. . . he was now called upon to draw up a constitution and laws for the better working of the government in future. His constitutional changes were great and valuable: respecting his laws, what we hear is rather curious than important.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

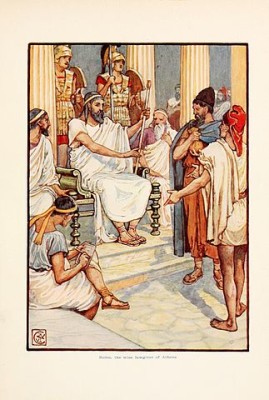

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Plutarch, treat the practice [interest on debt – JL] as a branch of the commercial and money-getting spirit which they are anxious to discourage; and one consequence of this was that they were, less disposed to contend strenuously for the inviolability of existing money-contracts. The conservative feeling on this point was stronger among the mass than among the philosophers. Plato even complains of it as inconveniently preponderant, and as arresting the legislator in all comprehensive projects of reform. For the most part, indeed, schemes of cancelling debts and redividing lands were never thought of except by men of desperate and selfish ambition, who made them stepping-stones to despotic power. Such men were denounced alike by the practical sense of the community and by the speculative thinkers: but when we turn to the case of the Spartan king, Agis III, who proposed a complete extinction of debts and an equal redivision of the landed property of the state, not with any selfish or personal views, but upon pure ideas of patriotism, well or ill understood, and for the purpose of renovating the lost ascendancy of Sparta–we find Plutarch expressing the most unqualified admiration of this young king and his projects, and treating the opposition made to him as originating in no better feelings than meanness and cupidity. The philosophical thinkers on politics conceived–and to a great degree justly, as I shall show hereafter–that the conditions of security, in the ancient world, imposed upon the citizens generally the absolute necessity of keeping up a military spirit and willingness to brave at all times personal hardship and discomfort: so that increase of wealth, on account of the habits of self-indulgence which it commonly introduces, was regarded by them with more or less of disfavor. If in their estimation any Grecian community had become corrupt, they were willing to sanction great interference with preëxisting rights for the purpose of bringing it back nearer to their ideal standard. And the real security for the maintenance of these rights lay in the conservative feelings of the citizens generally, much more than in the opinions which superior minds imbibed from the philosophers.

Such conservative feelings were in the subsequent Athenian democracy peculiarly deep-rooted. The mass of the Athenian people identified inseparably the maintenance of property in all its various shapes with that of their laws and constitution. And it is a remarkable fact, that though the admiration entertained at Athens for Solon was universal, the principle of his Seisachtheia and of his money-depreciation was not only never imitated, but found the strongest tacit reprobation; whereas at Rome, as well as in most of the kingdoms of modern Europe, we know that one debasement of the coin succeeded another. The temptation of thus partially eluding the pressure of financial embarrassments proved, after one successful trial, too strong to be resisted, and brought down the coin by successive depreciations from the full pound of twelve ounces to the standard of one half ounce. It is of some importance to take notice of this fact, when we reflect how much “Grecian faith” has been degraded by the Roman writers into a byword for duplicity in pecuniary dealings. The democracy of Athens–and indeed the cities of Greece generally, both oligarchies and democracies–stands far above the senate of Rome, and far above the modern kingdoms of France and England until comparatively recent times, in respect of honest dealing with the coinage. Moreover, while there occurred at Rome several political changes which brought about new tables, or at least a partial depreciation of contracts, no phenomenon of the same kind ever happened at Athens, during the three centuries between Solon and the end of the free working of the democracy, Doubtless there were fraudulent debtors at Athens; while the administration of private law, though not in any way conniving at their proceedings, was far too imperfect to repress them as effectually as might have been wished. But the public sentiment on the point was just and decided. It may be asserted with confidence that a loan of money at Athens was quite as secure as it ever was at any time or place of the ancient world–in spite of the great and important superiority of Rome with respect to the accumulation of a body of authoritative legal precedent, the source of what was ultimately shaped into the Roman jurisprudence. Among the various causes of sedition or mischief in the Grecian communities, we hear little of the pressure of private debt.

By the measures of relief above described, Solon had accomplished results surpassing his own best hopes. He had healed the prevailing discontents; and such was the confidence and gratitude which he had inspired, that he was now called upon to draw up a constitution and laws for the better working of the government in future. His constitutional changes were great and valuable: respecting his laws, what we hear is rather curious than important.

It has been already stated that, down to the time of Solon, the classification received in Attica was that of the four Ionic tribes, comprising in one scale the Phratries and Gentes, and in another scale the three Trittyes and forty-eight Naucraries–while the Eupatridæ, seemingly a few specially respected gentes, and perhaps a few distinguished families in all the gentes, had in their hands all the powers of government. Solon introduced a new principle of classification–called in Greek the “timocratic principle.” He distributed all the citizens of the tribes, without any reference to their gentes or phratries, into four classes, according to the amount of their property, which he caused to be assessed and entered in a public schedule. Those whose annual income was equal to five hundred medimni of corn (about seven hundred imperial bushels) and upward–one medimnus being considered equivalent to one drachma in money–he placed in the highest class; those who received between three hundred and five hundred medimni or drachmas formed the second class; and those between two hundred and three hundred, the third. The fourth and most numerous class comprised all those who did not possess land yielding a produce equal to two hundred medimni.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.