This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Solomon’s Reign.

Introduction

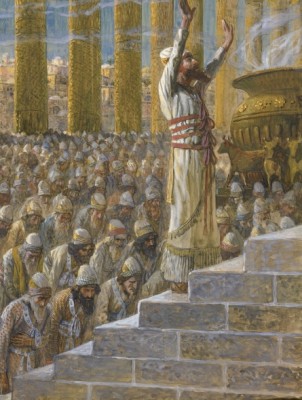

After all the tumultuous years from Moses and the exodus from Egypt, the wanderings in the desert, the conquest of Canaan, the struggles of the Judges, Saul and his time of troubles, David and his, Israel was at peace at last. The domain of the Hebrews was greater than at any other time, before or afterward. Now they began their next great task: the erection of a great shrine to enclose the sacred Ark of the Covenant. Honored in both history and fiction no human work of ancient or modern times has so impressed mankind as the building of Solomon’s Temple.

This selection is from History of the Jews by Henry Hart Milman published in 1829.

Henry Hart Milman was a historian working in religious history. His History of the Jews modernized scholarship of this sensitive area of history.

Time: 953 BC

Place: Jerusalem

Pubic domain image from Wikipedia.

Solomon succeeded to the Hebrew kingdom at the age of twenty. He was environed by designing, bold, and dangerous enemies. The pretensions of Adonijah still commanded a powerful party: Abiathar swayed the priesthood; Joab the army. The singular connection in public opinion between the title to the crown and the possession of the deceased monarch’s harem is well understood.[1] Adonijah, in making request for Abishag, a youthful concubine taken by David in his old age, was considered as insidiously renewing his claims to the sovereignty. Solomon saw at once the wisdom of his father’s dying admonition: he seized the opportunity of crushing all future opposition and all danger of a civil war. He caused Adonijah to be put to death; suspended Abiathar from his office, and banished him from Jerusalem: and though Joab fled to the altar, he commanded him to be slain for the two murders of which he had been guilty, those of Abner and Amasa. Shimei, another dangerous man, was commanded to reside in Jerusalem, on pain of death if he should quit the city. Three years afterward he was detected in a suspicious journey to Gath, on the Philistine border; and having violated the compact, he suffered the penalty.

Thus secured by the policy of his father from internal enemies, by the terror of his victories from foreign invasion, Solomon commenced his peaceful reign, during which Judah and Israel dwelt safely, “Every man under his vine and under his fig-tree, from Dan to Beersheba.” This peace was broken only by a revolt of the Edomites. Hadad, of the royal race, after the exterminating war waged by David and by Joab, had fled to Egypt, where he married the sister of the king’s wife. No sooner had he heard of the death of David and of Joab than he returned, and seems to have kept up a kind of predatory warfare during the reign of Solomon. Another adventurer, Rezon, a subject of Hadadezer, king of Zobah, seized on Damascus, and maintained a great part of Syria in hostility to Solomon.

Solomon’s conquest of Hamath Zobah in a later part of his reign, after which he built Tadmor in the wilderness and raised a line of fortresses along his frontier to the Euphrates, is probably connected with these hostilities.[2] The justice of Solomon was proverbial. Among his first acts after his accession, it is related that when he had offered a costly sacrifice at Gibeon, the place where the Tabernacle remained, God had appeared to him in a dream, and offered him whatever gift he chose: the wise king requested an understanding heart to judge the people. God not merely assented to his prayer, but added the gift of honor and riches. His judicial wisdom was displayed in the memorable history of the two women who contested the right to a child. Solomon, in the wild spirit of Oriental justice, commanded the infant to be divided before their faces: the heart of the real mother was struck with terror and abhorrence, while the false one consented to the horrible partition, and by this appeal to nature the cause was instantaneously decided.

The internal government of his extensive dominions next demanded the attention of Solomon. Besides the local and municipal governors, he divided the kingdom into twelve districts: over each of these he appointed a purveyor for the collection of the royal tribute, which was received in kind; and thus the growing capital and the immense establishments of Solomon were abundantly furnished with provisions. Each purveyor supplied the court for a month. The daily consumption of his household was three hundred bushels of finer flour, six hundred of a coarser sort; ten fatted, twenty other oxen; one hundred sheep; besides poultry, and various kinds of venison. Provender was furnished for forty thousand horses, and a great number of dromedaries. Yet the population of the country did not, at first at least, feel these burdens: “Judah and Israel were many, as the sand which is by the sea in multitude, eating and drinking, and making merry.”

The foreign treaties of Solomon were as wisely directed to secure the profound peace of his dominions. He entered into a matrimonial alliance with the royal family of Egypt, whose daughter he received with great magnificence; and he renewed the important alliance with the king of Tyre.[3] The friendship of this monarch was of the highest value in contributing to the great royal and national work, the building of the Temple. The cedar timber could only be obtained from the forests of Lebanon: the Sidonian artisans, celebrated in the Homeric poems, were the most skilful workmen in every kind of manufacture, particularly in the precious metals.

Footnotes:

Footnote 1: I Kings, i.

Footnote 2: I Kings, xi., 23; I Chron., viii., 3.

Footnote 3: After inserting the correspondence between King Solomon and King Hiram of Tyre, according to I Kings, v., Josephus asserts that copies of these letters were not only preserved by his countrymen, but also in the archives of Tyre. I presume that Josephus adverts to the statement of Tyrian historians, not to an actual inspection of the archives, which he seems to assert as existing and accessible.

| Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.