So far Akbar had prospered; he had conquered the great highway into the Deccan–Malwa, Khandesh, Berar, and Ahmadnagar. He raised Abul Fazl to the command of four thousand.”

Today’s installment concludes Akbar Establishes the Moghul Empire In India,

our selection from The History of India: Mogul Empire by James Talboys Wheeler published in 1881.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of six thousand words. Congratulations!

Previously in Akbar Establishes the Moghul Empire In India.

Time: 1556

Place: Lahore, India

Abul Fazl departed on his mission. He arrived at Burhanpur, the capital of Khandesh. He soon discovered the luke-warmness of Bahadur Khan, the ruler. He insisted that Bahadur Khan should join him and help the imperial cause. Bahadur Khan was disinclined to help Akbar to conquer the Deccan. He thought to back out by sending rich presents to Abul Fazl. Abul Fazl was too loyal to be bribed; he returned the presents and went alone toward Ahmadnagar.

Meanwhile Amurath was retreating from Ahmadnagar. He encamped in Berar; he drank more deeply than ever; he died very suddenly the very day that Abul Fazl came up. The death of Amurath removed one complication, but it led to the question of advance. The imperial officers urged a retreat. Abul Fazl had been bred in a cloister; he was approaching his fiftieth year; he had never before been in active service, but he had the spirit of a soldier; he refused to retreat from an enemy’s country; he pushed manfully on for Ahmadnagar. His efforts were rewarded with success. The Queen-regent was assailed by other enemies, and yielded to her fate. She agreed that if Abul Fazl would punish her enemies, she would surrender the fortress of Ahmadnagar.

Tidings had now reached Akbar that his son Amurath was dead. He resolved to go in person to the Deccan. He left his eldest son, Selim, in charge of the government. He sent an advance force under his other son, Danyal, associated with the Khan Khanan. The advance force reached Burhanpur. There the disloyalty of Bahadur Khan was manifest; he refused to pay respects to Danyal. Akbar was encamped at Ujain when the news reached him. He ordered Abul Fazl to join him; he ordered Danyal to go on to Ahmadnagar; he then prepared for the subjugation of Bahadur Khan.

The story of the operations may be told in a few words. Danyal advanced to Ahmadnagar. Chand Bibi was slaughtered by her own soldiers. Ahmadnagar was occupied by the Moguls. Meanwhile Bahadur Khan abandoned Burhanpur and took refuge in the strong fortress of Asirghur. Akbar was joined by Abul Fazl and laid siege to Asirghur. The siege lasted six months. At last Bahadur Khan surrendered; his life was spared; henceforth he fades away from history.

So far Akbar had prospered; he had conquered the great highway into the Deccan–Malwa, Khandesh, Berar, and Ahmadnagar. He raised Abul Fazl to the command of four thousand. He resolved on conquering the Deccan. He was about to strike when his arm was arrested. His eldest son Selim had broken out in revolt. He had gone to Allahabad and assumed the title of padishah.

Akbar returned alone to Agra; he was falling on evil days. He effected a reconciliation with Selim; he saw that Selim was still rebellious at heart; that his best officers were inclining toward his undutiful son. In his perplexity he sent to the Deccan for Abul Fazl. The trusted servant hastened to join his imperial master. But Selim had always hated Abul Fazl. He instigated a Rajput chief of Bundelkund to waylay Abul Fazl. This chief was Bir Singh of Urchah. Bir Singh fell upon Abul Fazl near Nawar, killed him, and sent his head to Selim. Bir Singh fled from the wrath of the Padishah; he led the life of an outlaw in the jungle until he heard of the death of Akbar.

Akbar was deeply wounded by the murder of Abul Fazl. He thereby lost his chief support, his best trusted friend. Henceforth he seemed to yield to circumstances rather than to struggle against the world. Other misfortunes befell him: his mother died; his youngest son, Danyal, killed himself with drink in the Deccan; his own life was beginning to draw to a close.

