Today’s installment concludes Chile Captures Lima,

our selection from The War Between Chile and Peru, 1879-1882 by Clements R. Markham published in 1882. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of five thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Chile Captures Lima.

Time: 1881

Place: Lima, Peru

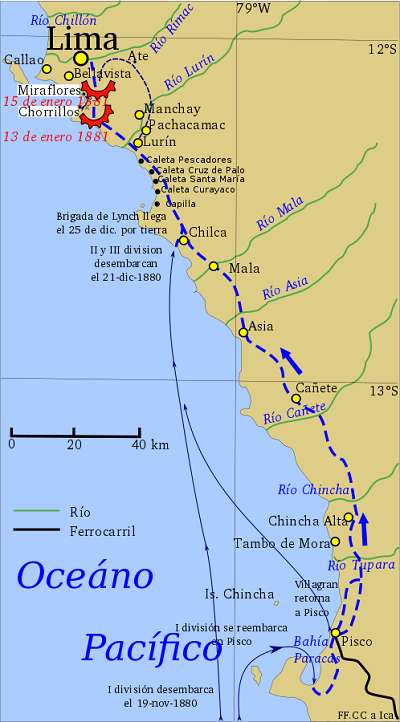

CC BY-SA 4.0 image from Wikipedia

The students and merchants made an attack upon the Chilian first division, supported by the reserves, while the guns of San Bartolome” and San Cristoval kept up a sullen roar in the rear. For a time the vigorous assault of the citizens afforded a gleam of hope, the enemy wavered, their ammunition was failing. But reinforcements came up, and a battery of artillery opened fire from the ridge of Huaca Juliana. The defenders were forced back, and at last the redoubts were carried at the point of the bayonet. They were filled with dead, young lads from the desk and the counter, many well-dressed men of fashion, and students. One student had been wiling away the hours before the battle by reading a story of lives of brave endurance. Amid the dead was a volume of letters from the martyr Jesuits in Japan. In one place there was a heap of Italian youths, volunteers who would not see their Peruvian friends go forth to fight without helping them. They were lads of the “Garibaldi Legion,” as was testified by the legend on their caps. Most pathetic was the wall of youthful dead, which the invading soldiery must trample over before the city could be reached.

There were old men as well as young among the heroic dead. Dr. Pino, a learned judge of the Superior Court at Puno, aged sixty; Senor Ugariza, secretary of the Lima Chamber of Commerce; Senor Los Heros, the chief clerk of the Foreign Office; the diplomatist Marquez, brother of the poet; two editors; members of Congress, magistrates, wealthy landed proprietors, were all lying dead, after fighting in defense of their country’s capital. Ricardo Palma, the charming writer of historical anecdotes, was fighting, though fortunately he escaped with life. But his house, with a priceless library of American works, was destroyed.

At 4.45 p.m. the defending fire was slackening. Resistance was now concentrated at the central part of the line near Miraflores. At 5.35 p.m. the center redoubt was carried at the point of the bayonet, and by six o’clock the fell work was done. The defense had been bravely maintained nearly four hours.

The very night before the battle saw the arrival of an important reinforcement. The redoubtable Morochuco Indians, having at length received arms, came down by forced marches just in time to share in the honors of the day. Their chief, named Miola, was among the slain, a fact which the Chilians will have cause to remember, if their predatory incursions ever bring them into the neighborhood of the wild Andes of Cangallo. The aged General Vargas Machuca, a hero of the Battle of Pichincha, now past eighty, was wounded. Generals Silva and Segura and Colonel Caceres received five honorable scars; and the young son of the brave Iglesias was killed.

The Supreme Chief Pierola rode off the field when all was lost, and retired to the little town of Canta in the mountains, accompanied or followed by General Buendia, Colonel Suarez, and the secretary, Captain Garcia y Garcia. Pierola appointed Admiral Montero to the direction of affairs in the northern departments, and he made his way along the coast, by Huacho to Truxillo, and thence to Caxamarca. Colonel Echenique received charge of the central departments, while Doctor Solar took command at Arcquipa. Don Rufino Torico was left in charge at Lima.

Another tale of two thousand dead swelled the number of mourners in Lima. At 6.45 p.m. Miraflores was in flames. The savage victors sacked and burnt all the pleasant country houses and destroyed the lovely gardens. This once charming retreat shared the fate of Chorrillos and Barranco.

Lima, the great city, would have shared the fate of Chorrillos and Miraflores if the Chilians had had their way. Its rescue from destruction is due to the firm stand made by the British Minister, Sir Spencer St. John, backed by the material power and calm resolve of the English and the French admirals. On the 16th Don Rufino Torico, the Municipal Alcalde of Lima, made a formal agreement with the Chilian general to surrender the unfortunate city.

During the night the dangerous classes ran riot; the Chinese quarter was gutted, and if the foreigners had not formed an efficient volunteer corps, the whole place might have been sacked. On the 17th the Chilian troops took possession of Lima. General Baquedano, with his headquarters staff, made his entrance on the following day, and established himself in the palace.

In the two battles the Chilian losses were reported to be five thousand four hundred forty-three, of whom one thousand two hundred ninety-nine were killed, and four thousand one hundred forty-four wounded. The Peruvians lost far more heavily, the proportion between killed and wounded telling, as usual, a tale of savage butchery.

After a gallant and well-conducted naval effort, and after three hard- fought campaigns, the coast of Peru was conquered, and the capital was occupied by the enemy. The unfortunate people had to drink the cup of sorrow and humiliation to the dregs. Although the Peruvian and Chilian governing classes are one people, having a common ancestry, often bound together by the ties of kindred, with the same religion, speaking the same language, with the same history until recent years, and the same traditions, yet the conquerors showed no relenting, no wish to soften the calamity. Not only were they harsh and exacting, but they pushed their power of appropriating and confiscating to unprecedented lengths. Blackmail was levied upon private citizens, with threats that their houses would be destroyed if the demands were not immediately met. Public property unconnected with the war was seized. The public library of Lima was carried off. Even the picture, by Monteros, of the obsequies of Atahualpa was stolen. In all this is seen the demoralizing effect of a policy of military glory and conquest.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Chile Captures Lima by Clements R. Markham from his book The War Between Chile and Peru, 1879-1882 published in 1882. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Chile Captures Lima here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.