It is on the occasion of Solon’s legislation that we obtain our first glimpse–unfortunately but a glimpse–of the actual state of Attica and its inhabitants. It is a sad and repulsive picture, presenting to us political discord and private suffering combined.

Continuing Solon’s Early Greek Legislation,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eighteen easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Solon’s Early Greek Legislation.

Time: 594 BC

Place: Athens

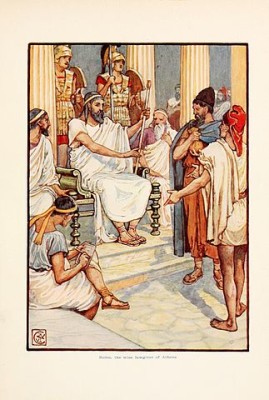

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The verdict in favor of Athens was founded on evidence which it is somewhat curious to trace. Both parties attempted to show that the dead bodies buried in the island conformed to their own peculiar mode of interment, and both parties are said to have cited verses from the catalogue of the _Iliad_–each accusing the other of error or interpolation. But the Athenians had the advantage on two points: first, there were oracles from Delphi, wherein Salamis was mentioned with the epithet Ionian; next Philæus and Eurysaces, sons of the Telamonian Ajax, the great hero of the island, had accepted the citizenship of Athens, made over Salamis to the Athenians, and transferred their own residences to Brauron and Melite in Attica, where the “deme”, or “gens”, Philaidæ still worshipped Philæus as its eponymous ancestor. Such a title was held sufficient, and Salamis was adjudged by the five Spartans to Attica, with which it ever afterward remained incorporated until the days of Macedonian supremacy. Two centuries and a half later, when the orator Æschines argued the Athenian right to Amphipolis against Philip of Macedon, the legendary elements of the title were indeed put forward, but more in the way of preface or introduction to the substantial political grounds. But in the year 600 B.C. the authority of the legend was more deep-seated and operative, and adequate by itself to determine a favorable verdict.

In addition to the conquest of Salamis, Solon increased his reputation by espousing the cause of the Delphian temple against the extortionate proceedings of the inhabitants of Cirrha, and the favor of the oracle was probably not without its effect in procuring for him that encouraging prophecy with which his legislative career opened.

It is on the occasion of Solon’s legislation that we obtain our first glimpse–unfortunately but a glimpse–of the actual state of Attica and its inhabitants. It is a sad and repulsive picture, presenting to us political discord and private suffering combined.

Violent dissensions prevailed among the inhabitants of Attica, who were separated into three factions–the Pedieis, or men of the plain, comprising Athens, Eleusis, and the neighboring territory, among whom the greatest number of rich families were included; the mountaineers in the east and north of Attica, called Diacrii, who were, on the whole, the poorest party; and the Paralii in the southern portion of Attica from sea to sea, whose means and social position were intermediate between the two. Upon what particular points these intestine disputes turned we are not distinctly informed. They were not, however, peculiar to the period immediately preceding the archonship of Solon. They had prevailed before, and they reappear afterward prior to the despotism of Pisistratus; the latter standing forward as the leader of the Diacrii, and as champion, real or pretended, of the poorer population.

But in the time of Solon these intestine quarrels were aggravated by something much more difficult to deal with–a general mutiny of the poorer population against the rich, resulting from misery combined with oppression. The Thetes, whose condition we have already contemplated in the poems of Homer and Hesiod, are now presented to us as forming the bulk of the population of Attica–the cultivating tenants, metayers, and small proprietors of the country. They are exhibited as weighed down by debts and dependence, and driven in large numbers out of a state of freedom into slavery–the whole mass of them (we are told) being in debt to the rich, who were proprietors of the greater part of the soil. They had either borrowed money for their own necessities, or they tilled the lands of the rich as dependent tenants, paying a stipulated portion of the produce, and in this capacity they were largely in arrear.

All the calamitous effects were here seen of the old harsh law of debtor and creditor–once prevalent in Greece, Italy, Asia, and a large portion of the world–combined with the recognition of slavery as a legitimate status, and of the right of one man to sell himself as well as that of another man to buy him. Every debtor unable to fulfil his contract was liable to be adjudged as the slave of his creditor, until he could find means either of paying it or working it out; and not only he himself, but his minor sons and unmarried daughters and sisters also, whom the law gave him the power of selling. The poor man thus borrowed upon the security of his body (to translate literally the Greek phrase) and upon that of the persons in his family. So severely had these oppressive contracts been enforced, that many debtors had been reduced from freedom to slavery in Attica itself, many others had been sold for exportation, and some had only hitherto preserved their own freedom by selling their children. Moreover, a great number of the smaller properties in Attica were under mortgage, signified–according to the formality usual in the Attic law, and continued down throughout the historical times–by a stone pillar erected on the land, inscribed with the name of the lender and the amount of the loan. The proprietors of these mortgaged lands, in case of an unfavorable turn of events, had no other prospect except that of irremediable slavery for themselves and their families, either in their own native country robbed of all its delights, or in some barbarian region where the Attic accent would never meet their ears. Some had fled the country to escape legal adjudication of their persons, and earned a miserable subsistence in foreign parts by degrading occupations. Upon several, too, this deplorable lot had fallen by unjust condemnation and corrupt judges; the conduct of the rich, in regard to money sacred and profane, in regard to matters public as well as private, being thoroughly unprincipled and rapacious.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.