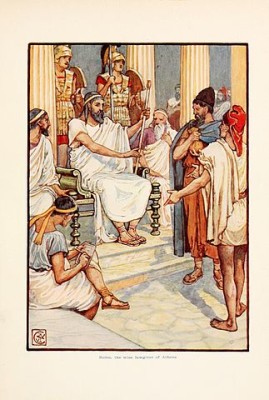

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It [Solon’s debt law -ED] swept off all the numerous mortgage pillars from the landed properties in Attica, leaving the land free from all past claims. It liberated and restored to their full rights all debtors actually in slavery under previous legal adjudication; and it even provided the means (we do not know how) of repurchasing in foreign lands, and bringing back to a renewed life of liberty in Attica, many insolvents who had been sold for exportation. And while Solon forbade every Athenian to pledge or sell his own person into slavery, he took a step farther in the same direction by forbidding him to pledge or sell his son, his daughter, or an unmarried sister under his tutelage–excepting only the case in which either of the latter might be detected in unchastity. Whether this last ordinance was contemporaneous with the Seisachtheia, or followed as one of his subsequent reforms, seems doubtful.

By this extensive measure the poor debtors–the Thetes, small tenants, and proprietors–together with their families, were rescued from suffering and peril. But these were not the only debtors in the state: the creditors and landlords of the exonerated Thetes were doubtless in their turn debtors to others, and were less able to discharge their obligations in consequence of the loss inflicted upon them by the Seisachtheia. It was to assist these wealthier debtors, whose bodies were in no danger–yet without exonerating them entirely–that Solon resorted to the additional expedient of debasing the money standard. He lowered the standard of the drachma in a proportion of something more than 25 per cent., so that 100 drachmas of the new standard contained no more silver than 73 of the old, or 100 of the old were equivalent to 138 of the new. By this change the creditors of these more substantial debtors were obliged to submit to a loss, while the debtors acquired an exemption to the extent of about 27 per cent.

Lastly, Solon decreed that all those who had been condemned by the archons to “atimy” (civil disfranchisement) should be restored to their full privileges of citizens–excepting, however, from this indulgence those who had been condemned by the Ephetæ, or by the Areopagus, or by the Phylo-Basileis (the four kings of the tribes), after trial in the Prytaneum, on charges either of murder or treason. So wholesale a measure of amnesty affords strong grounds for believing that the previous judgments of the archons had been intolerably harsh; and it is to be recollected that the Draconian ordinances were then in force.

Such were the measures of relief with which Solon met the dangerous discontent then prevalent. That the wealthy men and leaders of the people–whose insolence and iniquity he has himself severely denounced in his poems, and whose views in nominating him he had greatly disappointed–should have detested propositions which robbed them without compensation of many legal rights, it is easy to imagine. But the statement of Plutarch that the poor emancipated debtors were also dissatisfied, from having expected that Solon would not only remit their debts, but also redivide the soil of Attica, seems utterly incredible; nor is it confirmed by any passage now remaining of the Solonian poems. Plutarch conceives the poor debtors as having in their minds the comparison with Lycurgus and the equality of property at Sparta, which, in my opinion, is clearly a matter of fiction; and even had it been true as a matter of history long past and antiquated, would not have been likely to work upon the minds of the multitude of Attica in the forcible way that the biographer supposes. The Seisachtheia must have exasperated the feelings and diminished the fortunes of many persons; but it gave to the large body of Thetes and small proprietors all that they could possibly have hoped. We are told that after a short interval it became eminently acceptable in the general public mind, and procured for Solon a great increase of popularity–all ranks concurring in a common sacrifice of thanksgiving and harmony. One incident there was which occasioned an outcry of indignation. Three rich friends of Solon, all men of great family in the state, and bearing names which appear in history as borne by their descendants–namely: Conon, Cleinias, and Hipponicus–having obtained from Solon some previous hint of his designs, profited by it, first to borrow money, and next to make purchases of lands; and this selfish breach of confidence would have disgraced Solon himself, had it not been found that he was personally a great loser, having lent money to the extent of five talents.

In regard to the whole measure of the Seisachtheia, indeed, though the poems of Solon were open to every one, ancient authors gave different statements both of its purport and of its extent. Most of them construed it as having cancelled indiscriminately all money contracts; while Androtion and others thought that it did nothing more than lower the rate of interest and depreciate the currency to the extent of 27 per cent., leaving the letter of the contracts unchanged. How Androtion came to maintain such an opinion we cannot easily understand. For the fragments now remaining from Solon seem distinctly to refute it, though, on the other hand, they do not go so far as to substantiate the full extent of the opposite view entertained by many writers–that all money contracts indiscriminately were rescinded–against which there is also a further reason, that if the fact had been so, Solon could have had no motive to debase the money standard. Such debasement supposes that there must have been “some” debtors at least whose contracts remained valid, and whom nevertheless he desired partially to assist. His poems distinctly mention three things:

- The removal of the mortgage-pillars.

- The enfranchisement of the land.

- The protection, liberation, and restoration of the persons of endangered or enslaved debtors.

All these expressions point distinctly to the Thetes and small proprietors, whose sufferings and peril were the most urgent, and whose case required a remedy immediate as well as complete. We find that his repudiation of debts was carried far enough to exonerate them, but no farther.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.