No wonder that the magistrate who presided at the martyrdom of St. Romanus calls them in Prudentius “a rebel people.”

Today we continue Christianity Appears

with a selection from by John Henry Newman. The selections are presented in a series of installments for 5 minute daily reading.

Previously in Christianity Appears.

What has been said will suggest another point of view in which the oriental rites were obnoxious to the government — namely, as being vagrant and proselytizing religions. If it tolerated foreign superstitions, this would be on the ground that districts or countries within its jurisdiction held them; to proselytize to a rite hitherto unknown, to form a new party, and to propagate it through the empire — a religion not local, but catholic — was an offence against both order and reason. The State desired peace everywhere, and no change; “considering,” according to Lactantius, “that they were rightly and deservedly punished who execrated the public religion handed down to them by their ancestors.”

It is impossible, surely, to deny that, in assembling for religious purposes, the Christians were breaking a solemn law, a vital principle of the Roman constitution; and this is the light in which their conduct was regarded by the historians and philosophers of the empire. This was a very strong act on the part of the disciples of the great apostle, who had enjoined obedience to the powers that be. Time after time they resisted the authority of the magistrate; and this is a phenomenon inexplicable on the theory of private judgment or of the voluntary principle. The justification of such disobedience lies simply in the necessity of obeying the higher authority of some divine law; but if Christianity were in its essence only private and personal, as so many now think, there was no necessity of their meeting together at all. If, on the other hand, in assembling for worship and holy communion, they were fulfilling an indispensable observance, Christianity has imposed a social law on the world, and formally enters the field of politics. Gibbon says that, in consequence of Pliny’s edict, “the prudence of the Christians suspended their agapa; but it was impossible for them to omit the exercise of public worship.” We can draw no other conclusion.

At the end of three hundred years a more remarkable violation of law seems to have been admitted by the Christian body. It shall be given in the words of Dr. Burton; he has been speaking of Maximin’s edict, which provided for the restitution of any of their lands or buildings which had been alienated from them.

It is plain,” he says, “from the terms of this edict, that the Christians had for some time been in possession of property. It speaks of houses and lands which did not belong to individuals, but to the whole body. Their possession of such property could hardly have escaped the notice of the government; but it seems to have been held in direct violation of a law of Diocletian, which prohibited corporate bodies or associations which were not legally recognized, from acquiring property. The Christians were certainly not a body recognized by law at the beginning of the reign of Diocletian, and it might almost be thought that this enactment was specially directed against them. But, like other laws which are founded upon tyranny, and are at variance with the first principles of justice, it is probable that this law about corporate property was evaded. We must suppose that the Christians had purchased lands and houses before the law was passed; and their disregard of the prohibition may be taken as another proof that their religion had now taken so firm a footing that the executors of the laws were obliged to connive at their being broken by so numerous a body.”

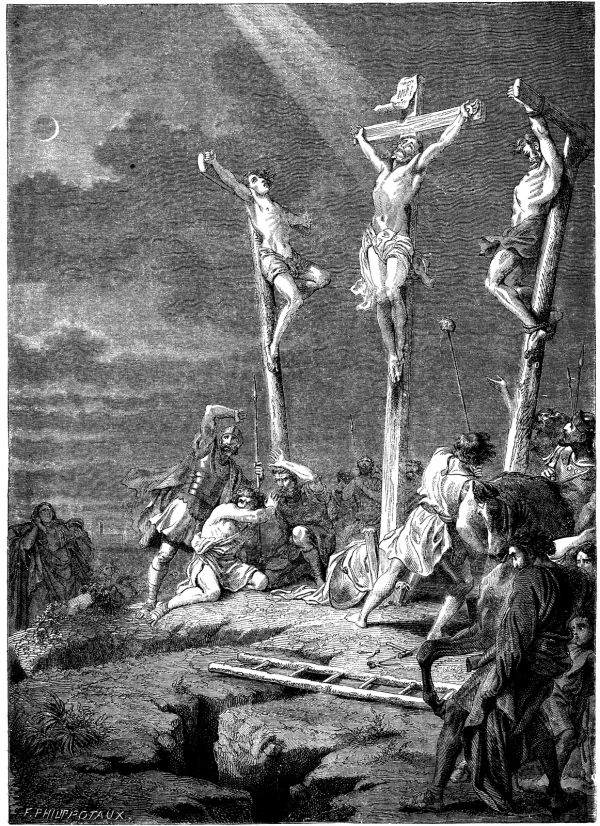

No wonder that the magistrate who presided at the martyrdom of St. Romanus calls them in Prudentius “a rebel people”; that Galerius speaks of them as “a nefarious conspiracy”; the heathen in Minucius, as “men of a desperate faction”; that others make them guilty of sacrilege and treason, and call them by those other titles which, more closely resembling the language of Tacitus, have been noticed above. Hence the violent accusations against them as the destructors of the empire, the authors of physical evils, and the cause of the anger of the gods.

Men cry out,” says Tertullian, “that the State is beset, that the Christians are in their fields, in their forts, in their islands. They mourn as for a loss that every sex, condition, and now even rank is going over to this sect. And yet they do not by this very means advance their minds to the idea of some good therein hidden; they allow not themselves to conjecture more rightly, they choose not to examine more closely. The generality run upon a hatred of this name, with eyes so closed that in bearing favorable testimony to anyone they mingle with it the reproach of the name. ‘A good man Caius Seius, only he is a Christian.’ So another, ‘I marvel that that wise man Lucius Titius hath suddenly become a Christian.’ No one reflecteth whether Caius be not therefore good and Lucius wise because a Christian, or therefore a Christian because wise and good. They praise that which they know, they revile that which they know not. Virtue is not in such account as hatred of the Christians. Now, then, if the hatred be of the name, what guilt is there in names? What charge against words? Unless it be that any word which is a name have either a barbarous or ill-omened, or a scurrilous or an immodest sound. If the Tiber cometh up to the walls, if the Nile cometh not up to the fields, if the heaven hath stood still, if the earth hath been moved, if there be any famine, if any pestilence, ‘The Christians to the lions’ is forthwith the word.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

J. Ernest Renan begins here. Isaac M. Wise begins here. John Henry Newman begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.