One small tin canister, about fifteen inches square, was filled with spare shirts, trousers, and shoes, to be used when we reached civilized life.

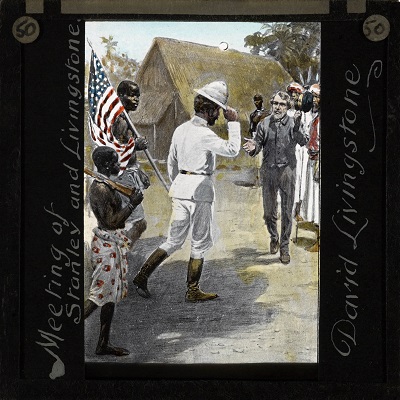

Continuing Livingstone’s African Discoveries,

our selection from David Livingstone by Thomas Hughes published in 1889. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in 3.5 easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Livingstone’s African Discoveries.

Time: 1853-1854

Place: Central Africa

Public domain image from Wikipedia

The journey to Linyanti by the new route was very trying. Part of the country was flooded, and they were wading all day, and forcing their way through reeds with sharp edges “with hands all raw and bloody.” “On emerging from the swamps,” says Livingstone, “when walking before the wagon in the morning twilight, I observed a lioness about fifty yards from me in the squatting way they walk when going to spring. She was followed by a very large lion, but seeing the wagon she turned back.”

It required all his tact to prevent guides and servants from deserting. Everyone but himself was attacked by fever. “I would like,” says his journal, “to devote a portion of my life to the discovery of a remedy for that terrible disease, the African fever. I would go into the parts where it prevails most and try to discover if the natives have a remedy for it. I must make many inquiries of the river people in this quarter.” Again in another key: “Am I on my way to die in Sebituane’s country? Have I seen the last of my wife and children, leaving this fair world and knowing so little of it?”

February 4, 1853: “I am spared in health while all the company have been attacked by fever. If God has accepted my service, my life is charmed till my work is done. When that is finished, some simple thing will give me my quietus. Death is a glorious event to one going to Jesus.”

Their progress was tedious beyond all precedent. “We dug out several wells, and each time had to wait a day or two till enough water flowed in for our cattle to quench their thirst.”

At last, however, at the end of May, he reached the Chobe River and was again among his favorite Makololo. “He has dropped from the clouds,” the first of them said. They took the wagon to pieces and carried it across on canoes lashed together, while they themselves swam and dived among the oxen “more like alligators than men.” Sekeletu, son of Sebituane, was now chief, his elder sister Mamochishane having resigned in disgust at the number of husbands she had to maintain as chieftainess. Poor Mamochishane! After a short reign of a few months she had risen in the assembly and “addressed her brother with a womanly gush of tears. ‘I have been a chief only because my father wished it. I would always have preferred to be married and have a family like other women. You, Sekeletu, must be chief, and build up our father’s house.'”

On November 11, 1853, he left Linyanti, and arrived at Loanda on May 31, 1854. The first stages of the journey were to be by water, and Sekeletu accompanied him to the Chobe, where he was to embark. They crossed five branches before reaching the main stream, a wide and deep river full of hippopotami. “The chief lent me his own canoe, and as it was broader than usual I could turn about in it with ease. I had three muskets for my people, and a rifle and double-barrelled shotgun for myself. My ammunition was distributed through the luggage, that we might not be left without a supply. Our chief hopes for food were in our guns. I carried twenty pounds of beads worth forty shillings, a few biscuits, a few pounds of tea and sugar, and about twenty pounds of coffee. One small tin canister, about fifteen inches square, was filled with spare shirts, trousers, and shoes, to be used when we reached civilized life, another of the same size was stored with medicines, a third with books, and a fourth with a magic lantern, which we found of much service. The sextant and other instruments were carried apart. A bag contained the clothes we expected to wear out in the journey, which, with a small tent just sufficient to sleep in, a sheepskin mantle as a blanket, and a horse rug as a bed, completed my equipment. An array of baggage would have probably excited the cupidity of the tribes through whose country we wished to pass.”

The voyage up the Chobe, and the Zambesi after the junction of those rivers, was prosperous but slow, in consequence of stoppages opposite villages. “My man Pitsane knew of the generous orders of Sekeletu, and was not disposed to allow them remain a dead letter.” In the rapids, “the men leaped into the water without the least hesitation to save the canoes from being dashed against the obstructions or caught in eddies. They must never be allowed to come broadside to the stream, for being flat-bottomed they would at once be capsized and everything in them lost.” When free from fever he was delighted to note the numbers of birds, several of them unknown, which swarmed on the river and its banks, all carefully noted in his journal. One extract must suffice here: “Whenever we step on shore a species of plover, a plaguy sort of public-spirited individual, follows, flying overhead, and is most persevering in its attempts to give warning to all animals to flee from the approaching danger.”

But he was already weak with fever; was seized with giddiness whenever he looked up quickly, and, if he could not catch hold of some support, fell heavily — a bad omen for his chance of passing through the unknown country ahead — but his purpose never faltered for a moment. On January 1, 1854, he was still on the river, but getting beyond Sekeletu’s territory and allies, to a region of dense forest, in the open glades of which dwelt the Balonda, a powerful tribe, whose relations with the Makololo were precarious. Each was inclined to raid on the other since the Mambari and Portuguese half-castes had appeared with Manchester goods. These excited the intense wonder and cupidity of both nations. They listened to the story of cotton-mills as fairy dreams, exclaiming: “How can iron spin, weave, and print? Truly ye are gods!” and were already inclined to steal their neighbors’ children — those of their own tribe they never sold at this time — to obtain these wonders out of the sea.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

David Livingstone begins here. Thomas Hughes begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.