Moreover, it was known everywhere among the Gauls that Cæsar had only one more summer to hold his command, and that after that time they would have nothing more to fear.

Continuing Caesar Conquers Gaul,

our selection from History of Julius Caesar by Napoleon III published in 1865. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Caesar Conquers Gaul.

Time: September 52 BC

Place: Alesia, Gaul (France)

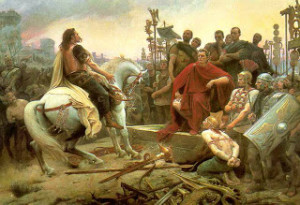

Public Domain Image from Wikipedia.

During the night of the following day Fabius again sent his cavalry forward with orders to delay the march of the enemy so as to give time for the arrival of the infantry. The two bodies of cavalry were soon engaged, but the enemy, thinking he had to contend with only the same troops as the day before, drew up his infantry in line so as to support the squadrons, when suddenly the Roman legions appeared in order of battle. At this sight the barbarians were struck with terror, the long train of baggage thrown into confusion, and the infantry dispersed. More than twelve thousand men were killed and all the baggage fell into the hands of the Romans.

Only five thousand fugitives escaped from this rout; they were received by the Senonan, Drappes, the same who in the first revolt of the Gauls had collected a crowd of vagabonds, slaves, exiles, and robbers to intercept the convoys of the Romans.

They took the direction of the Narbonnese with the Cadurcan Lucterius who had before attempted a similar invasion.

Rebilus pursued them with two legions in order to avoid the shame of seeing the province suffering any injury from such a contemptible rabble. As for Fabius, he led the twenty-five cohorts against the Carnutes and the other tribes whose forces had already been reduced by the defeat they had suffered from Dumnacus. The Carnutes, though often beaten, had never been completely subdued. They gave hostages, and the Armoricans followed their example. Dumnacus, driven out of his own territory, went to seek a refuge in the remotest part of Gaul.

Drappes and Lucterius, when they learned that they were pursued by Rebilus and his two legions, gave up the design of penetrating into the province; they halted in the country of the Cadurci and threw themselves into the oppidum of Uxellodunum (Puy-d’Issolu, near Varac), an exceedingly strong place formerly under the dependence of Lucterius, who soon incited the inhabitants to revolt.

Rebilus appeared immediately before the town, which, surrounded on all sides by steep rocks, was, even without being defended, difficult of access to armed men. Knowing that there was in the oppidum so great a quantity of baggage that the besieged could not send it away secretly without being detected and overtaken by the cavalry, and even by the infantry, he divided his cohorts into three bodies and established three camps on the highest points. Next he ordered a countervallation to be made. On seeing these preparations the besieged remembered the ill-fortune of Alesia, and feared a similar fate. Lucterius, who had witnessed the horrors of famine during the investment of that town, now took especial care of the provisions.

During this time the garrison of the oppidum attacked the redoubts of Rebilus several times, which obliged him to interrupt the work of the countervallation, which, indeed, he had not sufficient forces to defend.

Drappes and Lucterius established themselves at a distance of ten miles from the oppidum, with the intention of introducing the provisions gradually. They shared the duties between them. Drappes remained with part of the troops to protect the camp. Lucterius, during the night-time, endeavored to introduce beasts of burden into the town by a narrow and wooded path. The noise of their march gave warning to the sentries. Rebilus, informed of what was going on, ordered the cohorts to sally from the neighboring redoubts, and at daybreak fell upon the convoy, the escort of which was slaughtered. Lucterius, having escaped with a small number of his followers, was unable to rejoin Drappes.

Rebilus soon learned from prisoners that the rest of the troops which had left the oppidum were with Drappes at a distance of twelve miles, and that by a fortunate chance not one fugitive had taken that direction to carry him news of the last combat. The Roman general sent in advance all the cavalry and the light German infantry; he followed them with one legion, without baggage, leaving the other as a guard to the three camps. When he came near the enemy he learned, by his scouts, that the barbarians–according to their custom of neglecting the heights–had placed their camp on the banks of a river (probably the Dordogne); that the Germans and the cavalry had surprised them, and that they were already fighting. Rebilus then advanced rapidly at the head of the legion drawn up in order of battle and took possession of the heights.

As soon as the ensigns appeared, the cavalry redoubled its ardor; the cohorts rushed forward from all sides and the Gauls were taken or killed. The booty was immense and Drappes fell into the hands of the Romans.

Rebilus, after this successful exploit, which cost him but a few wounded, returned under the walls of Uxellodunum. Fearing no longer any attack from without, he set resolutely to work to continue his circumvallation. The day after, C. Fabius arrived, followed by his troops, and shared with him the labors of the siege. While the south of

Gaul was the scene of serious trouble, Cæsar left the quaestor, Mark Antony, with fifteen cohorts in the country of the Bellovaci. To deprive the Belgæ of all idea of revolt he had proceeded to the neighboring countries with two legions; had exacted hostages, and restored confidence by his conciliating speeches. When he arrived among the Carnutes–who the year before had been the first to revolt–he saw that the remembrance of their conduct kept them in great alarm, and he resolved to put an end to it by causing his vengeance to fall only upon Gutruatus, the instigator of the war.

This man was brought in and delivered up. Although Cæsar was naturally inclined to be indulgent, he could not resist the tumultuous entreaties of his soldiers, who made that chief responsible for all the dangers they had run and for all the misery they had suffered. Gutruatus died under the stripes and was afterward beheaded.

It was in the land of the Carnutes that Cæsar received news, by the letters of Rebilus, of the events which had taken place at Uxellodunum and of the resistance of the besieged. Although a handful of men shut up in a fortress was not very formidable, he judged it necessary to punish their obstinacy, for fear that the Gauls should entertain the conviction that it was not strength, but constancy, which had failed them in resisting the Romans; and lest this example might encourage the other states which possessed fortresses advantageously situated, to recover their independence.

Moreover, it was known everywhere among the Gauls that Cæsar had only one more summer to hold his command, and that after that time they would have nothing more to fear. He left therefore the lieutenant Quintus Calenus at the head of his two legions, with orders to follow him by ordinary marches, and, with his cavalry, hastened by long marches toward Uxellodunum. Cæsar, arriving unexpectedly before the town, found it completely defended at all accessible points. He judged that it could not be taken by assault (neque ab oppugnatione recedi vidaret ullaconditione posse), and, as it was abundantly provided with provisions, conceived the project of depriving the inhabitants of water.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.