In this way the writer found himself in Teheran on the 12th of May last year, having agreed to serve as Treasurer-General of the Persian Empire, and to reorganize and conduct its finances.

Featuring a series of excerpts selected from The Strangling of Persia by W. Morgan Shuster published in 1912.

Previously in The Strangling of Persia.

Time: 1911

Place: Teheran

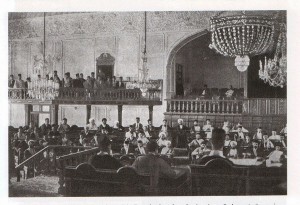

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Persia has given a most perfect example of this struggle toward democracy, and, considering the odds against the nationalist element, the results accomplished have been little short of amazing.

Filled with the desire to perform its task, the Medjlis, or national parliament, had voted in the latter part of 1910 to obtain the services of five American experts to undertake the work of reorganizing Persia’s finances. They applied to the American Government, and through the good offices of our State Department, their legation at Washington was placed in communication with men who were considered suitable for the task. The intervention of the State Department went no further than this, and the Persian Government, like the men finally selected, was told that the nomination by the American Government of suitable financial administrators indicated a mere friendly desire to aid and was of no political significance whatsoever.

The Persians had already tried Belgian and French functionaries and had seen them rapidly become mere Russian political agents or, at best, seen them lapse into a state of dolce far niente. Poor Persia had been sold out so many times in the framing of tariffs and tax laws, in loan transactions and concessions of various kinds that the nationalist government had grown desperate and certainly most distrustful of all foreigners coming from nations within the sphere of European diplomacy. What they sought was a practical administration of their finances in the interest of the Persian people and nation.

In this way the writer found himself in Teheran on the 12th of May last year, having agreed to serve as Treasurer-General of the Persian Empire, and to reorganize and conduct its finances.

It is difficult to describe the Persian political situation existing at that time without going too deeply into history. It is true that in a moment of temporary weakness after her defeat by Japan, Russia had signed a solemn convention with England whereby she engaged herself, as did England, to respect the independence and integrity of Persia. Later, by the stipulations of 1909, these two Powers solemnly agreed to prevent the ex-Shah, Muhammad Ali, from any political agitation against the constitutional government. But, as the world and Persia have seen, a trifle like a treaty or a convention never balks Russia when she has taken the pulse of her possible adversaries and found it weak. What is more painful to Anglo-Saxons is that the British Government has been no better nor more scrupulous of its pledges.

During the first half of July, we began to learn where some of the money was supposed to come from, and we were just beginning to control the government expenditures after a fashion when, on July 18th, late at night, the telegraph brought the news that Muhammad Ali, the ex-Shah, had landed with a small force at Gumesh-Teppeh, a small port on the Caspian, very near the Russian frontier. It was the proverbial bolt from the blue, for while rumors of such a possibility had been rife, most persons believed that Russia would not dare to violate so openly her solemn stipulation signed less than two years before.

PERSIA IS TAKEN UNAWARES

The Persian cabinet at Teheran was panic-stricken, and for ten days there ensued a period of confusion and terror that beggars description. There was no Persian army except on paper. The gendarmerie and police of the city did not number more than eighteen hundred men inadequately armed. The Russian Turcomans on the northeast frontier were reported to be flocking to the ex-Shah’s standard, and it was commonly believed that he would be at the gates of Teheran in a few weeks. This belief was strengthened by the fact that his brother, Prince Salaru’d-Dawla, had entered Persia from the direction of Bagdad and was known to have a large gathering of Kurdish tribesmen ready to march toward Teheran.

After a time, however, reason prevailed and steps were taken to create an army to defend the constitutional government against the invaders. At this time, one of the old chiefs of the Bakhtiyari tribesmen, the Samsamu’s-Saltana, was the prime minister holding the portfolio of war, and he called to arms several thousands of his fighting men, who promptly started for the capital. Ephraim Khan, at that time chief of police of Teheran, was another defender of the constitution who raised a volunteer force, and twice, acting with the Bakhtiyari forces, he signally defeated the troops of the ex-Shah. By September 5th, Muhammad Ali himself was in full flight through northeastern Persia toward the friendly Russian frontier. Whatever chances he may have formerly had were admitted to be gone.

The hound that Russia had unleashed, with his hordes of Turcoman brigands, upon the constitutional government of Persia had been whipped back into his kennel. No one was more surprised than Russia, unless indeed it was the Persians themselves. Russian officials everywhere in Persia had openly predicted an easy victory for Muhammad Ali. They had aided him in a hundred different ways, morally, financially, and by actual armed force.

They still hoped, however, that the forces of Prince Salaru’d-Dawla, which were marching from Hamadan toward Teheran, would take the capital. But on September 28th, the news came that Ephraim Khan, and the Bakhtiyaris had routed the Prince and his army, and the last hope from this source was gone.

In the mean time, another encounter with Russia had occurred. There was at Teheran an officer of the British-Indian army, Major Stokes, who for four years had been military attache to the British Legation. He knew Persia well; read, wrote, and spoke fluently the language and thoroughly understood the habits, customs, and viewpoint of the Persian people. He was the ideal man to assist in the formation of a tax-collecting force under the Treasury, without which there was no hope of collecting the internal taxes throughout the empire. Not only was Major Stokes the ideal man for this work, but he was the only man possessing the necessary qualifications.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.