Such are the only new political institutions (apart from the laws to be noticed presently) which there are grounds for ascribing to Solon, when we take proper care to discriminate what really belongs to Solon and his age from the Athenian constitution as afterward remodeled.

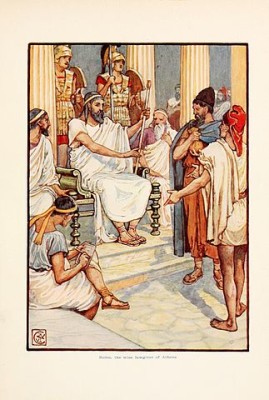

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Had the public assembly been called upon to act alone without aid or guidance, this accountability would have proved only nominal. But Solon converted it into a reality by another new institution, which will hereafter be found of great moment in the working out of the Athenian democracy. He created the pro-bouleutic, or pre-considering senate, with intimate and especial reference to the public assembly–to prepare matters for its discussion, to convoke and superintend its meetings, and to insure the execution of its decrees. The senate, as first constituted by Solon, comprised four hundred members, taken in equal proportions from the four tribes; not chosen by lot, as they will be found to be in the more advanced stage of the democracy, but elected by the people, in the same way as the archons then were–persons of the fourth, or poorest class of the census, though contributing to elect, not being themselves eligible.

But while Solon thus created the new pre-considering senate, identified with and subsidiary to the popular assembly, he manifested no jealousy of the preexisting Areopagitic senate. On the contrary, he enlarged its powers, gave to it an ample supervision over the execution of the laws generally, and imposed upon it the censorial duty of inspecting the lives and occupation of the citizens, as well as of punishing men of idle and dissolute habits. He was himself, as past archon, a member of this ancient senate, and he is said to have contemplated that by means of the two senates the state would be held fast, as it were with a double anchor, against all shocks and storms.

Such are the only new political institutions (apart from the laws to be noticed presently) which there are grounds for ascribing to Solon, when we take proper care to discriminate what really belongs to Solon and his age from the Athenian constitution as afterward remodeled. It has been a practice common with many able expositors of Grecian affairs, and followed partly even by Dr. Thirlwall, to connect the name of Solon with the whole political and judicial state of Athens as it stood between the age of Pericles and that of Demosthenes–the regulations of the senate of five hundred, the numerous public dicasts or jurors taken by lot from the people–as well as the body annually selected for law-revision, and called “nomothets”–and the open prosecution (called the “graphe paranomon”) to be instituted against the proposer of any measure illegal, unconstitutional, or dangerous. There is indeed some countenance for this confusion between Solonian and post-Solonian Athens, in the usage of the orators themselves. For Demosthenes and Æschines employ the name of Solon in a very loose manner, and treat him as the author of institutions belonging evidently to a later age–for example: the striking and characteristic oath of the Heliastic jurors, which Demosthenes ascribes to Solon, proclaims itself in many ways as belonging to the age after Clisthenes, especially by the mention of the senate of five hundred, and not of four hundred. Among the citizens who served as jurors or dicasts, Solon was venerated generally as the author of the Athenian laws. An orator, therefore, might well employ his name for the purpose of emphasis, without provoking any critical inquiry whether the particular institution, which he happened to be then impressing upon his audience, belonged really to Solon himself or to the subsequent periods. Many of those institutions, which Dr. Thirlwall mentions in conjunction with the name of Solon, are among the last refinements and elaborations of the democratical mind of Athens–gradually prepared, doubtless, during the interval between Clisthenes and Pericles, but not brought into full operation until the period of the latter (B.C. 460-429). For it is hardly possible to conceive these numerous dicasteries and assemblies in regular, frequent, and long-standing operation, without an assured payment to the dicasts who composed them. Now such payment first began to be made about the time of Pericles, if not by his actual proposition; and Demosthenes had good reason for contending that if it were suspended, the judicial as well as the administrative system of Athens would at once fall to pieces. It would be a marvel, such as nothing short of strong direct evidence would justify us in believing, that in an age when even partial democracy was yet untried, Solon should conceive the idea of such institutions; it would be a marvel still greater, that the half-emancipated Thetes and small proprietors, for whom he legislated–yet trembling under the rod of the Eupatrid archons, and utterly inexperienced in collective business–should have been found suddenly competent to fulfil these ascendant functions, such as the citizens of conquering Athens in the days of Pericles, full of the sentiment of force and actively identifying themselves with the dignity of their community, became gradually competent, and not more than competent, to exercise with effect. To suppose that Solon contemplated and provided for the periodical revision of his laws by establishing a nomothetic jury or dicastery, such as that which we find in operation during the time of Demosthenes, would be at variance (in my judgment) with any reasonable estimate either of the man or of the age. Herodotus says that Solon, having exacted from the Athenians solemn oaths that “they” would not rescind any of his laws for ten years, quitted Athens for that period, in order that he might not be compelled to rescind them himself. Plutarch informs us that he gave to his laws force for a century. Solon himself, and Draco before him, had been lawgivers evoked and empowered by the special emergency of the times: the idea of a frequent revision of laws, by a body of lot-selected dicasts, belongs to a far more advanced age, and could not well have been present to the minds of either. The wooden rollers of Solon, like the tables of the Roman decemvìrs, were doubtless intended as a permanent “”fons omnis publici privatique juris””.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.