When the last representative element of the constitutional government, for which so many thousands had fought, suffered, and died, was wiped out in an hour without a drop of blood being shed, the Persian people gave to the world an exhibition of temperance, of moderation, of stern self-restraint, the like of which no other civilized country could show under similar trying circumstances.

Featuring a series of excerpts selected from The Strangling of Persia by W. Morgan Shuster published in 1912.

Previously in The Strangling of Persia.

Time: 1911

Place: Teheran

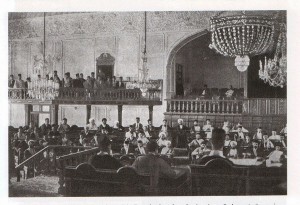

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

One day, the rumor would come that the chief “mullahs” or priests at Nadjef had proclaimed the “holy war” (jihad) against the Russians; on another, that the Russian troops had commenced to shoot up Kasvin on their march to Teheran.

At one time, when rumors were thick that the Medjlis would give in under the threats and attempted bribery which well-known Russian proteges were employing on many of its members, three hundred veiled and black-gowned Persian women, a large proportion with pistols concealed under their skirts or in the folds of their sleeves, marched suddenly to the Parliament grounds and demanded admission to the Chamber. The president of the Medjlis consented to receive a deputation from them. Once admitted into his presence, these honor-loving Persian mothers, wives, and daughters exhibited their weapons, and to show the grim seriousness of their words, they tore aside their veils, and threatened that they would kill their own husbands and sons, and end their own lives, if the deputies failed in their duty to uphold the dignity and the sovereignty of their beloved country.

When neither threats nor bribes availed against the Medjlis, Russia decreed its destruction by force.

In the early afternoon of December 24th, the deposed cabinet, having been themselves duly persuaded to take the step, executed a coup d’état against the Medjlis, and by a demonstration of gendarmes and Bakhtiyari tribesmen, succeeded in expelling all the deputies and employees who were within the Parliament grounds; after which the gates were locked and barred, and a strong detachment of the so-called Royal Regiment left in charge. The deputies were threatened with death if they attempted to return there or to meet in any other spot, and the city of Teheran immediately passed under military control. The self-constituted directoire of seven who accomplished this dubious feat first ascertained that the considerable force of Bakhtiyari tribesmen, some 2,000, who had remained in the capital after the defeat of the ex-Shah’s forces in September last, had been duly “fixed” by the same Russian agencies who had so early succeeded in persuading the members of the ex-cabinet that their true interests lay in siding with Russia. It is impossible to say just what proportions of fear and cupidity decided the members of the deposed cabinet to take the aliens’ side against their country, but both emotions undoubtedly played a part. The premier was one of the leading chiefs or “khans” of the Bakhtiyaris, and another chief was the self-styled Minister of War. These chieftains have always been a strange and changing mixture of mountain patriot and city intriguer–of loyal soldier and mercenary looter. The mercenary instincts, possibly aided by a sense of their own comparative helplessness against Russian Cossacks and artillery, led them to accept the stranger’s gold and fair promises, and they ended their checkered but theretofore relatively honorable careers by selling their country for a small pile of cash and the more alluring promise that the “grand viziership” (i.e., post of Minister of Finance) should be perpetual in their family or clan.

That same afternoon a large number of the “abolished” deputies came to my office. They were men whom I had grown to know well, men of European education, in whose courage, integrity, and patriotism I had the fullest confidence. To them, the unlawful action of their own countrymen was more than a political catastrophe; it was a sacrilege, a profanation, a heinous crime. They came in tears, with broken voices, with murder in their hearts, torn by the doubt as to whether they should kill the members of the directoire and drive out the traitorous tribesmen who had made possible the destruction of the government, or adopt the truly Oriental idea of killing themselves. They asked my advice, and, hesitating somewhat as to whether I should interfere to save the lives of notorious betrayers of their country, I finally persuaded them to do neither the one nor the other. There seemed to be no particular good in assassinating even their treacherous countrymen, as it would only have given color to the pretensions of Russia and England that the Persians were not capable of maintaining order.

AN EXHIBITION OF SELF-RESTRAINT

When the last representative element of the constitutional government, for which so many thousands had fought, suffered, and died, was wiped out in an hour without a drop of blood being shed, the Persian people gave to the world an exhibition of temperance, of moderation, of stern self-restraint, the like of which no other civilized country could show under similar trying circumstances.

The acceptance of Russia’s terms by the Cabinet removed the last pretext for keeping in Northern Persia the 15,000 troops which by that time Russia had assembled there,–at Kasvin, Resht, Enzeli, Tabriz, Khoy, and other points in the so-called Russian sphere. Mons. Poklewski-Koziell, the Russian Minister, had in fact given an equivocal sort of a promise to the effect that “if no fresh incidents arose,” the Russian troops would be withdrawn when Persia accepted the conditions of the ultimatum.

With this in mind, it is interesting to note the truly thorough precautions which were taken by Russia to prevent any such unfortunate necessity as the withdrawal of her troops from coming to pass.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.