Such were the divisions in the political scale established by Solon, called by Aristotle a “timocracy”, in which the rights, honors, functions, and liabilities of the citizens were measured out according to the assessed property of each.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

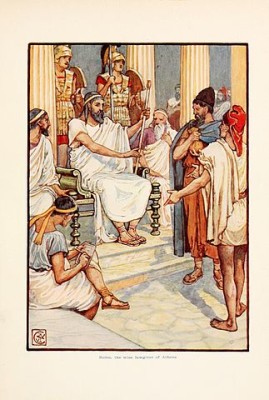

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The first class, called Pentacosiomedimni, were alone eligible to the archonship and to all commands: the second were called the knights or horsemen of the state, as possessing enough to enable them to keep a horse and perform military service in that capacity: the third class, called the [Greek: Zeugitæ], formed the heavy-armed infantry, and were bound to serve, each with his full panoply. Each of these three classes was entered in the public schedule as possessed of a taxable capital calculated with a certain reference to his annual income, but in a proportion diminishing according to the scale of that income–and a man paid taxes to the state according to the sum for which he stood rated in the schedule; so that this direct taxation acted really like a graduated income-tax. The ratable property of the citizen belonging to the richest class (the Pentacosiomedimnus) was calculated and entered on the state schedule at a sum of capital equal to twelve times his annual income; that of the Hippeus, horseman or knight, at a sum equal to ten times his annual income: that of the Zeugite, at a sum equal to five times his annual income. Thus a Pentacosiomedimnus, whose income was exactly 500 drachmas (the minimum qualification of his class), stood rated in the schedule for a taxable property of 6,000 drachmas or one talent, being twelve times his income–if his annual income were 1,000 drachmas, he would stand rated for 12,000 drachmas or two talents, being the same proportion of income to ratable capital. But when we pass to the second class, horsemen or knights, the proportion of the two is changed. The horseman possessing an income of just 300 drachmas (or 300 medimni) would stand rated for 3,000 drachmas, or ten times his real income, and so in the same proportion for any income above 300 and below 500. Again, in the third class, or below 300, the proportion is a second time altered–the Zeugite possessing exactly 200 drachmas of income was rated upon a still lower calculation, at 1,000 drachmas, or a sum equal to five times his income; and all incomes of this class (between 200 and 300 drachmas) would in like manner be multiplied by five in order to obtain the amount of ratable capital. Upon these respective sums of schedule capital all direct taxation was levied. If the state required 1 percent of direct tax, the poorest Pentacosiomedimnus would pay (upon 6,000 drachmas) 60 drachmas; the poorest Hippeus would pay (upon 3,000 drachmas) 30; the poorest Zeugite would pay (upon 1,000 drachmas) 10 drachmas. And thus this mode of assessment would operate like a “graduated” income-tax, looking at it in reference to the three different classes–but as an “equal” income-tax, looking at it in reference to the different individuals comprised in one and the same class.

All persons in the state whose annual income amounted to less than two hundred medimni or drachmas were placed in the fourth class, and they must have constituted the large majority of the community. They were not liable to any direct taxation, and perhaps were not at first even entered upon the taxable schedule, more especially as we do not know that any taxes were actually levied upon this schedule during the Solonian times. It is said that they were all called Thetes, but this appellation is not well sustained, and cannot be admitted: the fourth compartment in the descending scale was indeed termed the Thetic census, because it contained all the Thetes, and because most of its members were of that humble description; but it is not conceivable that a proprietor whose land yielded to him a clear annual return of 100, 120, 140, or 180 drachmas, could ever have been designated by that name.

Such were the divisions in the political scale established by Solon, called by Aristotle a “timocracy”, in which the rights, honors, functions, and liabilities of the citizens were measured out according to the assessed property of each. The highest honors of the state–that is, the places of the nine archons annually chosen, as well as those in the senate of Areopagus, into which the past archons always entered (perhaps also the posts of Prytanes of the Naukrari) were reserved for the first class: the poor Eupatrids became ineligible, while rich men, not Eupatrids, were admitted. Other posts of inferior distinction were filled by the second and third classes, who were, moreover, bound to military service–the one on horseback, the other as heavy-armed soldiers on foot. Moreover, the “liturgies” of the state, as they were called–unpaid functions such as the trierarchy, choregy, gymnasiarchy, etc., which entailed expense and trouble on the holder of them–were distributed in some way or other between the members of the three classes, though we do not know how the distribution was made in these early times. On the other hand, the members of the fourth or lowest class were disqualified from holding any individual office of dignity. They performed no liturgies, served in case of war only as light-armed or with a panoply provided by the state, and paid nothing to the direct property-tax or Eisphora. It would be incorrect to say that they paid “no” taxes, for indirect taxes, such as duties on imports, fell upon them in common with the rest; and we must recollect that these latter were, throughout a long period of Athenian history, in steady operation, while the direct taxes were only levied on rare occasions.

But though this fourth class, constituting the great numerical majority of the free people, were shut out from individual office, their collective importance was in another way greatly increased. They were invested with the right of choosing the annual archons, out of the class of Pentacosiomedimni; and what was of more importance still, the archons and the magistrates generally, after their year of office, instead of being accountable to the senate of Areopagus, were made formally accountable to the public assembly sitting in judgment upon their past conduct. They might be impeached and called upon to defend themselves, punished in case of misbehavior, and debarred from the usual honor of a seat in the senate of Areopagus.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |