Never again do we hear of the law of debtor and creditor as disturbing Athenian tranquillity.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

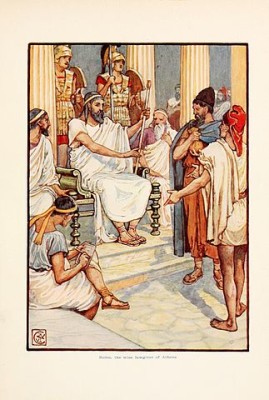

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It seems to have been the respect entertained for the character of Solon which partly occasioned these various misconceptions of his ordinances for the relief of debtors. Androtion in ancient, and some eminent critics in modern times are anxious to make out that he gave relief without loss or injustice to any one. But this opinion seems inadmissible. The loss to creditors by the wholesale abrogation of numerous preëxisting contracts, and by the partial depreciation of the coin, is a fact not to be disguised. The Seisachtheia of Solon, unjust so far as it rescinded previous agreements, but highly salutary in its consequences, is to be vindicated by showing that in no other way could the bonds of government have been held together, or the misery of the multitude alleviated. We are to consider,

- first, the great personal cruelty of these preëxisting contracts, which condemned the body of the free debtor and his family to slavery;

- next, the profound detestation created by such a system in the large mass of the poor, against both the judges and the creditors by whom it had been enforced, which rendered their feelings unmanageable so soon as they came together under the sentiment of a common danger and with the determination to insure to each other mutual protection.

Moreover, the law which vests a creditor with power over the person of his debtor so as to convert him into a slave, is likely to give rise to a class of loans which inspire nothing but abhorrence–money lent with the foreknowledge that the borrower will be unable to repay it, but also in the conviction that the value of his person as a slave will make good the loss; thus reducing him to a condition of extreme misery, for the purpose sometimes of aggrandizing, sometimes of enriching, the lender. Now the foundation on which the respect for contracts rests, under a good law of debtor and creditor, is the very reverse of this. It rests on the firm conviction that such contracts are advantageous to both parties as a class, and that to break up the confidence essential to their existence would produce extensive mischief throughout all society. The man whose reverence for the obligation of a contract is now the most profound, would have entertained a very different sentiment if he had witnessed the dealings of lender and borrower at Athens under the old ante-Solonian law. The oligarchy had tried their best to enforce this law of debtor and creditor with its disastrous series of contracts, and the only reason why they consented to invoke the aid of Solon was because they had lost the power of enforcing it any longer, in consequence of the newly awakened courage and combination of the people. That which they could not do for themselves, Solon could not have done for them, even had he been willing. Nor had he in his position the means either of exempting or compensating those creditors who, separately taken, were open to no reproach; indeed, in following his proceedings, we see plainly that he thought compensation due, not to the creditors, but to the past sufferings of the enslaved debtor, since he redeemed several of them from foreign captivity, and brought them back to their homes. It is certain that no measure simply and exclusively prospective would have sufficed for the emergency. There was an absolute necessity for overruling all that class of preëxisting rights which had produced so violent a social fever. While, therefore, to this extent, the Seisachtheia cannot be acquitted of injustice, we may confidently affirm that the injustice inflicted was an indispensable price paid for the maintenance of the peace of society, and for the final abrogation of a disastrous system as regarded insolvents. And the feeling as well as the legislation universal in the modern European world, by interdicting beforehand all contracts for selling a man’s person or that of his children into slavery, goes far to sanction practically the Solonian repudiation.

One thing is never to be forgotten in regard to this measure, combined with the concurrent amendments introduced by Solon in the law–it settled finally the question to which it referred. Never again do we hear of the law of debtor and creditor as disturbing Athenian tranquillity. The general sentiment which grew up at Athens, under the Solonian money-law and under the democratical government, was one of high respect for the sanctity of contracts. Not only was there never any demand in the Athenian democracy for new tables or a depreciation of the money standard, but a formal abnegation of any such projects was inserted in the solemn oath taken annually by the numerous Dicasts, who formed the popular judicial body called Heliæa or the Heliastic jurors: the same oath which pledged them to uphold the democratical constitution, also bound them to repudiate all proposals either for an abrogation of debts or for a redivision of the lands. There can be little doubt that under the Solonian law, which enabled the creditor to seize the property of his debtor, but gave him no power over the person, the system of money-lending assumed a more beneficial character. The old noxious contracts, mere snares for the liberty of a poor freeman and his children, disappeared, and loans of money took their place, founded on the property and prospective earnings of the debtor, which were in the main useful to both parties, and therefore maintained their place in the moral sentiment of the public. And though Solon had found himself compelled to rescind all the mortgages on land subsisting in his time, we see money freely lent upon this same security throughout the historical times of Athens, and the evidentiary mortgage-pillars remaining ever after undisturbed.

In the sentiment of an early society, as in the old Roman law, a distinction is commonly made between the principal and the interest of a loan, though the creditors have sought to blend them indissolubly together.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.