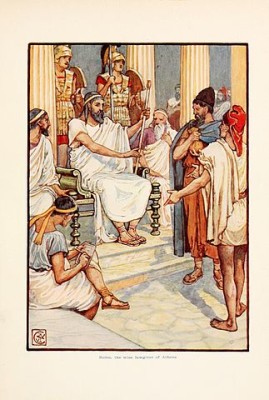

This series has eighteen easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Solon the Legislator.

Introduction

This begins a very lengthy series of Solon, his laws and his career. The significance of Solon’s laws beyond that of the lawyers and legal history is what they reveal about daily life in the ancient world. In terms of legal history, Solon’s laws formed the basis of the legal system of western civilization and, due to Europe’s influence in the modern era, much of the rest of the world, too. The character of his legislation and its influence upon the course of history have been set forth by many authors. The following account is perhaps the best that has appeared in modern literature.

This selection is from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

George Grote was for a very long time the leading authority in the world on Ancient Greece.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Solon, son of Execestides, was a Eupatrid of middling fortune, but of the purest heroic blood, belonging to the gens or family of the Codrids and Neleids, and tracing his origin to the god Poseidon. His father is said to have diminished his substance by prodigality, which compelled Solon in his earlier years to have recourse to trade, and in this pursuit he visited many parts of Greece and Asia. He was thus enabled to enlarge the sphere of his observation, and to provide material for thought as well as for composition. His poetical talents displayed themselves at a very early age, first on light, afterward on serious subjects. It will be recollected that there was at that time no Greek prose writing, and that the acquisitions as well as the effusions of an intellectual man, even in their simplest form, adjusted themselves not to the limitations of the period and the semicolon, but to those of the hexameter and pentameter. Nor, in point of fact, do the verses of Solon aspire to any higher effect than we are accustomed to associate with an earnest, touching, and admonitory prose composition. The advice and appeals which he frequently addressed to his countrymen were delivered in this easy metre, doubtless far less difficult than the elaborate prose of subsequent writers or speakers, such as Thucydides, Isocrates, or Demosthenes. His poetry and his reputation became known throughout many parts of Greece, so that he was classed along with Thales of Miletus, Bias of Priene, Pittacus of Mitylene, Periander of Corinth, Cleobulus of Lindus, Cheilon of Lacedaemon — altogether forming the constellation afterward renowned as the seven wise men.

The first particular event in respect to which Solon appears as an active politician, is the possession of the island of Salamis, then disputed between Megara and Athens. Megara was at that time able to contest with Athens, and for some time to contest with success, the occupation of this important island — a remarkable fact, which perhaps may be explained by supposing that the inhabitants of Athens and its neighborhood carried on the struggle with only partial aid from the rest of Attica. However this may be, it appears that the Megarians had actually established themselves in Salamis, at the time when Solon began his political career, and that the Athenians had experienced so much loss in the struggle as to have formally prohibited any citizen from ever submitting a proposition for its reconquest. Stung with this dishonorable abnegation, Solon counterfeited a state of ecstatic excitement, rushed into the agora, and there on the stone usually occupied by the official herald, pronounced to the surrounding crowd a short elegiac poem which he had previously composed on the subject of Salamis. Enforcing upon them the disgrace of abandoning the island, he wrought so powerfully upon their feelings that they rescinded the prohibitory law. “Rather (he exclaimed) would I forfeit my native city and become a citizen of Pholegandrus, than be still named an Athenian, branded with the shame of surrendered Salamis!” The Athenians again entered into the war, and conferred upon him the command of it–partly, as we are told, at the instigation of Pisistratus, though the latter must have been at this time (B.C. 600-594) a very young man, or rather a boy.

The stories in Plutarch, as to the way in which Salamis was recovered, are contradictory as well as apocryphal, ascribing to Solon various stratagems to deceive the Megarian occupiers. Unfortunately no authority is given for any of them. According to that which seems the most plausible, he was directed by the Delphian god first to propitiate the local heroes of the island; and he accordingly crossed over to it by night, for the purpose of sacrificing to the heroes Periphemus and Cychreus on the Salaminian shore. Five hundred Athenian volunteers were then levied for the attack of the island, under the stipulation that if they were victorious they should hold it in property and citizenship. They were safely landed on an outlying promontory, while Solon, having been fortunate enough to seize a ship which the Megarians had sent to watch the proceedings, manned it with Athenians and sailed straight toward the city of Salamis, to which the Athenians who had landed also directed their march. The Megarians marched out from the city to repel the latter, and during the heat of the engagement Solon, with his Megarian ship and Athenian crew, sailed directly to the city. The Megarians, interpreting this as the return of their own crew, permitted the ship to approach without resistance, and the city was thus taken by surprise. Permission having been given to the Megarians to quit the island, Solon took possession of it for the Athenians, erecting a temple to Enyalius, the god of war, on Cape Sciradium, near the city of Salamis.

The citizens of Megara, however, made various efforts for the recovery of so valuable a possession, so that a war ensued long as well as disastrous to both parties. At last it was agreed between them to refer the dispute to the arbitration of Sparta, and five Spartans were appointed to decide it–Critolaidas, Amompharetus, Hypsechidas, Anaxilas, and Cleomenes.

| Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.