In Tasmania, the main difficulty arose from the drain of emigrants.

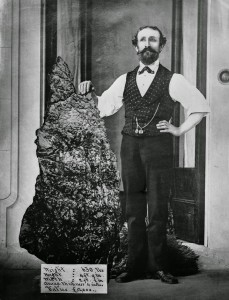

Featuring Edward Jenks

Previously on Gold Discovered in Australia. Now we continue.

Time: February 12, 1851

Place: Lewes Pond Creek

gold fields dug up in 1872.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

After the comparative failure of the gold-diggings in South Australia, the Government had wisely set itself to secure some part of the prosperity of the gold discoveries for its colony by establishing both land and river traffic routes. In these efforts it was highly successful. Many South Australians made handsome fortunes by sending provisions to the Buninyong and Mount Alexander districts, and the new steamers on the Murray proved a source of profit to the colony which lasted until the development of the railroad system. Unfortunately, this prosperity could hardly be realized at the time, owing to the great scarcity of coined money in the colony. In 1851 the privilege of coining was still jealously monopolized by the mint in London; while the rapid expansion of business in the latter part of that year had rendered the supply of coin in Australia totally inadequate to the demand.

Very soon after the discoveries, Governor Fitzroy had sent home a memorial from the Legislative Council at Sydney, praying for the establishment of a branch mint in that city, and similar applications soon followed from the other colonies. On March 22, 1853, a Treasury minute sanctioned the applications, and colonial mints were shortly afterward established by order in council. But in the mean while the South Australians had got over their difficulty by passing a colonial act authorizing the issue by the Colonial Government of gold ingots, of slightly higher intrinsic value than the coins they were supposed to represent, stamped with an authentic mark. These ingots were not made legal tender, and the only object of the government mark was to guarantee quality and weight. But they were generally accepted in official and commercial transactions, they tided over the crisis of scarcity, and the Home Government, though with due official caution, approved the action of Governor Young.

In Tasmania, the main difficulty arose from the drain of emigrants. In August, 1851, Sir William Denison wrote home urging the transportation of more convicts or “probationers,” on the ground that there would be a great demand for foodstuffs by the neighboring colonies, while the supply of agricultural laborers would be shorter than ever. Both Tasmania and South Australia united in deciding upon the continuance of the system by which free emigrants were sent out at the expense of the land fund of each colony, notwithstanding that such emigrants would probably leave for Victoria immediately after their arrival. Of the existence of this contingency there could be little doubt. On January 16, 1852, the Governor of Tasmania wrote: “I have a number of men who have come back from Mount Alexander after an absence from this colony of not more than eight weeks, with gold to the value of one hundred twenty pounds to one thousand pounds.” During the five months which followed the writing of this letter, four thousand persons (most of them wage-earners in the prime of life) left Tasmania for Victoria. As the whole population of Tasmania was at this time only about fifty thousand, the matter was serious. Nevertheless, Tasmania tided safely over the difficulties of the gold period, and even was able to help her sorely tried sister.

For it was upon the newly established Government at Melbourne that the strain of the new era most severely fell. The Government at Sydney was an old and tried institution, with traditions of more than half a century, and a staff of experienced officials under an exceptionally able chief. When Hargraves made his discoveries in 1851, the population of the mother-colony was nearly a quarter of a million, exclusive of the Port Phillip district, and such a population meant a government organization of corresponding magnitude. Moreover, the people of New South Wales had always, from circumstances, been accustomed to much governmental control, and did not resent it; while Victoria had been started as a colony whose people were too prosperous and contented to require more than a minimum of guidance. When the gold discoveries suddenly drew into the colony, not merely the most turbulent characters of Australia, but the crews of deserted ships and the general offscourings of the civilized world, and when, overcome by the contagion, the government officials threw up their posts, one and all, and started for the diggings, it became evident that the Lieutenant-Governor had his hands full. Even so early as November, 1851, he began to anticipate trouble from the preemptive clauses of the Crown Lands Leasing Act of 1847, by which the squatters had a right to purchase land in the neighborhood of the gold-fields. The claims of the squatters barred the way, and the squatters themselves looked with small favor upon a class of men whom they regarded as troublesome intruders, and whose proceedings rendered it almost impossible for the pastoralists to procure sufficient labor to carry on their operations. The squatters chose to overlook two important facts; viz., that they had themselves originally acquired their position precisely as the digger acquired his, and that the presence of the digger, if it raised the price of labor, also enormously increased the prices of the squatter’s produce.

But more immediate financial troubles began to press upon the Government. It had been necessary, not merely to add largely to the number of the official staff–to provide additional police, commissioners, magistrates, customs officers, etc.–but also to increase their pay in some proportion to the greatly increased cost of living. Even with an increase in their salaries of 50 or 100 per cent, the subordinate officials would not stay. The sight of the reckless and prosperous diggers who came down to Melbourne to spend the Christmas of 1851, and who flung their gold about recklessly, was too much for the feelings of the civilians. They deserted in troops.

On January 12, 1852, Lieutenant-Governor Latrobe wrote: “The police in town and country have almost entirely abandoned duty,” and he begged of the Secretary of State to send military aid. In May, 1852, Sir John Pakington replied, promising six companies of the Fifty-ninth Regiment from China, but subsequently decided to send a whole regiment direct from England. A man-of-war was also to be stationed in Australian waters. A still more welcome assistance came in the early part of the year from the Governor of Tasmania, who sent, at Latrobe’s earnest request, a body of two hundred pensioners, who had been serving as convict guards, and who might be expected to resist those temptations which, if yielded to, would result in the loss of their pensions. But all this assistance meant money, and the Government soon fell into sore straits.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.