This series has five easy 5 minute installments. This first installment: Peru’s City.

Introduction

The war of 1879-1883, waged by Chile against the combined forces of Peru and Bolivia, practically ended with the capture of Lima, the Peruvian capital, although some feeble resistance continued to be offered for more than a year by small bands of the defeated people. The result of the war has been to place Chile in the foremost rank of the South American States. Bolivia, never much more than a half-civilized community, has been shut off entirely from the Pacific coast and almost relegated to the unimportant obscurity of a mountain wilderness. As for Peru, she has fallen from a position of culture and power but little inferior to that of Chile, and has been devastated by such ruin as has thrown her back many years in the march of civilization.

The war originated in a boundary dispute between Chile and Bolivia, and Peru was dragged unwillingly into the fight by the fact that she had a defensive alliance with her mountain neighbor. The Bolivians took no very active part in the contest, but were defeated in a few preliminary encounters, after which they fled to the security of their mountains and watched the result.

Between Peru and Chile the war soon became a naval struggle. Extensive land operations are hardly feasible in a strip of country consisting of thousands of miles of seacoast, backed by an inaccessible mountain range, and interspersed with many leagues of desert. The command of the ocean thus became essential to successful invasion upon either side; and the final destruction of the last of the Peruvian ironclads, as narrated in a previous article, left Chile free to carry her troops up and down the coast, landing them at will to plunder and destroy. To this method of harassment she devoted her energies with a cruelty hardly useful and a vandalism wholly barbaric. Finally, late in 1880, Peru having refused in desperation to consent to her foe’s harsh terms of peace, the entire Chilian army was dispatched to the attack upon Lima, which is here described.

This selection is from The War Between Chile and Peru, 1879-1882 by Clements R. Markham published in 1882. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Clements R. Markham was (1830-1916) was an English geographer, explorer, and writer. He was President of the Royal Geographic Society for twelve years.

Time: 1881

Place: Lima, Peru

CC BY-SA 4.0 image from Wikipedia

Lima, the city of kings, the wealthy and prosperous capital of Peru, was now threatened with all the horrors of war. Her long line of houses and lofty towers are visible from the sea, with rocky mountains rising immediately in the rear, until lost in the clouds; and a fertile plain extends in front down to the forts and shipping of Callao, which form a foreground.

In 1880 the population of Lima was estimated at one hundred thousand, but this is certainly below the truth. There were fifteen thousand foreigners alone, including a large colony of Italians. The upper classes were gay and pleasure- seeking, like their predecessors in the days of the viceroys. Many families had been ennobled in colonial times; some were of illustrious descent. The majority probably derived their origin from Andalusia or Castile, yet the numerous Basque names show that nearly as many were from the freedom-loving sister-provinces of Cantabria. But there was quite as much business as pleasure on the banks of the Rimac. The city contained many foreign merchants’ houses, also numerous contractors and speculators, French and Italian shops, and busy mechanics. It abounded, too, in churches and convents, as well as in taverns, idlers, and vice. It was a great and busy city, throbbing with thousands of different aims, desires, and manifold interests — a mighty and complicated machine, not to be broken and mangled without heavy guilt resting on the destroyer.

That destroyer was almost at the city gates. The gay and thoughtless youths, the workmen and the idlers, the students and mechanics, all were suddenly called upon to face death in defense of the capital — all that could bear arms — there could be no exceptions. The national army was destroyed, and the conquerors were landing on the coast.

Nicolas de Pierola saw the danger, and strove heart and soul to avert it. He was full of hope and ardor — mad, bragging arrogance his enemies called it. But he did not despair of his country in her great need, and the survivors of the death-dealing campaigns rallied round him. But how few! How many brave ones were lost forever — the flower of the army. If two thousand of the veterans could have gathered round the few surviving chiefs, it would be all; but there were barely as many as that. A decree was issued ordering every male resident in Lima, between the ages of sixteen and sixty, of all professions, trades, and callings, to join the army. But decrees alone cannot make an army. Six months is not sufficient time in which to create veteran soldiers. Hundreds might be sent to the sand-hills to fight bravely and to die, but they were only patriots, not soldiers.

When it became certain that the invading army would land to the south of Lima, the advisers of Pierola decided upon forming a line of defense by the arid sandy hills on the verge of the desert, extending from the Morro Solar and Chorrillos to the mountains on the east. The time was very short, and it was impossible to do more than dig a few ditches, throw breastworks across the roads and in front of the main positions, and place the guns. The line was of immense extent, at least six miles long, and was broken by gullies and by barren hills about one hundred feet high. The Morro Solar is six hundred feet above the sea, with Chorrillos at its northern base.

This outer line of defense was about ten miles from Lima, and the hastily drilled people of the capital, with many recruits from the interior, but a pitifully small sprinkling of trained soldiers, were encamped there among the sand-hills, under the leadership of the indefatigable and undaunted Pierola.

A second line of defenses was prepared, which passed just outside of Miraflores, only six miles from Lima, and was at least four miles long. So, the preparations were completed. There were double lines of defenses, several miles long; just as if effective artillery were to be mounted and served and a disciplined army were to hold the positions. There were many unserviceable guns, and a few brave hearts, a few good men and true, a few thousands of gallant young fellows who were not soldiers, and a great rabble. It was right that a stand should be made. The capital must not fall without a blow struck in its defense.

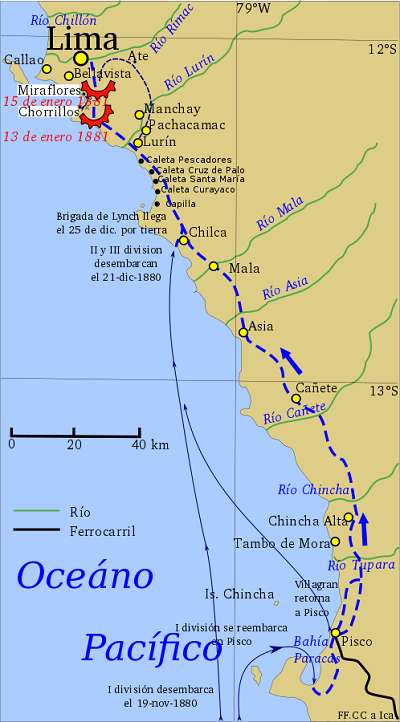

The first division of the Chilian army, under General Lynch, landed at Pisco, marched northward on December 13th to form a junction with the rest of the forces which debarked at Curayaco, a point nearer Lima. There were no serious difficulties in the march from this valley, and a small steamer, the Gaviota, kept on a parallel line with the column of troops. The first march was to Tambo de Mora, at the mouth of the river Chincha, where the Gaviota landed fresh bread for the men. A party went on in advance, opening wells at which the soldiers could fill their cara- mayolas (“water-bottles”).

Lynch’s division marched in a leisurely way, resting a day at Chincha. In crossing the strip of desert between Chincha and Canete there was an attack on the outposts by some patriotic skirmishers under cover of the morning mist; and on the 19th the broad and fertile Vale of Canete was at the mercy of the invaders.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information on Chile Captures Lima here and here and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.