Brutus and Cassius left Italy in the autumn of B.C. 44 and repaired to the provinces which had been allotted to them, though by Antony’s influence the senate had transferred Macedonia from Brutus to his own brother Caius, and Syria from Cassius to Dolabella.

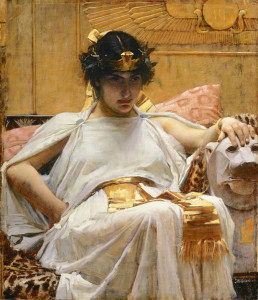

Continuing Death of Antony and Cleopatra,

our selection from A History of Rome by Henry George Liddell published in 1855. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eleven easy 5 minute installments.

Previously on Death of Antony and Cleopatra.

Time: August 30 BC

Place: Alexandria, Egypt

As soon as their secret business was ended, the triumvirs determined to enter Rome publicly. Hitherto they had not published more than seventeen names of the proscribed. They made their entrance severally on three successive days, each attended by a legion. A law was immediately brought in to invest them formally with the supreme authority, which they had assumed. This was followed by the promulgation of successive lists, each larger than its predecessor.

Among the victims, far the most conspicuous was Cicero. With his brother Quintus, the old orator had retired to his Tusculan villa after the battle of Mutina; and now they endeavored to escape in the hope of joining Brutus in Macedonia; for the orator’s only son was serving as a tribune in the liberator’s army. After many changes of domicile they reached Astura, a little island near Antium, where they found themselves short of money, and Quintus ventured to Rome to procure the necessary supply. Here he was recognized and seized, together with his son. Each desired to die first, and the mournful claim to precedence was settled by the soldiers killing both at the same moment.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Meantime Cicero had put to sea. But even in this extremity he could not make up his mind to leave Italy, and put to land at Circeii. After further hesitation he again embarked, and again sought the Italian shore near Formiae. For the night he stayed at his villa near that place, and next morning would not move, exclaiming: “Let me die in my own country–that country which I have so often saved.” But his faithful slaves forced him into a litter and carried him again toward the coast. Scarcely were they gone when a band of Antony’s bloodhounds reached his villa, and were put upon the track of their victim by a young man who owed everything to the Ciceros. The old orator from his litter saw the pursuers coming up. His own followers were strong enough to have made resistance, but he desired them to set the litter down. Then, raising himself on his elbow, he calmly waited for the ruffians and offered his neck to the sword. He was soon despatched. The chief of the band, by Antony’s express orders, hewed off the head and hands and carried them to Rome. Fulvia, the widow of Clodius and now the wife of Antony, drove her hairpin through the tongue which had denounced the iniquities of both her husbands. The head which had given birth to the Second Philippic, and the hands which had written it, were nailed to the Rostra, the home of their eloquence. The sight and the associations raised feelings of horror and pity in every heart. Cicero died in his sixty-fourth year.

Brutus and Cassius left Italy in the autumn of B.C. 44 and repaired to the provinces which had been allotted to them, though by Antony’s influence the senate had transferred Macedonia from Brutus to his own brother Caius, and Syria from Cassius to Dolabella. C. Antonius was already in possession of parts of Macedonia; but Brutus succeeded in dislodging him. Meanwhile Cassius, already well known in Syria for his successful conduct of the Parthian War, had established himself in that province before he heard of the approach of Dolabella. This worthless man left Italy about the same time as Brutus and Cassius, and at the head of several legions marched without opposition through Macedonia into Asia Minor. Here C. Trebonius had already arrived. But he was unable to cope with Dolabella; and the latter surprised him and took him prisoner at Smyrna. He was put to death with unseemly contumely in Dolabella’s presence. This was in February, 43; and thus two of Caesar’s murderers, in less than a year’s time, felt the blow of retributive justice. When the news of this piece of butchery reached Rome, Cicero, believing that Octavian was a puppet in his hands, was ruling Rome by the eloquence of his Philippics. On his motion Dolabella was declared a public enemy. * Cassius lost no time in marching his legions into Asia, to execute the behest of the senate, though he had been dispossessed of his province by the senate itself. Dolabella threw himself into Laodicea, where he sought a voluntary death.

[* He had divorced Tullia, the orator’s daughter, before he left Italy.]

By the end of B.C. 43, therefore, the whole of the East was in the hands of Brutus and Cassius. But instead of making preparations for war with Antony, the two commanders spent the early part of the year 42 in plundering the miserable cities of Asia Minor. Brutus demanded men and money of the Lycians; and, when they refused, he laid siege to Xanthus, their principal city. The Xanthians made the same brave resistance which they had offered five hundred years before to the Persian invaders. They burned their city and put themselves to death rather than submit. Brutus wept over their fate and abstained from further exactions. But Cassius showed less moderation; from the Rhodians alone, though they were allies of Rome, he demanded all their precious metals. After this campaign of plunder, the two chiefs met at Sardis and renewed the altercations which Cicero had deplored in Italy. It is probable that war might have broken out between them had not the preparations of the triumvirs waked them from their dream of security. It was as he was passing over into Europe that Brutus, who continued his studious habits amid all disquietudes, and limited his time of sleep to a period too small for the requirements of health, was dispirited by the vision which Shakespeare, after Plutarch, has made famous. It was no doubt the result of a diseased frame, though it was universally held to be a divine visitation. As he sat in his tent in the dead of night, he thought a huge and shadowy form stood by him; and when he calmly asked, “What and whence art thou?” it answered, or seemed to answer: “I am thine evil genius, Brutus: we shall meet again at Philippi.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information on Marc Antony from History.com, on Cleopatra from The Smithsonian and National Geographic Magazines.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.