After the first battle of Philippi it would have still been politic in Brutus to abstain from battle. The triumviral armies were in great distress, and every day increased their losses.

Continuing Death of Antony and Cleopatra,

our selection from A History of Rome by Henry George Liddell published in 1855. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments.

Previously on Death of Antony and Cleopatra.

Time: August 30 BC

Place: Alexandria, Egypt

Meantime Antony’s lieutenants had crossed the Ionian Sea and penetrated without opposition into Thrace. The republican leaders found them at Philippi. The army of Brutus and Cassius amounted to at least eighty thousand infantry, supported by twenty thousand horse; but they were ill-supplied with experienced officers. For M. Valerius Messalla, a young man of twenty-eight, held the chief command after Brutus and Cassius; and Horace, who was but three-and-twenty, the son of a freedman, and a youth of feeble constitution, was appointed a legionary tribune. The forces opposed to them would have been at once overpowered had not Antony himself opportunely arrived with the second corps of the triumviral army. Octavian was detained by illness at Dyrrhachium, but he ordered himself to be carried on a litter to join his legions. The army of the triumvirs was now superior to the enemy; but their cavalry, counting only thirteen thousand, was considerably weaker than the force opposed to it. The republicans were strongly posted upon two hills, with intrenchments between: the camp of Cassius upon the left next the sea, that of Brutus inland on the right. The triumviral army lay upon the open plain before them, in a position rendered unhealthy by marshes; Antony, on the right, was opposed to Cassius; Octavian, on the left, fronted Brutus. But they were ill-supplied with provisions and anxious for a decisive battle. The republicans, however, kept to their intrenchments, and the other party began to suffer severely from famine.

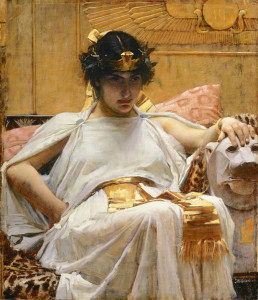

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Determined to bring on an action, Antony began works for the purpose of cutting off Cassius from the sea. Cassius had always opposed a general action, but Brutus insisted on putting an end to the suspense, and his colleague yielded. The day of the attack was probably in October. Brutus attacked Octavian’s army, while Cassius assaulted the working parties of Antony. Cassius’ assault was beaten back with loss, but he succeeded in regaining his camp in safety. Meanwhile, Messalla, who commanded the right wing of Brutus’ army, had defeated the host of Octavian, who was still too ill to appear on the field, and the republican soldiers penetrated into the triumvirs’ camp. Presently his litter was brought in stained with blood, and the corpse of a young man found near it was supposed to be Octavian’s. But Brutus, not receiving any tidings of the movements of Cassius, became so anxious for his fate that he sent off a party of horse to make inquiries, and neglected to support the successful assaults of Messalla.

Cassius, on his part, discouraged at his ill-success, was unable to ascertain the progress of Brutus. When he saw the party of horse he hastily concluded that they belonged to the enemy, and retired into his tent with his freedman Pindarus. What passed there we know not for certain. Cassius was found dead, with the head severed from the body. Pindarus was never seen again. It was generally believed that Pindarus slew his master in obedience to orders; but many thought that he had dealt a felon blow. The intelligence of Cassius’ death was a heavy blow to Brutus. He forgot his own success, and pronounced the elegy of Cassius in the well-known words, “There lies the last of the Romans.” The praise was ill-deserved. Except in his conduct of the war against the Parthians, Cassius had never played a worthy part.

After the first battle of Philippi it would have still been politic in Brutus to abstain from battle. The triumviral armies were in great distress, and every day increased their losses. Reinforcements coming to their aid by sea were intercepted–a proof of the neglect of the republican leaders in not sooner bringing their fleet into action. Nor did Brutus ever hear of this success. He was ill-fitted for the life of the camp, and after the death of Cassius he only kept his men together by largesse and promises of plunder. Twenty days after the first battle he led them out again. Both armies faced one another. There was little manoeuvring. The second battle was decided by numbers and force, not by skill; and it was decided in favor of the triumvirs. Brutus retired with four legions to a strong position in the rear, while the rest of his broken army sought refuge in the camp. Octavian remained to watch them, while Antony pursued the republican chief. Next day Brutus endeavored to rouse his men to another effort; but they sullenly refused to fight; and Brutus withdrew with a few friends into a neighboring wood. Here he took them aside one by one, and prayed each to do him the last service that a Roman could render to his friend. All refused with horror; till at nightfall a trusty Greek freedman named Strato held the sword, and his master threw himself upon it. Most of his friends followed the sad example. The body of Brutus was sent by Antony to his mother. His wife Portia, the daughter of Cato, refused all comfort; and being too closely watched to be able to slay herself by ordinary means, she suffocated herself by thrusting burning charcoal into her mouth. Massalla, with a number of other fugitives, sought safety in the island of Thasos, and soon after made submission to Antony.

The name of Brutus has, by Plutarch’s beautiful narrative, sublimed by Shakespeare, become a byword for self-devoted patriotism. This exalted opinion is now generally confessed to be unjust. Brutus was not a patriot, unless devotion to the party of the senate be patriotism. Toward the provincials he was a true Roman, harsh and oppressive. He was free from the sensuality and profligacy of his age, but for public life he was unfit. His habits were those of a student. His application was great, his memory remarkable. But he possessed little power of turning his acquirements to account; and to the last he was rather a learned man than a man improved by learning. In comparison with Cassius, he was humane and generous; but in all respects his character is contrasted for the worse with that of the great man from whom he accepted favors and then became his murderer.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information on Marc Antony from History.com, on Cleopatra from The Smithsonian and National Geographic Magazines.

Like!! Really appreciate you sharing this blog post.Really thank you! Keep writing.