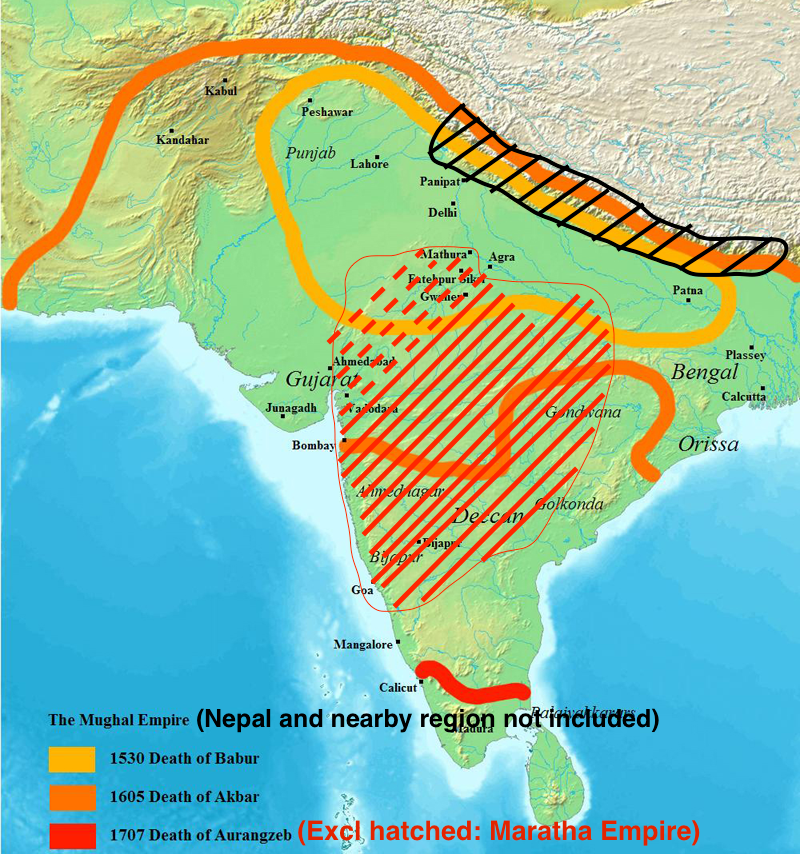

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The last events in the reign of Akbar are obscure. Outwardly he became reconciled to Selim. Outwardly he abandoned scepticism and heresy; he professed himself a Muslem. At heart he was anxious that Selim should be set aside; that Khuzru, the eldest son of Selim, should succeed him to the throne. It is impossible to unravel the intrigues that filled the court at Agra. At last Akbar was smitten with mortal disease. For some days Selim was refused admittance to his father’s chamber. In the end there was a compromise. Selim swore to maintain the Muslem religion. He also swore to pardon his son Khuzru and all who had supported Khuzru. He was then brought into the presence of Akbar. The old Padishah was past all speech. He made a sign with his hand that Selim should take the imperial diadem and gird on the imperial sword. Selim obeyed. He prostrated himself upon the ground before the couch of his dying father; he touched the ground with his head. He then left the chamber. A few hours had passed away and Akbar was dead. He died in October, 1605, aged sixty-three.

The burial of Akbar was performed after a simple fashion. His grave was prepared in a garden at Secundra, about four miles from Agra. The body was placed upon a bier. Selim and his three sons carried it out of the fortress. The young princes, assisted by the officers of the imperial household, carried it to Secundra. Seven days were spent in mourning over the grave. Provisions and sweetmeats were distributed among the poor every morning and evening throughout the mourning. Twenty readers were appointed to recite the Koran every night without ceasing. Finally, the foundations were laid of that splendid mausoleum which is known far and wide as the tomb of Akbar.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Akbar Establishes Moghul Empire in India by James Talboys Wheeler from his book The History of India: Mogul Empire published in 1881. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.