Day after day was passing in this manner when Caesar was informed of the arrival of C. Trebonius and his troops, which raised the number of his legions to seven.

Continuing Caesar Conquers Gaul,

our selection from History of Julius Caesar by Napoleon III published in 1865. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Caesar Conquers Gaul.

Time: September 52 BC

Place: Alesia, Gaul (France)

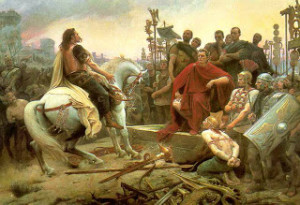

Public Domain Image from Wikipedia.

Nevertheless, in one of the skirmishes which were continually taking place within sight of the two camps about the fordable places of the marsh, the German infantry–which Caesar had sent for from beyond the Rhine in order to mix them with the cavalry–joined in a body, boldly crossed the marsh, and, meeting with little resistance, continued the pursuit with such impetuosity that fear seized not only the enemy who fought, but even those who were in reserve. Instead of availing themselves of the advantages of the ground, all fled in a cowardly manner. They did not stop until they were within their camp, and some even were not ashamed to fly beyond it. This defeat caused a general discouragement, for the Gauls were as easily daunted by the least reverse as they were made arrogant by the smallest success.

Day after day was passing in this manner when Caesar was informed of the arrival of C. Trebonius and his troops, which raised the number of his legions to seven. The chiefs of the Bellovaci then feared an investment like that of Alesia, and resolved to quit their position. They sent away by night the old men, the infirm, the unarmed men, and the part of the baggage which they had kept with them. Scarcely was this confused multitude in motion–embarrassed by its own mass and its numerous chariots–when daylight surprised it, and the troops had to be drawn up in line before the camp to give the column time to move away. Caesar saw no advantage either in giving battle to those who were in position, nor, on account of the steepness of the hill, in pursuing those who were making their retreat; he resolved, nevertheless, to make two legions advance in order to disturb the enemy in its retreat. Having observed that the mountain on which the Gauls were established was connected with another height (Mont Collet), from which it was only separated by a narrow valley, he ordered bridges to be thrown across the marsh. The legions crossed over them and soon attained the summit of the height, which was defended on both sides by abrupt declivities.

There he collected his troops and advanced in order of battle up to the extremity of the plateau, whence the engines placed in battery could reach the masses of the enemy with their missiles.

The barbarians, rendered confident by the advantage of their position, were ready to accept battle if the Romans dared to attack the mountain; besides, they were afraid to withdraw their troops successively, as, if divided, they might have been thrown into disorder. This attitude led Cæsar to resolve upon leaving twenty cohorts under arms, and on tracing a camp on this spot and retrenching it. When the works were completed the legions were placed before the retrenchments and the cavalry distributed with their horses bridled at the outposts. The Bellovaci had recourse to a stratagem in order to effect their retreat. They passed from hand to hand the fascines and the straw on which, according to the Gaulish custom, they were in the habit of sitting, preserving at the same time their order of battle; placed them in front of the camp, and toward the close of the day, on a preconcerted signal, set fire to them. Immediately a vast flame concealed from the Romans the Gaulish troops, who fled in haste.

Although the fire prevented Cæsar from seeing the retreat of the enemy he suspected it. He ordered his legions to advance, and sent the cavalry in pursuit, but he marched slowly in fear of some stratagem, suspecting the barbarians to have formed the design of drawing the Romans to disadvantageous ground. Besides, the cavalry did not dare to ride through the smoke and flames; and thus the Bellovaci were able to pass over a distance of ten miles and halt in a place strongly fortified by nature (Mont Ganelon), where they pitched their camp. In this position they confined themselves to placing cavalry and infantry in frequent ambuscades, thus inflicting great damage on the Romans when they went to forage. After several encounters of this kind Cæsar learned by a prisoner that Correus, chief of the Bellovaci, with six thousand picked infantry and one thousand horsemen, was preparing an ambuscade in places where the abundance of corn and forage was likely to attract the Romans. In consequence of this information he sent forward the cavalry, which was always employed to protect the foragers, and joined with them some light-armed auxiliaries, while he himself, with a greater number of legions, followed them as closely as possible.

The enemy had posted themselves in a plain–that of Choisy-au-Bac–of about one thousand paces in length and the same in breadth, surrounded on one side by forests, on the other by a river which was difficult to pass (the Aisne). The cavalry becoming acquainted with the designs of the Gauls and feeling themselves supported, advanced resolutely in squadrons toward this plain, which was surrounded with ambushes on all sides.

Correus, seeing them arrive in this manner, believed the opportunity favorable for the execution of his plan and began by attacking the first squadrons with a few men. The Romans sustained the shock without concentrating themselves in a mass on the same point, “which,” says Hirtius, “usually happens in cavalry engagements, and leads always to a dangerous confusion.” There, on the contrary, the squadrons, remaining separated, fought in detached bodies, and when one of them advanced, its flanks were protected by the others. Correus then ordered the rest of his cavalry to issue from the woods. An obstinate combat began on all sides without any decisive result until the enemy’s infantry, debouching from the forest in close ranks, forced the Roman cavalry to fall back. The lightly armed soldiers who preceded the legions placed themselves between the squadrons and restored the fortune of the combat. After a certain time the troops, animated by the approach of the legions and the arrival of Caesar, and ambitious of obtaining alone the honor of the victory, redoubled their efforts and gained the advantage. The enemy, on the other hand, were discouraged and took to flight, but were stopped by the very obstacles which they intended to throw in the way of the Romans. A small number, nevertheless, escaped through the forest and crossed the river. Correus, who remained unshaken under this catastrophe, obstinately refused to surrender, and fell pierced with wounds. After this success Caesar hoped that if he continued his march the enemy in dismay would abandon his camp, which was only eight miles from the field of battle. He therefore crossed the Aisne, though not without great difficulties.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.