Fulvia, wife of Antony, was a woman of fierce passions and ambitious spirit. She had not been invited to follow her husband to the East.

Continuing Death of Antony and Cleopatra,

our selection from A History of Rome by Henry George Liddell published in 1855. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments.

Previously on Death of Antony and Cleopatra.

Time: August 30 BC

Place: Alexandria, Egypt

The battle of Philippi was in reality the closing scene of the republican drama. But the rivalship of the triumvirs prolonged for several years the divided state of the Roman world; and it was not till after the crowning victory of Actium that the imperial government was established in its unity. We shall, therefore, here add a rapid narrative of the events which led to that consummation.

The hopeless state of the republican or rather the senatorial party was such that almost all hastened to make submission to the conquerors: those whose sturdy spirit still disdained submission resorted to Sext Pompeius in Sicily. Octavian, still suffering from ill-health, was anxious to return to Italy; but before he parted from Antony, they agreed to a second distribution of the provinces of the empire. Antony was to have the Eastern world; Octavian the Western provinces. To Lepidus, who was not consulted in this second division, Africa alone was left. Sext Pompeius remained in possession of Sicily.

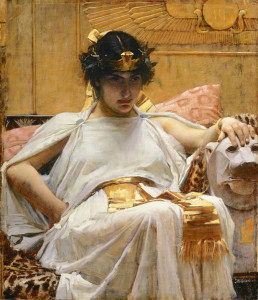

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Antony at once proceeded to make a tour through Western Asia, in order to exact money from its unfortunate people. About midsummer (B.C. 41) he arrived at Tarsus, and here he received a visit which determined the future course of his life and influenced Roman history for the next ten years.

Antony had visited Alexandria fourteen years before, and had been smitten by the charms of Cleopatra, then a girl of fifteen. She became Caesar’s paramour, and from the time of the dictator’s death Antony had never seen her. She now came to meet him in Cilicia. The galley which carried her up the Cydnus was of more than oriental gorgeousness: the sails of purple; oars of silver, moving to the sound of music; the raised poop burnished with gold. There she lay upon a splendid couch, shaded by a spangled canopy; her attire was that of Venus; around her flitted attendant cupids and graces. At the news of her approach to Tarsus, the triumvir found his tribunal deserted by the people. She invited him to her ship, and he complied. From that moment he was her slave. He accompanied her to Alexandria, exchanged the Roman garb for the Graeco-Egyptian costume of the court, and lent his power to the Queen to execute all her caprices.

Meanwhile Octavian was not without his difficulties. He was so ill at Brundusium that his death was reported at Rome. The veterans, eager for their promised rewards, were on the eve of mutiny. In a short time Octavian was sufficiently recovered to show himself. But he could find no other means of satisfying the greedy soldiery than by a confiscation of lands more sweeping than that which followed the proscription of Sylla. The towns of Cisalpine Gaul were accused of favoring Dec. Brutus, and saw nearly all their lands handed over to new possessors. The young poet, Vergil, lost his little patrimony, but was reinstated at the instance of Pollio and Maecenas, and showed his gratitude in his First Eclogue. Other parts of Italy also suffered: Apulia, for example, as we learn from Horace’s friend Ofellus, who became the tenant of the estate which had formerly been his own.

But these violent measures deferred rather than obviated the difficulty. The expulsion of so many persons threw thousands loose upon society, ripe for any crime. Many of the veterans were ready to join any new leader who promised them booty. Such a leader was at hand.

Fulvia, wife of Antony, was a woman of fierce passions and ambitious spirit. She had not been invited to follow her husband to the East. She saw that in his absence imperial power would fall into the hands of Octavian. Lucius, brother of Mark Antony, was consul for the year, and at her instigation he raised his standard at Praeneste. But L. Antonius knew not how to use his strength; and young Agrippa, to whom Octavian intrusted the command, obliged Antonius and Fulvia to retire northward and shut themselves up in Perusia. Their store of provisions was so small that it sufficed only for the soldiery. Early in the next year Perusia surrendered, on condition that the lives of the leaders should be spared. The town was sacked; the conduct of L. Antonius alienated all Italy from his brother.

While his wife, his brother, and his friends were quitting Italy in confusion, the arms of Antony suffered a still heavier blow in the Eastern provinces, which were under his special government. After the battle of Philippi, Q. Labienus, son of Caesar’s old lieutenant Titus, sought refuge at the court of Orodes, king of Parthia. Encouraged by the proffered aid of a Roman officer, Pacorus (the King’s son) led a formidable army into Syria. Antony’s lieutenant was entirely routed; and while Pacorus with one army poured into Palestine and Phoenicia, Q. Labienus with another broke into Cilicia. Here he found no opposition; and, overrunning all Asia Minor even to the Ionian Sea, he assumed the name of Parthicus, as if he had been a Roman conqueror of the people whom he served.

These complicated disasters roused Antony from his lethargy. He sailed to Tyre, intending to take the field against the Parthians; but the season was too far advanced, and he therefore crossed the Aegean to Athens, where he found Fulvia and his brother, accompanied by Pollio, Plancus, and others, all discontented with Octavian’s government. Octavian was absent in Gaul, and their representation of the state of Italy encouraged him to make another attempt. Late in the year (41) Antony formed a league with Sext Pompeius; and while that chief blockaded Thurii and Consentia, Antony assailed Brundusium. Agrippa was preparing to meet this new combination; and a fresh civil war was imminent. But the soldiery was weary of war: both armies compelled their leaders to make pacific overtures, and the new year was ushered in by a general peace, which was rendered easier by the death of Fulvia.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information on Marc Antony from History.com, on Cleopatra from The Smithsonian and National Geographic Magazines.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.