It had happened in several Grecian states that the governing oligarchies, either by quarrels among their own members or by the general bad condition of the people under their government, were deprived of that hold upon the public mind which was essential to their power.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

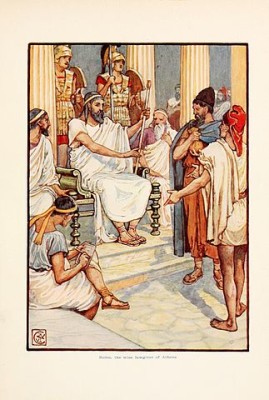

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The manifold and long-continued suffering of the poor under this system, plunged into a state of debasement not more tolerable than that of the Gallic “plebs”–and the injustices of the rich, in whom all political power was then vested–are facts well attested by the poems of Solon himself, even in the short fragments preserved to us. It appears that immediately preceding the time of his archonship the evils had ripened to such a point, and the determination of the mass of sufferers to extort for themselves some mode of relief had become so pronounced, that the existing laws could no longer be enforced. According to the profound remark of Aristotle–that seditions are generated by great causes but out of small incidents–we may conceive that some recent events had occurred as immediate stimulants to the outbreak of the debtors, like those which lent so striking an interest to the early Roman annals, as the inflaming sparks of violent popular movements for which the train had long before been laid. Condemnations by the archons of insolvent debtors may have been unusually numerous; or the maltreatment of some particular debtor, once a respected freeman, in his condition of slavery, may have been brought to act vividly upon the public sympathies; like the case of the old plebeian centurion at Rome–first impoverished by the plunder of the enemy, then reduced to borrow, and lastly adjudged to his creditor as an insolvent–who claimed the protection of the people in the forum, rousing their feelings to the highest pitch by the marks of the slave-whip visible on his person. Some such incidents had probably happened, though we have no historians to recount them. Moreover, it is not unreasonable to imagine that that public mental affliction which the purifier Epimenides had been invoked to appease, as it sprung in part from pestilence, so it had its cause partly in years of sterility, which must of course have aggravated the distress of the small cultivators. However this may be, such was the condition of things in B.C. 594 through mutiny of the poor freemen and “Thetes”, and uneasiness of the middling citizens, that the governing oligarchy, unable either to enforce their private debts or to maintain their political power, were obliged to invoke the well-known wisdom and integrity of Solon. Though his vigorous protest–which doubtless rendered him acceptable to the mass of the people–against the iniquity of the existing system had already been proclaimed in his poems, they still hoped that he would serve as an auxiliary to help them over their difficulties. They therefore chose him, nominally as archon along with Philombrotus, but with power in substance dictatorial.

It had happened in several Grecian states that the governing oligarchies, either by quarrels among their own members or by the general bad condition of the people under their government, were deprived of that hold upon the public mind which was essential to their power. Sometimes–as in the case of Pittacus of Mitylene anterior to the archonship of Solon, and often in the factions of the Italian republics in the middle ages–the collision of opposing forces had rendered society intolerable, and driven all parties to acquiesce in the choice of some reforming dictator. Usually, however, in the early Greek oligarchies, this ultimate crisis was anticipated by some ambitious individual, who availed himself of the public discontent to overthrow the oligarchy and usurp the powers of a despot. And so probably it might have happened in Athens, had not the recent failure of Cylon, with all its miserable consequences, operated as a deterring motive. It is curious to read, in the words of Solon himself, the temper in which his appointment was construed by a large portion of the community, but more especially by his own friends: bearing in mind that at this early day, so far as our knowledge goes, democratical government was a thing unknown in Greece–all Grecian governments were either oligarchical or despotic–the mass of the freemen having not yet tasted of constitutional privilege. His own friends and supporters were the first to urge him, while redressing the prevalent discontents, to multiply partisans for himself personally, and seize the supreme power. They even “chid him as a mad-man, for declining to haul up the net when the fish were already enmeshed.” The mass of the people, in despair with their lot, would gladly have seconded him in such an attempt; while many even among the oligarchy might have acquiesced in his personal government, from the mere apprehension of something worse if they resisted it. That Solon might easily have made himself despot admits of little doubt. And though the position of a Greek despot was always perilous, he would have had greater facility for maintaining himself in it than Pisistratus possessed after him; so that nothing but the combination of prudence and virtue, which marks his lofty character, restricted him within the trust specially confided to him. To the surprise of every one–to the dissatisfaction of his own friends–under the complaints alike (as he says) of various extreme and dissentient parties, who required him to adopt measures fatal to the peace of society–he set himself honestly to solve the very difficult and critical problem submitted to him.

Of all grievances, the most urgent was the condition of the poorer class of debtors. To their relief Solon’s first measure, the memorable “Seisachtheia”, or shaking off of burdens, was directed. The relief which it afforded was complete and immediate. It cancelled at once all those contracts in which the debtor had borrowed on the security either of his person or of his land: it forbade all future loans or contracts in which the person of the debtor was pledged as security; it deprived the creditor in future of all power to imprison, or enslave, or extort work, from his debtor, and confined him to an effective judgment at law authorizing the seizure of the property of the latter.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.