But the ugliest feature of the whole affair was yet to be revealed. Out of the large number of prisoners taken at the capture of the stockade, only thirteen were committed for trial, the magistrates being instructed to commit only when the evidence was of the clearest nature.

Featuring Edward Jenks

Previously on Gold Discovered in Australia. Now we continue.

Time: February 12, 1851

Place: Lewes Pond Creek

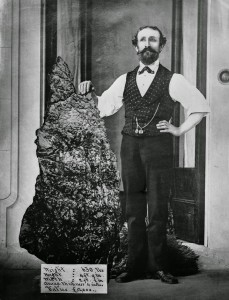

gold fields dug up in 1872.

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The Governor at once ordered all the available military force to Ballarat; but, before reinforcements arrived, the coolness and promptitude of Captain Thomas — the officer in command of the troops on the Ballarat goldfield when the riot of November 30th took place—had nipped the insurrection in the bud. Captain Thomas saw that, while the Eureka Stockade threatened to become a serious obstacle to the Government if its completion were allowed, in its uncompleted state it was really a source of weakness to the insurgents. By collecting their forces in one spot, and thus rendering them more exposed to a crushing attack, and by drawing off the men who threatened the government camp, it really left the commander of the troops free to act with decision. Accordingly, Captain Thomas at once determined to attack the position. Assembling his forces (somewhat fewer than two hundred men) at three o’clock on the morning of December 3rd, he moved toward the stockade.

At about one hundred fifty yards from the entrenchments, he was perceived by the scouts of the insurgents, who promptly fired on the advancing troops. Thomas himself, Pasley (his aide-de-camp), Rede (the resident commissioner), and Racket (the stipendiary magistrate), all of whom were present at the attack, positively assert that the insurgents fired before a shot was discharged by the troops. Upon this reception Captain Thomas gave the order to fire, and the entrenchments were carried with a rush after about ten minutes of sharp fighting. Captain Wise was fatally wounded, and three privates were killed outright; one officer and eleven privates were wounded. Of the insurgents, about thirty were known to have been killed, and many more wounded. Nearly one hundred twenty prisoners were taken. The effect of the victory was, so far as local disturbances were concerned, instantaneous. Even before the reinforcements under General Nickle appeared, all resistance to the authorities had died away; and, though the Governor at once proclaimed a state of martial law, he was able to recall the proclamation in less than a week.

In other districts of the colony the effect was, for a while, doubtful. The extreme reluctance of Englishmen to admit the necessity for military interference by the Government told strongly in favor of the rioters. There was some danger that Melbourne and Geelong, left almost entirely unprotected by the concentration of troops and police at Ballarat, would be taken possession of by rioters from the country districts, and Sir Charles Hotham made hasty application to Sir William Denison, the Governor of Tasmania, for military assistance. Very soon, however, the feelings of orderly citizens asserted themselves. Special constables were sworn in at Melbourne and Geelong, marines from two men-of-war stationed at Port Phillip guarded the prisons and the powder stores, wealthy men volunteered to serve as mounted police, and the arrival of the Ninety-ninth Regiment from Tasmania on December 10th dealt a final blow to the hopes of the insurgents. Even before this event, all the respectable classes in the community had rallied round the Governor, and he felt himself in a position to defy further outbreaks.

But the ugliest feature of the whole affair was yet to be revealed. Out of the large number of prisoners taken at the capture of the stockade, only thirteen were committed for trial, the magistrates being instructed to commit only when the evidence was of the clearest nature. It being considered impossible to obtain an impartial trial by a local jury, the prisoners were brought down to Melbourne, and, after various delays, the charges were proceeded with on February 20, 1855. A Boston negro, named John Joseph, and a reporter for the Ballarat Times, named Manning, were first tried. The latter may have been merely led away by professional ardor in the pursuit of “copy,” though the fact that he had been openly drilled and instructed in the use of a pike by the insurgents would seem to show that his zeal was somewhat excessive.

In the case of Joseph, the evidence was overwhelming; he had actually been seen to fire upon the troops, and he was captured in a tent which had been used as a guardroom by the insurgents. No counter-evidence was offered, the prisoners’ counsel relying entirely on the alleged absence of treasonable intention. Nevertheless, both prisoners were speedily acquitted, and, although the Government wisely withdrew the remaining cases for the time, subsequent trials produced similar results. Ultimately, however, the difficulties of the situation were allayed by the reforms introduced on the recommendation of the commission appointed to consider the whole subject of the goldfields. This body presented,

on March 27, 1855, an extremely able report, in which it recommended the abolition of the license fee and the substitution therefor of a “miners’ right” or Crown permission, lasting for a year, and granted for a nominal fee of one pound, to occupy for mining purposes a specific piece of Crown land. The deficiency in revenue anticipated from the abolition of license fees was to be met by the imposition of an export duty upon gold at the rate of a half-crown an ounce.

The commission strongly recommended the granting of the political franchise to holders of “miners’ rights,” and the provision of liberal facilities for the acquisition of land by the miners. It also advocated the simplification of the existing complex system of government in the mining districts, whereby commissioners, police authorities, commissariat officials, and magistrates all worked independently of each other, and suggested the substitution therefor of experienced “wardens” at the head of elective boards, who should not only dispose, with the aid of skilled assessors, of disputes specially connected with mining operations, but who should have power to issue by-laws adapted to the special requirements of each district.

These recommendations were for the most part carried out by legislation of the same year (1855), and, before his lamented death in December, 1855, Sir Charles Hotham had the happiness being able to report to the Home Government the almost perfect tranquility of the goldfields. Moreover, the revenue had not suffered by the substitution of the export duty for the license fees; but the collector of customs was of opinion that the result of the change had been to throw the entire burden of the tax upon the importers of the colony instead of upon the mining population. The Government was not, however, disposed to concern itself with considerations of abstract justice so long as it could collect a sufficient revenue without serious opposition.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Gold Discovered in Australia by Edward Jenks from his book A History of the Australasian Colonies published in 1895. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information here and here and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.