This series has six easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: His First Journey.

Introduction

Although Africa, the second largest continent, has figured in history from ancient times, it has been the least known to the outside world. The ancient seats of African civilization were confined to the northern parts of the continent. The Phoenicians are said to have circumnavigated Africa as early as the seventh century BC. In the middle of the fifteenth century AD the Portuguese explored much of the coastline, and in 1497 Vasco da Gama passed the Cape of Good Hope. But no modern explorations of the interior are known to have been made until the latter part of the eighteenth century. Since James Bruce, the Scottish traveler, explored the Nile Valley in 1768, more than thirty others have distinguished themselves by their discoveries on the African continent.

None of Livingstone’s predecessors equaled the achievements of this Scottish missionary and explorer, who combined with his zeal in the cause of religion and humanity a spirit of investigation and adventure that made him also the servant of science, the “advance-agent” of discovery, settlement, and civilization. These are at last bringing the “Dark Continent” into the light of a new day that begins to dawn in the remotest corners of the earth.

David Livingstone was born near Glasgow, Scotland, March 19, 1813, and he died in Central Africa April 30, 1873. After he had been admitted to the medical profession and had studied theology, he decided to join Robert Moffat, the celebrated missionary, in Africa. Livingstone arrived at Cape Town in 1840, and soon moved toward the interior. He spent sixteen years in Africa, engaged in medical and missionary labors and in making his famous and most useful explorations of the country. His own account of the beginnings of his work, taken from his Missionary Travels, shows the sincere and simple spirit of the man, and his natural powers of observation and description are seen in his own story of his first important discovery, that of Lake Ngami. The narrative of Thomas Hughes, the well-known English author, whose favorite subjects were manly men and their characteristic deeds, follows the explorer on the first of his famous journeys in the Zambesi Basin.

The selections are from:

- Logs by David Livingstone.

- David Livingstone by Thomas Hughes published in 1889.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. There’s 2.5 installments by David Livingstone and 3.5 installments by Thomas Hughes.

We begin with David Livingstone.

Time: 1840

Place: Central Africa

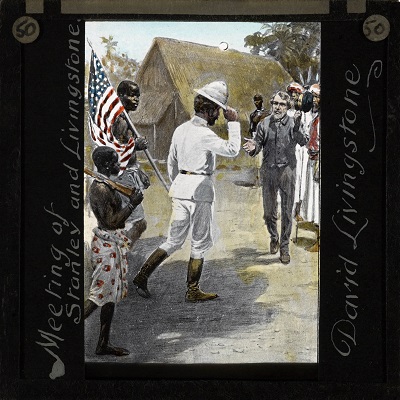

Public domain image from Wikipedia

I embarked for Africa in 1840, and, after a voyage of three months, reached Cape Town. Spending but a short time there, I started for the interior by going round to Algoa Bay, and soon proceeded inland, and spent the following sixteen years of my life, namely, from 1840 to 1856, in medical and missionary labors there without cost to the inhabitants.

The general instructions I received from the directors of the London Missionary Society led me, as soon as I reached Kuruman or Lattakoo, then their farthest inland station from the Cape, to turn my attention to the north. Without waiting longer at Kuruman than was necessary to recruit the oxen, which were pretty well tired by the long journey from Algoa Bay, I proceeded, in company with another missionary, to the Bechuana or Bakwain country, and found Sechele, with his tribe, located at Shokuane. We shortly afterward retraced our steps to Kuruman; but as the objects in view were by no means to be attained by a temporary excursion of this sort, I determined to make a fresh start into the interior as soon as possible. Accordingly, after resting three months at Kuruman, which is a kind of head station in the country, I returned to a spot about fifteen miles south of Shokuane, called Lepelole (now Litubaruba). Here, in order to obtain an accurate knowledge of the language, I cut myself off from all European society for about six months, and gained by this ordeal an insight into the habits, ways of thinking, laws, and language of that section of the Bechuanas called Bakwains, which has proved of incalculable advantage in my intercourse with them ever since.

In this second journey to Lepelole — so called from a cavern of that name — I began preparations for a settlement by making a canal to irrigate gardens from a stream, then flowing copiously, but now quite dry. When these preparations were well advanced I went northward to visit the Bakaa and Bamangwato, and the Makalaka, living between 22° and 23° south latitude. The Bakaa Mountains had been visited before by a trader, who, with his people, all perished from fever. In going round the northern part of these basaltic hills, near Letloche, I was only ten days distant from the lower part of the Zouga, which passed by the same name as Lake Ngami; and I might then (in 1842) have discovered that lake, had discovery alone been my object. Most of this journey beyond Shokuane was performed on foot, in consequence of the draught oxen having become sick. Some of my companions who had recently joined us, and did not know that I understood a little of their speech, were overheard by me discussing my appearance and powers: “He is not strong; he is quite slim, and only appears stout because he puts himself into those bags [trousers]; he will soon knock up.” This caused my Highland blood to rise, and made me despise the fatigue of keeping them all at the top of their speed for days together, till I heard them expressing proper opinions of my pedestrian powers.

Returning to Kuruman, in order to bring my luggage to our proposed settlement, I was followed by the news that the tribe of Bakwains, who had shown themselves so friendly toward me, had been driven from Lepelole by the Barolongs, so that my prospects for the time of forming a settlement there were at an end. One of those periodical outbreaks of war, which seem to have occurred from time immemorial, for the possession of cattle, had burst forth in the land, and had so changed the relations of the tribes to each other that I was obliged to set out anew to look for a suitable locality for a mission-station.

In going north again a comet blazed on our sight, exciting the wonder of every tribe we visited. That of 1816 had been followed by an irruption of the Matabele, the most cruel enemies the Bechuanas ever knew, and this they thought might portend something as bad, or it might only foreshadow the death of some great chief. On this subject of comets I knew little more than they did themselves, but I had that confidence in a kind overruling Providence which makes such a difference between Christians and both the ancient and modern heathen.

As some of the Bamangwato people had accompanied me to Kuruman, I was obliged to restore them and their goods to their chief Sekomi. This made a journey to the residence of that chief again necessary, and, for the first time, I performed a distance of some hundred miles on oxback.

Returning toward Kuruman, I selected the beautiful valley of Mabotsa (latitude 25° 14′ south, longitude 26° 30′) as the site of a missionary-station, and thither I removed in 1843. Here an occurrence took place concerning which I have frequently been questioned in England, and which, but for the importunities of friends, I meant to have kept in store to tell my children when in my dotage. The Bakatla of the village Mabotsa were much troubled by lions, which leaped into the cattle-pens by night and destroyed their cows. They even attacked the herds in open day. This was so unusual an occurrence that the people believed they were bewitched — “given,” as they said, “into the power of the lions by a neighboring tribe.” They went at once to attack the animals, but, being rather a cowardly people compared to Bechuanas in general on such occasions, they returned without killing any.

It is well known that if one of a troop of lions is killed, the others take the hint and leave that part of the country. So the next time the herds were attacked I went with the people in order to encourage them to rid themselves of the annoyance by destroying one of the marauders.

| Master List | Next—> |

Thomas Hughes begins here.

More information here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.