Our inquiry into the sources of the vast wealth which Solomon undoubtedly possessed may lead to more satisfactory, though still imperfect, results.

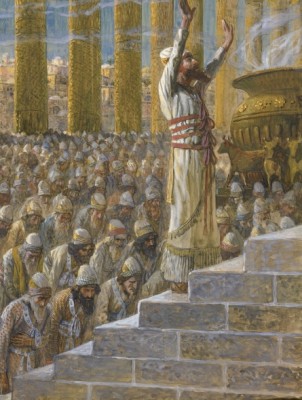

Solomon Builds the Great Temple, featuring a series of excerpts selected from History of the Jews by Henry Hart Milman published in 1829.

Previously in Solomon Builds the Great Temple. Now we continue.

Time: 953 BC

Place: Jerusalem

Pubic domain image from Wikipedia.

Though the chief magnificence of Solomon was lavished on the Temple of God, yet the sumptuous palaces which he erected for his own residence display an opulence and profusion which may vie with the older monarchs of Egypt or Assyria. The great palace stood in Jerusalem; it occupied thirteen years in building. A causeway bridged the deep ravine, and leading directly to the Temple, united the part either of Acra or Sion,on which the palace stood, with Mount Moriah.

In this palace was a vast hall for public business, from its cedar pillars called the House of the Forest of Lebanon. It was 175 feet long, half that measurement in width, above 50 feet high; four rows of cedar columns supported a roof made of beams of the same wood; there were three rows of windows on each side facing each other. Besides this great hall, there were two others, called porches, of smaller dimensions, in one of which the throne of justice was placed. The harem, or women’s apartments, adjoined to these buildings; with other piles of vast extent for different purposes, particularly, if we may credit Josephus, a great banqueting hall.

The same author informs us that the whole was surrounded with spacious and luxuriant gardens, and adds a less credible fact, ornamented with sculptures and paintings. Another palace was built in a romantic part of the country in the valleys at the foot of Lebanon for his wife, the daughter of the king of Egypt; in the luxurious gardens of which we may lay the scene of that poetical epithalamium,[7] or collection of Idyls, the Song of Solomon. [8] The splendid works of Solomon were not confined to royal magnificence and display; they condescended to usefulness. To Solomon are traced at least the first channels and courses of the natural and artificial water supply which has always enabled Jerusalem to maintain its thousands of worshippers at different periods, and to endure long and obstinate sieges. [9]

The descriptions in the Greek writers of the Persian courts in Susa and Ecbatana; the tales of the early travelers in the East about the kings of Samarkand or Cathay; and even the imagination of the Oriental romancers and poets, have scarcely conceived a more splendid page than Solomon, seated on his throne of ivory, receiving the homage of distant princes who came to admire his magnificence, and put to the test his noted wisdom.[10] This throne was of pure ivory, covered with gold; six steps led up to the seat, and on each side of the steps stood twelve lions.

All the vessels of his palace were of pure gold, silver was thought too mean: his armory was furnished with gold; two hundred targets and three hundred shields of beaten gold were suspended in the house of Lebanon. Josephus mentions a body of archers who escorted him from the city to his country palace, clad in dresses of Tyrian purple, and their hair powdered with gold dust. But enormous as this wealth appears, the statement of his expenditure on the Temple, and of his annual revenue, so passes all credibility, that any attempt at forming a calculation on the uncertain data we possess may at once be abandoned as a hopeless task. No better proof can be given of the uncertainty of our authorities, of our imperfect knowledge of the Hebrew weights of money, and, above all, of our total ignorance of the relative value which the precious metals bore to the commodities of life, than the estimate, made by Dr. Prideaux, of the treasures left by David, amounting to eight hundred millions, nearly the capital of our national debt.

Our inquiry into the sources of the vast wealth which Solomon undoubtedly possessed may lead to more satisfactory, though still imperfect, results. The treasures of David were accumulated rather by conquest than by traffic. Some of the nations he subdued, particularly the Edomites, were wealthy. All the tribes seem to have worn a great deal of gold and silver in their ornaments and their armor; their idols were often of gold, and the treasuries of their temples perhaps contained considerable wealth. But during the reign of Solomon almost the whole commerce of the world passed into his territories. The treaty with Tyre was of the utmost importance: nor is there any instance in which two neighboring nations so clearly saw, and so steadily pursued, without jealousy or mistrust, their mutual and inseparable interests.[11]

On one occasion only, when Solomon presented to Hiram twenty inland cities which he had conquered, Hiram expressed great dissatisfaction, and called the territory by the opprobrious name of Cabul. The Tyrian had perhaps cast a wistful eye on the noble bay and harbor of Acco, or Ptolemais, which the prudent Hebrew either would not, or could not–since it was part of the promised land–dissever from his dominions. So strict was the confederacy, that Tyre may be considered the port of Palestine, Palestine the granary of Tyre. Tyre furnished the shipbuilders and mariners; the fruitful plains of Palestine victualledthe fleets, and supplied the manufacturers and merchants of the Phoenician league with all the necessaries of life.[12]

Footnotes:

Footnote 7: I here assume that the Song of Solomon was an epithalamium. I enter not into the interminable controversy as to the literal or allegorical or spiritual meaning of this poem, nor into that of its age. A very particular though succinct account of all these theories, ancient and modern, may be found in a work by Dr. Ginsberg. I confess that Dr. Ginsberg’s theory, which is rather tinged with the virtuous sentimentality of the modern novel, seems to me singularly outof harmony with the Oriental and ancient character of the poem. It is adopted, however, though modified, by M. Rénan.

Footnote 8: According to Ewald, the ivory tower in this poem wasraised in one of these beautiful “pleasances,” in the Anti-Libanus,looking toward Hamath.

Footnote 9: Ewald: Geschichte, iii., pp. 62-68; a very remarkable and valuable passage.

Footnote 10: Compare the great Mogul’s throne, in Tavernier; that of the King of Persia, in Morier.

Footnote 11: The very learned work of Movers, Die Phönizier (Bonn,1841, Berlin, 1849) contains everything which true German industry and comprehensiveness can accumulate about this people. Movers, though in such an inquiry conjecture is inevitable, is neither so bold, so arbitrary, nor so dogmatic in his conjectures as many of his contemporaries. See on Hiram, ii. 326 et seq. Movers is disposed to appreciate as of high value the fragments preserved in Josephus of the Phoenician histories of Menander and Dios. Mr. Kenrick’s Phoenicia may also be consulted with advantage.]

Footnote 12: To a late period Tyre and Sidon were mostly dependent on Palestine for their supply of grain. The inhabitants of these cities desired peace with Herod (Agrippa) because their country was nourished by the king’s country (Acts xii., 20).

| <—Previous | Master List |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.