The religious life of Akbar had undergone a vast change. He was testing religion by morality and reason. His faith in Islam was fading away.”

Continuing Akbar Establishes the Moghul Empire In India,

our selection from The History of India: Mogul Empire by James Talboys Wheeler published in 1881. The selection is presented in six easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Akbar Establishes the Moghul Empire In India.

Time: 1556

Place: Lahore, India

By this time Akbar held the Ulama in small esteem. He was growing sceptical of their religion. He had listened to the history of the caliphate; he yearned toward Ali and his family; he became in heart a Shiah. Already he may have doubted Mohammad and the Koran. Still he was outwardly a Muslem. His object now was to overthrow the Ulama altogether; to become himself the supreme spiritual head, the pope or caliph of Islam. Abul Fazl was laboring to invest him with the same authority. He mooted the question one Thursday evening. He raised a storm of opposition; for this he was prepared. He had started the idea; he exerted all his tact and skill to carry it out.

The debates proved that there were differences of opinion among the Ulama. Abul Fazl urged that there were differences of opinion between the highest Muslem authorities; between those who were accepted as infallible, and were known as Mujtahids. He thus inserted the thin edge of the wedge. He proposed that when the Mujtahids disagreed, the decision should be left to the Padishah. Weeks and months passed away in these discussions. Nothing could be said against the measure excepting that it would prove offensive to the Padishah.

Meantime a document was drawn up in the names of the chief men among the Ulama. It gave the Padishah the power of deciding between the conflicting authorities. It gave him the still more dangerous power of issuing fresh decrees, provided they were in accordance with some verse of the Koran and were manifestly for the benefit of the people. The document was in the handwriting of Sheik Mubarak; Abul Fazl, Abdul Faiz, and probably Akbar himself had each a hand in the composition. The chief men among the Ulama were required to sign it. Perhaps if they had been priests or divines they might have resisted to the last. But they were magistrates and judges; their posts and emoluments were in danger. In the end they signed it in sheer desperation. From that day the power of the Ulama was gone; they had abdicated their authority to the padishah; they became mere ciphers in Islam. A worse lot befell their leaders. The head of the Ulama and the obnoxious chief justice were removed from their posts and forced to go to Mecca. The breaking up of the Ulama is an epoch in history of Muslem India. The Ulama may have been ignorant and bigoted; they may have sought to keep religions and the government of the empire within the narrow grooves of orthodoxy. Nevertheless, they had played an important part throughout Muslem rule. As exponents of the law of Mohammad they had often proved a salutary check upon despotism of the sovereign. They had forced every minister, governor, and magistrate to respect the fundamental principles of the Koran. They led and controlled public opinion among the Muslem population. They formed the only body in the state that ever ventured to oppose the will of the sovereign.

The Thursday evenings had done their work. Within four years they had broken up the power of the Ulama. Abul Fazl had another project in his brain; it combined the audacity of genius with the mendacity of a courtier. He declared that Akbar was himself the twelfth imam, the lord of the period, who was to reconcile the seventy-two sects of Islam, to regenerate the world, to usher in the millennium. The announcement took the court by surprise. It fitted, however, into current ideas; it paved the way for further assumptions. Akbar grasped the notion with eagerness; it fascinated him for the remainder of his life; it bound him in the closest ties of friendship and confidence with Abul Fazl.

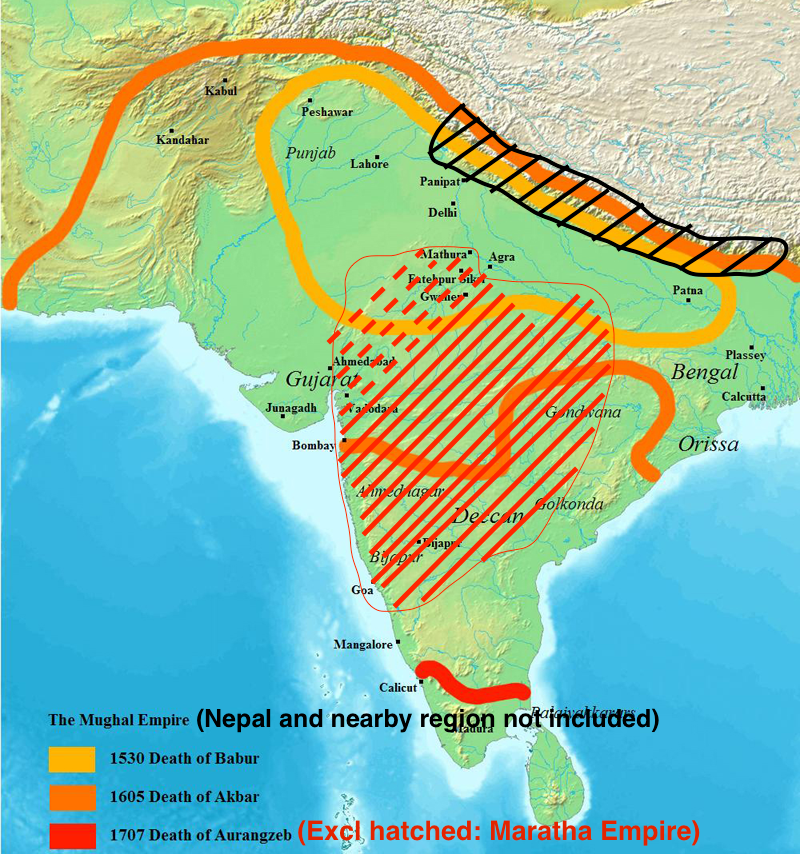

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The religious life of Akbar had undergone a vast change. He was testing religion by morality and reason. His faith in Islam was fading away. Mohammad had married a girl of ten; he had taken another man’s wife; therefore he could not have been a prophet sent by God. Akbar disbelieved the story of his night-journey to heaven. Meantime Akbar was eagerly learning the mysteries of other religions. He entertained Brahmans, Sufis, Parsis, and Christian fathers. He believed in the transmigration of the soul, in the supreme spirit, in the ecstatic reunion of the soul with God, in the deity of fire and the sun. He leaned toward Christianity; he rejected the trinity and incarnation.

The gravitations of Akbar toward Christianity are invested with singular interest. He had been impressed with what he heard of the Portuguese in India; their large ships, impregnable forts, and big guns. He sent a letter to the Portuguese viceroy at Goa inviting Christian fathers to come to his court at Fathpur Sikri and instruct him in the sacred books. The religious world at Goa was thrown into a ferment at the prospect of converting the Great Mogul. Every priest in Goa prayed that he might be sent on the mission. Three fathers were despatched to Fathpur, which was more than twelve hundred miles away. Akbar awaited their arrival with the utmost impatience. He received them with every mark of favor. They delivered their presents, consisting of a polyglot Bible in four languages and the images of Jesus and the Virgin Mary. To their unspeakable delight the Great Mogul placed the Bible on his head and kissed the images. So eager was he for instruction that he spent the whole night in conversation with the fathers. He provided them with lodgings in the precincts of his palace; he permitted them to set up a chapel and altar.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.