From all that remains of proceedings in the Star-chamber, they seem to have been very frequently as iniquitous as they were severe.

Continuing The End of the Star Chamber,

with a selection from Constitutional History of England from the Accession of James II by Henry Hallam published in 1827. This selection is presented in three easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously on The End of the Star Chamber.

Time: 1641

Place: London

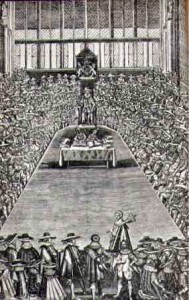

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It is evident that the strong interest of the court in these fines must not only have had a tendency to aggravate the punishment, but to induce sentences of condemnation on inadequate proof. From all that remains of proceedings in the Star-chamber, they seem to have been very frequently as iniquitous as they were severe. In many celebrated instances, the accused party suffered less on the score of any imputed offence than for having provoked the malice of a powerful adversary, or for notorious dissatisfaction with the existing government. Thus Williams, Bishop of Lincoln, once lord-keeper the favorite of King James, the possessor for a season of the power that was turned against him, experienced the rancorous and ungrateful malignity of Laud, who, having been brought forward by Williams into the favor of the court, not only supplanted by his intrigues, and incensed the King’s mind against his benefactor, but harassed his retirement by repeated persecutions. It will sufficiently illustrate the spirit of these times to mention that the sole offence imputed to the Bishop of Lincoln in the last information against him in the Star-chamber was that he had received certain letters from one Osbaldiston, master of Westminster school, wherein some contemptuous nickname was used to denote Laud.

It did not appear that Williams had ever divulged these letters; but it was held that the concealment of a libellous letter was a high misdemeanor. Williams was therefore adjudged to pay five thousand pounds to the King and three thousand to the Archbishop, to be imprisoned during pleasure, and to make a submission; Osbaldiston to pay a still heavier fine, to be deprived of all his benefices, to be imprisoned and make submission, and, moreover, to stand in the pillory before his school in Dean’s yard, with his ears nailed to it. This man had the good fortune to conceal himself; but the Bishop of Lincoln, refusing to make the required apology, lay about three years in the Tower, till released at the beginning of the Long Parliament.

It might detain me too long to dwell particularly on the punishments inflicted by the Court of Star-chamber in this reign. Such historians as have not written in order to palliate the tyranny of Charles, and especially Rushworth, will furnish abundant details, with all those circumstances that portray the barbarous and tyrannical spirit of those who composed that tribunal. Two or three instances are so celebrated that I cannot pass them over. Leighton, a Scots divine, having published an angry libel against the hierarchy, was sentenced to be publicly whipped at Westminster and set in the pillory, to have one side of his nose slit, one ear cut off, and one side of his cheek branded with a hot iron; to have the whole of this repeated the next week at Cheapside, and to suffer perpetual imprisonment in the Fleet. Lilburne, for dispersing pamphlets against the bishops, was whipped from the Fleet prison to Westminster, there set in the pillory, and treated afterward with great cruelty. Prynne, a lawyer of uncommon erudition and a zealous Puritan, had printed a bulky volume, called Histriomastix, full of invectives against the theatre, which he sustained by a profusion of learning. In the course of this he adverted to the appearance of courtesans on the Roman stage, and, by a satirical reference in his index, seemed to range all female actors in the class. The Queen, unfortunately, six weeks after the publication of Prynne’s book, had performed a part in a mask at court. This passage was accordingly dragged to light by the malice of Peter Heylin, a chaplain of Laud, on whom the Archbishop devolved the burden of reading this heavy volume in order to detect its offences.

Heylin, a bigoted enemy of everything Puritanical, and not scrupulous as to veracity, may be suspected of having aggravated, if not misrepresented, the tendency of a book much more tiresome than seditious. Prynne, however, was already obnoxious, and the Star-chamber adjudged him to stand twice in the pillory, to be branded in the forehead, to lose both his ears, to pay a fine of five thousand pounds, and to suffer perpetual imprisonment. The dogged Puritan employed the leisure of a jail in writing a fresh libel against the hierarchy. For this, with two other delinquents of the same class, Burton a divine, and Bastwick a physician, he stood again at the bar of that terrible tribunal. Their demeanor was what the court deemed intolerably contumacious, arising, in fact, from the despair of men who knew that no humiliation would procure them mercy. Prynne lost the remainder of his ears in the pillory; and the punishment was inflicted on them all with extreme and designed cruelty, which they endured, as martyrs always endure suffering, so heroically as to excite a deep impression of sympathy and resentment in the assembled multitude. They were sentenced to perpetual confinement in distant prisons. But their departure from London and their reception on the road were marked by signal expressions of popular regard; and their friends resorting to them even in Launceston, Chester, and Carnarvon castles, whither they were sent, an order of council was made to transport them to the isles of the Channel.

It was the very first act of the Long Parliament to restore these victims of tyranny to their families. Punishments by mutilation, though not quite unknown to the English law, had been of rare occurrence; and thus inflicted on men whose station appeared to render the ignominy of whipping and branding more intolerable, they produced much the same effect as the still greater cruelties of Mary’s reign, in exciting a detestation of that ecclesiastical dominion which protected itself by means so atrocious.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.