Cleopatra was an extraordinary person. At her death she was but thirty-eight years of age. Her power rested not so much on actual beauty as on her fascinating manners and her extreme readiness of wit.

Today’s installment concludes Death of Antony and Cleopatra,

our selection from A History of Rome by Henry George Liddell published in 1855. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of eleven thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously on Death of Antony and Cleopatra.

Time: August 30 BC

Place: Alexandria, Egypt

When Antony and Cleopatra arrived off Alexandria they put a bold face upon the matter. Some time passed before the real state of the case was known; but it soon became plain that Egypt was at the mercy of the conqueror. The Queen formed all kinds of wild designs. One was to transport the ships that she had saved across the Isthmus of Suez and seek refuge in some distant land where the name of Rome was yet unknown. Some ships were actually drawn across, but they were destroyed by the Arabs, and the plan was abandoned. She now flattered herself that her powers of fascination, proved so potent over Caesar and Antony, might subdue Octavian. Secret messages passed between the conqueror and the Queen; nor were Octavian’s answers such as to banish hope.

Antony, full of repentance and despair, shut himself up in Pharos, and there remained in gloomy isolation.

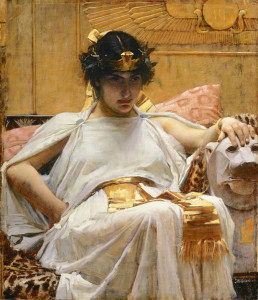

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

In July, B.C. 30, Octavian appeared before Pelusium. The place was surrendered without a blow. Yet, at the approach of the conqueror, Antony put himself at the head of a division of cavalry and gained some advantage. But on his return to Alexandria he found that Cleopatra had given up all her ships; and no more opposition was offered. On the 1st of August (Sextilis, as it was then called) Octavian entered the open gates of Alexandria. Both Antony and Cleopatra sought to win him. Antony’s messengers the conqueror refused to see; but he still used fair words to Cleopatra. The Queen had shut herself up in a sort of mausoleum built to receive her body after death, which was not approachable by any door; and it was given out that she was really dead. All the tenderness of old times revived in Antony’s heart. He stabbed himself, and in a dying state ordered himself to be laid by the side of Cleopatra. The Queen, touched by pity, ordered her expiring lover to be drawn up by cords into her retreat, and bathed his temples with her tears.

After he had breathed his last, she consented to see Octavian. Her penetration soon told her that she had nothing to hope from him. She saw that his fair words were only intended to prevent her from desperate acts and reserve her for the degradation of his triumph. This impression was confirmed when all instruments by which death could be inflicted were found to have been removed from her apartments. But she was not to be so baffled. She pretended all submission; but when the ministers of Octavian came to carry her away, they found her lying dead upon her couch, attended by her faithful waiting-women, Iras and Charmion. The manner of her death was never ascertained; popular belief ascribed it to the bite of an asp which had been conveyed to her in a basket of fruit.

Thus died Antony and Cleopatra. Antony was by nature a genial, open-hearted Roman, a good soldier, quick, resolute, and vigorous, but reckless and self-indulgent, devoid alike of prudence and of principle. The corruptions of the age, the seductions of power, and the evil influence of Cleopatra paralyzed a nature capable of better things. We know him chiefly through the exaggerated assaults of Cicero in his Philippic, and the narratives of writers devoted to Octavian. But after all deductions for partial representation, enough remains to show that Antony had all the faults of Caesar, with little of his redeeming greatness.

Cleopatra was an extraordinary person. At her death she was but thirty-eight years of age. Her power rested not so much on actual beauty as on her fascinating manners and her extreme readiness of wit. In her follies there was a certain magnificence which excites even a dull imagination. We may estimate the real power of her mental qualities by observing the impression her character made upon the Roman poets of the time. No meditated praises could have borne such testimony to her greatness as the lofty strain in which Horace celebrates her fall and congratulates the Roman world on its escape from the ruin which she was threatening to the Capitol.

Octavian dated the years of his imperial monarchy from the day of the battle of Actium. But it was not till two years after (the summer of B.C. 29) that he established himself in Rome as ruler of the Roman world. Then he celebrated three magnificent triumphs, after the example of his uncle the great dictator, for his victories in Dalmatia, at Actium, and in Egypt. At the same time the temple of Janus was closed–notwithstanding that border wars still continued in Gaul and Spain–for the first time since the year B.C. 235. All men drew breath more freely, and all except the soldiery looked forward to a time of tranquility. Liberty and independence were forgotten words. After the terrible disorders of the last century, the general cry was for quiet at any price. Octavian was a person admirably fitted to fulfill these aspirations. His uncle Julius was too fond of active exertion to play such a part well. Octavian never shone in war, while his vigilant and patient mind was well fitted for the discharge of business. He avoided shocking popular feeling by assuming any title savoring of royalty; but he enjoyed by universal consent an authority more than regal.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Death of Antony and Cleopatra by Henry George Liddell from his book A History of Rome published in 1855. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Marc Antony from History.com, on Cleopatra from The Smithsonian and National Geographic Magazines.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.