The acceptance by Persia of these demands meant, of course, a virtual cession of her sovereignty to Russia and Great Britain. It should be noted, also, that in this Russian ultimatum the name of the British government was freely used, although the British minister took no part in the presentation of the same.

Featuring a series of excerpts selected from The Strangling of Persia by W. Morgan Shuster published in 1912.

Previously in The Strangling of Persia.

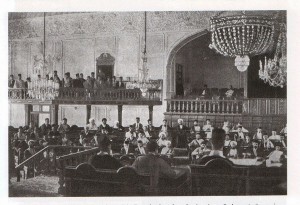

Time: 1911

Place: Teheran

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

On hearing this, I wrote and telegraphed to my friend, M. Poklewski-Koziell, the Russian minister, calling his attention to the outrageous actions of his Consul-General, M. Pokhitanow, and asking the minister to give orders to prevent any further unpleasantness on the following day, when I would again execute the government’s order. The next day I sent a force of one hundred gendarmes in charge of two American Treasury officials, and the order was executed.

Two hours after we were in peaceable possession of the property, the same two Russian vice-consuls drove up to the gate and began insulting and abusing the Persian Treasury guards, endeavoring, of course, to provoke the gendarmes into some act against them. In other words, finding that they had lost in the matter of retaining possession of the property, these Russian officials deliberately sought to provoke my gendarmes into something that they could construe as an affront to Russian consular authority. The men, however, had received such strict and repeated instructions that they refused even to answer. They paid no attention to the taunts and abuse of these two dignified Russian officials, who thereupon drove off and perjured themselves to the effect that they had been affronted–in other words, that the incident which they had gone there to provoke actually had occurred. These false statements were reported to St. Petersburg by M. Pokhitanow independently of his minister, who, I have the strongest reason to believe, entirely disavowed the Consul-General’s actions. The Russian government thereupon publicly discredited its minister and demanded from the Persian government an immediate apology for something that had never occurred. The apology, after some hesitation, was made on the advice of the British government. It was hoped that this evident self-abasement by Persia would appease even the Russian bureaucracy.

But it now seems that a compliance with Russia’s demand was exactly what was not desired by her, since it removed all possible pretext for taking more drastic steps against Persia’s national existence. Hence, at the very moment when the Persian Foreign Minister, in full uniform, was at the Russian legation complying with this first ultimatum, based, as it was, on absolutely false reports, the St. Petersburg cabinet was formulating new and even more unjust and absurd demands, which, as some of the public know, have resulted in the expulsion of the fifteen American finance officials and in the destruction of the last vestiges of constitutional government in the empire of Cyrus and Darius.

Russia called for my immediate dismissal from the post of Treasurer-General; she required that my fourteen American assistants already in Persia should be subject to the approval of the British and Russian legations at Teheran; that all other foreign officials in future employed by Persia be subjected to the approval of those two legations; that a large indemnity should be paid to Russia for the expense of moving her troops into Persia to hasten the acceptance of these two ultimatums; and that all other questions between Russia and Persia should be settled to the satisfaction of the former.

The acceptance by Persia of these demands meant, of course, a virtual cession of her sovereignty to Russia and Great Britain. It should be noted, also, that in this Russian ultimatum the name of the British government was freely used, although the British minister took no part in the presentation of the same. Sir Edward Grey was subsequently asked in the British Parliament as to this point, and explained, in effect, that he agreed with the Russian demands, with the possible exception of the indemnity.

The Russian minister informed the Persian Government that this ultimatum was based on the following two grounds: First, that I had appointed a certain Mr. Lecoffre, a British subject, to be a tax collector in the Russian sphere of influence; and, second, that I had caused to be printed and circulated in Persia a translation into Persian of my letter to the London Times of October 21, 1911, thereby greatly injuring Russian influence in northern Persia. These grounds might be classified as “unimportant, if true.” The truth is, however, that they are both well known to have been utterly unfounded in fact. I did not appoint Mr. Lecoffre, a British subject, to a financial post in northern Persia. I found him in the Finance Department at Teheran (the capital, which is in the so-called Russian sphere) when I arrived there last May, and he had been occupying an important position there for nearly two years, without the slightest objection ever having been raised by the Russian Government. I proposed to transfer him to a somewhat less important position, but one in which I thought he could be of greater service.

As to the second ground or pretext, in effect, that I had caused to be printed and circulated a Persian translation of my letter to the “Times”, it was simply false. It was well known to be false – so well known, in fact, that a newspaper in Teheran, the “Tamadun” (“Civilization”) which did print it and circulate it, publicly admitted the fact the minute they heard that I was charged by Russia with having done so. So these two at best rather puerile pretexts upon which to base an ultimatum from a powerful nation to a weaker one lacked even the merit of truth.

This second ultimatum, despite all hypocritical attempts made to justify it, fairly stunned the Persian people. Accustomed as they had become in recent years to the high-handed and cynical actions of the St. Petersburg cabinet, they had not looked for such a foul blow as this. They had been realizing dimly that the peace of Europe was being threatened by the open hostility of Germany and England over the Moroccan incident, and that British foreign policy was apparently leaving Russia absolutely free to work her will in Asia, so long, at least, as Russia pretended to acknowledge the. Anglo-Russian entente of 1907; but the Persian people had too much, far too much, confidence in the sacredness of treaty stipulations and the solemnly pledged words of the great Christian nations of the world to imagine that their own whole national existence and liberty could be jeopardized overnight, and on a pretext so shallow and farcical as to excite world-wide ridicule. Their disillusionment came too late. The trap had been unwittingly set by hands that made unexpected moves on the European chessboard, and the Bear’s paw had this time been skilful enough to spring it at the proper moment.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.