Volumes would not contain the bare record of the acts of aggression, deceit, and cruelty which Russian agents have committed against Persian sovereignty and the constitutional government since the deposition of Muhammad Ali in 1909.

Featuring a series of excerpts selected from The Strangling of Persia by W. Morgan Shuster published in 1912.

Previously in The Strangling of Persia.

Time: 1911

Place: Teheran

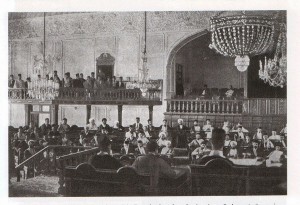

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

December 24th, late in the evening, a message was received from the Persian Acting Governor at Tabriz in which he declared that the Russian troops, which had been stationed in that city since their entry during the siege in 1909, had suddenly started to massacre the inhabitants. Shortly after this the Indo-European telegraph lines stopped working, and all news from Tabriz ceased. It was subsequently stated that the wires had been cut by bullets. Additional Russian troops were immediately started for Tabriz from Julfa, which is some eight miles to the north of the Russian frontier.

The exact way in which the fighting began is not yet clear. The Persian government reports show that a number of Russian soldiers, claiming to be stringing a telephone wire, climbed upon the roof of the Persian police headquarters about ten o’clock at night on December 20th. When challenged by native guards, they replied with shots. Reinforcements were called up by both sides, and serious street fighting broke out early the following morning and continued for several days. The Acting Governor stated in his official reports that the Russian troops indulged in their usual atrocities, killing women and children and hundreds of other noncombatants on the streets and in their homes. There were at the time about 4,000 Russian soldiers, with two batteries of artillery, in and around the city. Nearly I,000 of the fidais (“self-devoted”) of Tabriz took refuge in an old citadel of stone and mud, called the “Ark.” They were without artillery or adequate provisions, and were poorly armed, but it was certain death for one of them to be seen on the streets.

The Russians bombarded the “Ark” for a day or more, killing a large proportion of its defenders. The superior numbers and the artillery of the Russians finally conquered, and there followed a reign of terror during which no Persian’s life or honor was safe. At one time during this period the Russian Minister at Teheran, at the request of the members of the Persian cabinet, who were horror-stricken and in fear of their lives for having made terms with such a barbaric nation, telegraphed to the Russian general in command of the troops at Tabriz, telling him to cease fighting, and that the fidais would receive orders to do likewise, as matters were being arranged at the capital. The gallant general replied that he took his orders from the Viceroy of the Caucasus at Tiflis, and not from any one at Teheran. The massacre went on.

On New Year’s day, which was the 10th of Muharram, a day of great mourning which is held sacred in the Persian religious calendar, the Russian military governor, who had hoisted Russian flags over the government buildings at Tabriz, hung the Sikutu’l-Islam, who was the chief priest of Tabriz, two other priests, and five others, among them several high officials of the Provincial Government. As one British journalist put it, the effect of this outrage on the Persians was that which would be produced on the English people by the hanging of the Archbishop of Canterbury on Good Friday. From this time on, the Russians at Tabriz continued to hang or shoot any Persian whom they chose to consider guilty of the crime of being a “Constitutionalist.” When the fighting there was first reported, a high official of the Foreign Office at St. Petersburg, in an interview to the press, made the statement that Russia would take vengeance into her own hands until the “revolutionary dregs” had been exterminated.

One more significant fact: At the same time that the fighting broke out at Tabriz, the Russian troops at Resht and Enzeli, hundreds of miles away, shot down the Persian police and many inhabitants without warning or provocation of any kind. And the date also happened to be just after the Persian cabinet had definitely informed the Russian Legation that all the demands of Russia’s ultimatum were accepted–a condition which the British Government had publicly assured the Persians would be followed by the withdrawal of the Russian invading forces, and which the Russian Government had officially confirmed, “unless fresh incidents should arise in the mean time to make the retention of the troops advisable.”

I would suggest that the Powers–England and Russia–may think that they thus escape all responsibility for what goes on in Persia, but the world has long since grown familiar with such methods. Mere cant, however seriously put forth in official statements, no longer blinds educated public opinion as to the facts in these acts of international brigandage. The truth is that England and Russia are still playing a hand in the game of medieval diplomacy.

The puerility of talking of Persia having affronted Russian consular officers or of Persia’s Treasurer-General having appointed a British subject to be a tax collector at Tabriz, as the reasons for Russia’s aggressive and brutal policy in Persia, is only too apparent. Volumes would not contain the bare record of the acts of aggression, deceit, and cruelty which Russian agents have committed against Persian sovereignty and the constitutional government since the deposition of Muhammad Ali in 1909.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The Strangling of Persia by W. Morgan Shuster from his book of the same name published in 1912. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.