He had with him the Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth legions, composed of old soldiers of tried valor, and the Eleventh, which, formed of picked young men who had gone through eight campaigns, deserved his confidence, although it could not be compared with the others with regard to bravery and experience in war.

Continuing Caesar Conquers Gaul,

our selection from History of Julius Caesar by Napoleon III published in 1865. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Caesar Conquers Gaul.

Time: September 52 BC

Place: Alesia, Gaul (France)

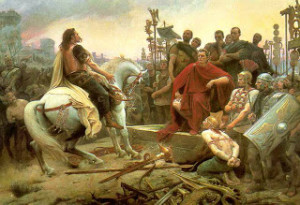

Public Domain Image from Wikipedia.

When this army was assembled he marched against the Bellovaci, established his camp on their territory, and sent cavalry in every direction in order to make some prisoners and learn from them the designs of the enemy. The cavalry reported that the emigration was general, and that the few inhabitants who were to be seen were not remaining behind in order to apply themselves to agriculture, but to act as spies upon the Romans.

Caesar by interrogating the prisoners learned that all the Bellovaci able to fight had assembled on one spot, and that they had been joined by the Ambiani, the Aulerci, the Caletes, the Veliocasses, and the Atrebates. Their camp was in a forest on a height surrounded by marshes–Mont Saint Marc, in the forest of Compiègne; their baggage had been transported to more distant woods. The command was divided among several chiefs, but the greater part obeyed Correus on account of his well-known hatred of the Romans. Commius had a few days before gone to seek succor from the numerous Germans who lived in great numbers in the neighboring counties–probably those on the banks of the Meuse.

The Bellovaci resolved with one accord to give Caesar battle, if, as report said, he was advancing with only three legions; for they wouldn’t run the risk of having afterward to encounter his entire army. If, on the contrary, the Romans were advancing with more considerable forces they proposed to keep their positions and confine themselves to intercepting, by means of ambuscades, the provisions and forage, which were very scarce at that season.

This plan, confirmed by many reports, seemed to Caesar full of prudence and altogether contrary to the usual rashness of the barbarians. He took therefore every possible care to dissimulate as to the number of his troops. He had with him the Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth legions, composed of old soldiers of tried valor, and the Eleventh, which, formed of picked young men who had gone through eight campaigns, deserved his confidence, although it could not be compared with the others with regard to bravery and experience in war. In order to deceive the enemy by showing them only three legions–the only number they were willing to fight–he placed the Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth in one line; while the baggage, which was not very considerable, was placed behind under the protection of the Eleventh legion, which closed the march. In this order, which formed almost a square, he came unawares in sight of the Bellovaci. At the unexpected view of the legions, which advanced in order of battle and with a firm step, they lost their courage and, instead of attacking, as they had engaged to do, they confined themselves to drawing themselves up before their camp without leaving the height. A valley deeper than it was wide separated the two armies.

On account of this obstacle and the numerical superiority of the barbarians, Caesar, though he had wished for battle, abandoned the idea of attacking them and placed his camp opposite that of the Gauls in a strong position. He caused it to be surrounded with a parapet twelve feet high, surmounted by accessory works proportioned to the importance of the retrenchment and preceded by a double fosse fifteen feet wide, with a square bottom. Towers of three stories were constructed from distance to distance and united together by covered bridges, the exterior parts of which were protected by hurdle-work. In this manner the camp was protected not only by a double fosse, but also by a double row of defenders, some of whom, placed on the bridges, could from this elevated and sheltered position throw their missiles farther and with a better aim; while the others, placed on the vallum, nearer to the enemy, were protected by the bridges from the missiles which showered down upon them. The entrances were defended by means of higher towers and were closed with gates.

These formidable retrenchments had a double aim–to increase the confidence of the barbarians by making them believe that they were feared, and next to allow the number of the garrison to be reduced with safety when they had to go far for provisions. For some days there were no serious engagements, but slight skirmishes in the marshy plain which extended between the two camps. The capture, however, of a few foragers did not fail to swell the presumption of the barbarians, which was still more increased by the arrival of Commius, although he had brought only five hundred German cavalry.

The enemy remained for several days shut up in its impregnable position. Caesar judged that an assault would cost too many lives; an investment alone seemed to him opportune, but it would require a greater number of troops.

He wrote thereupon to Trebonius to send him as soon as possible the Thirteenth legion, which, under the command of T. Sextius, was in winter quarters among the Bituriges, to join it with the Sixth and the Fourteenth (which the first of these lieutenants commanded at Genabum),and to come himself with these three legions by forced marches.

During this time he employed the numerous cavalry of the Remi, the Lingones and the other allies, to protect the foragers and to prevent surprises, but this daily service, as is often the case, ended by being negligently performed. And one day the Remi, pursuing the Bellovaci with too much ardor, fell into an ambuscade. In withdrawing they were surrounded by foot-soldiers in the midst of whom Vertiscus, their chief, met with his death. True to his Gaulish nature, he would not allow his age to exempt him from commanding and mounting on horseback, although he was hardly able to keep his seat. His death and this feeble advantage raised the self-confidence of the barbarians still more, but it rendered the Romans more circumspect.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.