Next day their camp was surrounded by the nearest chief and his warriors, evidently bent on plunder.

Continuing Livingstone’s African Discoveries,

our selection from David Livingstone by Thomas Hughes published in 1889. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in 3.5 easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Livingstone’s African Discoveries.

Time: 1854

Place: Central Africa

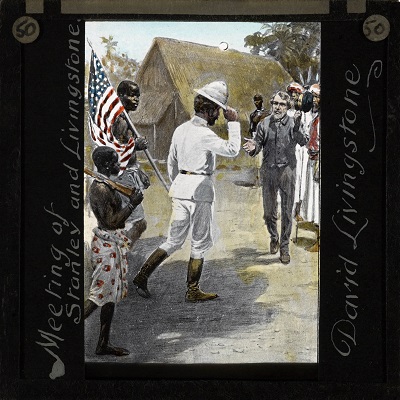

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Happily Livingstone had brought back with him several Balonda children who had been carried off by the Makololo. This, and his speeches to Manenko, the chieftainess of the district and niece of Shinte, the head chief of the Balonda, gained them a welcome. This Amazon was a strapping young woman of twenty, who led their party through the forest at a pace which tried the best walkers. She seems to have been the only native whose will ever prevailed against Livingstone’s.

He intended to proceed up to her uncle Shinte’s town in canoes: she insisted that they should march by land, and ordered her people to shoulder his baggage in spite of him. “My men succumbed, and left me powerless. I was moving off in high dudgeon to the canoes, when she kindly placed her hand on my shoulder, and with a motherly look said, ‘Now, my little man, just do as the rest have done.’ My feeling of annoyance of course vanished, and I went out to try for some meat. My men, in admiration of her pedestrian powers, kept remarking, ‘Manenko is a soldier,’ and we were all glad when she proposed a halt for the night.”

Shinte received them in his town, the largest and best laid out that Livingstone had seen in Central Africa, on a sort of throne covered with leopard-skin. The kotla, or place of audience, was one hundred yards square. Though in the sweating stage of an intermittent fever, Livingstone held his own with the chief, gave him an ox as “his mouth was bitter from want of flesh,” advised him to open a trade in cattle with the Makololo, and to put down the slave-trade; and, after spending more than a week with him, left amid the warmest professions of friendship. Shinte found him a guide of his tribe, Intemese by name, who was to stay by them till they reached the sea, and at a last interview hung round his neck a conical shell of such value that two of them, so his men assured him, would purchase a slave.

Soon they were out of Shinte’s territory, and Intemese became the plague of the party, though unluckily they could not dispense with him altogether in crossing the great flooded plains of Lebala. They camped at night on mounds, where they had to trench round each hut and use the earth to raise their sleeping places. “My men turned out to work most willingly, and I could not but contrast their conduct with that of Intemese, who was thoroughly imbued with the slave spirit, and lied on all occasions to save himself trouble.” He lost the pontoon, too, thereby adding greatly to their troubles.

They now came to the territory of another great chief, Katema, who received them hospitably, sending food and giving them solemn audience in his kotla surrounded by his tribe. A tall man of forty, dressed in a snuff-brown coat with a broad band of tinsel down the arms, and a helmet of beads and feathers. He carried a large fan with charms attached, which he waved constantly during the audience, often laughing heartily — “a good sign, for a man who shakes his sides with mirth is seldom difficult to deal with.”

“I am the great Moene Katema!” was his address; “I and my fathers have always lived here, and there is my father’s house. I never killed any of the traders; they all come to me. I am the great Moene Katema, of whom you have heard.” On hearing Livingstone’s object, he gave him three guides, who would take him by a northern route, along which no traders had passed, to avoid the plains, impassable from the floods. He accepted Livingstone’s present of a shawl, a razor, some beads and buttons, and a powder-horn graciously, laughing at his apologies for its smallness, and asking him to bring a coat from Loanda, as the one he was wearing was old.

From this point troubles multiplied, and they began to be seriously pressed for food. The big game had disappeared, and they were glad to catch moles and mice. Every chief demanded a present for allowing them to pass, and the people of the villages charged exorbitantly for all supplies. On they floundered, however, through flooded forests. In crossing the river Loka, Livingstone’s ox got away from him, and he had to strike out for the farther bank. “My poor fellows were dreadfully alarmed, and about twenty of them made a simultaneous rush into the water for my rescue, and just as I reached the opposite bank one seized me by the arms and another clasped me round the body. When I stood up it was most gratifying to see them all struggling toward me. Part of my goods were brought up from the bottom when I was safe. Great was their pleasure when they found I could swim like themselves, and I felt most grateful to those poor heathens for the promptitude with which they dashed in to my rescue.” Farther on, the people tried to frighten them with the account of the deep rivers they had yet to cross, but his men laughed. “‘We can all swim,’ they said; ‘who carried the white man across the river but himself?’ I felt proud of their praise.”

On March 4th they reached the country of the Chiboques, a tribe in constant contact with the slave-dealers. Next day their camp was surrounded by the nearest chief and his warriors, evidently bent on plunder. They paused when they saw Livingstone seated on his camp-stool, with his double-barrelled gun across his knees, and his Makololos ready with their javelins.

The chief and his principal men sat down in front at Livingstone’s invitation to talk over the matter, and a palaver began as to the fine claimed by the Chiboque. “The more I yielded, the more unreasonable they became, and at every fresh demand a shout was raised, and a rush made round us with brandished weapons. One young man even made a charge at my head from behind, but I quickly brought round the muzzle of my gun to his mouth and he retreated. My men behaved with admirable coolness. The chief and his counsellors, by accepting my invitation to be seated, had placed themselves in a trap, for my men had quietly surrounded them and made them feel that there was no chance of escaping their spears. I then said that as everything had failed to satisfy them they evidently meant to fight; and if so, they must begin, and bear the blame before God. I then sat silent for some time. It was certainly rather trying, but I was careful not to seem flurried, and, having four barrels ready for instant action, looked quietly at the savage scene around.” The palaver began again, and ended in the exchange of an ox for a promise of food, in which he was wofully cheated. “It was impossible to help laughing, but I was truly thankful that we had so far gained our point as to be allowed to pass without shedding blood.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

David Livingstone begins here. Thomas Hughes begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.