It is observable that, in the growing countenance which was extended to these rites in the third century, Christianity came in for a share.

Today we continue Christianity Appears

with a selection by John Henry Newman. The selections are presented in a series of installments for 5 minute daily reading.

Previously in Christianity Appears.

Before the mission of the apostles a movement, of which there had been earlier parallels, had begun in Egypt, Syria, and the neighboring countries, tending to the propagation of new and peculiar forms of worship throughout the empire. Prophecies were afloat that some new order of things was coming in from the East, which increased the existing unsettlement of the popular mind; pretenders made attempts to satisfy its wants, and old traditions of the truth, embodied for ages in local or in national religions, gave to these attempts a doctrinal and ritual shape, which became an additional point of resemblance to that truth which was soon visibly to appear.

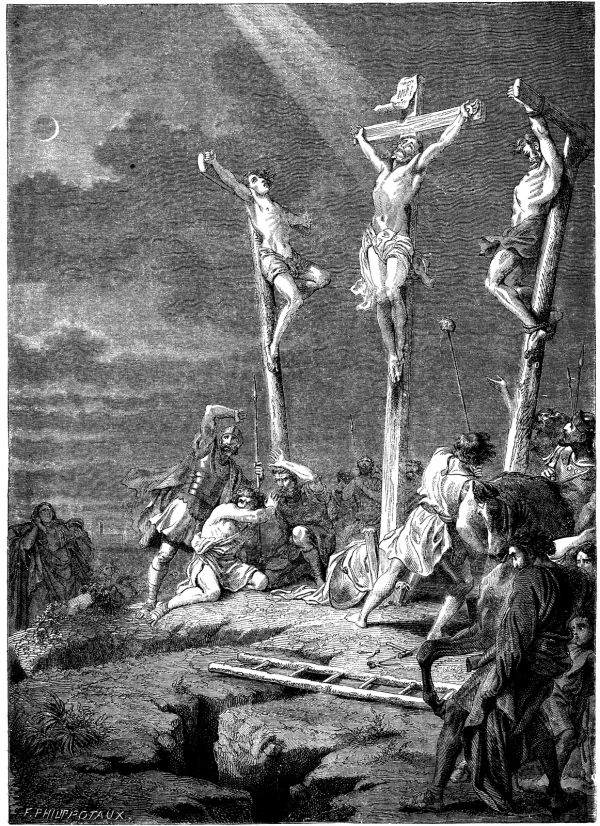

The distinctive character of the rites in question lay in their appealing to the gloomy rather than to the cheerful and hopeful feelings, and in their influencing the mind through fear. The notions of guilt and expiation, of evil and good to come, and of dealings with the invisible world, were in some shape or other preeminent in them, and formed a striking contrast to the classical polytheism, which was gay and graceful, as was natural in a civilized age. The new rites, on the other hand, were secret; their doctrine was mysterious; their profession was a discipline, beginning in a formal initiation, manifested in an association, and exercised in privation and pain. They were from the nature of the case proselytizing societies, for they were rising into power; nor were they local, but vagrant, restless, intrusive, and encroaching. Their pretensions to supernatural knowledge brought them into easy connection with magic and astrology, which are as attractive to the wealthy and luxurious as the more vulgar superstitions to the populace.

The Christian, being at first accounted a kind of Jew, was even on that score included in whatever odium, and whatever bad associations, attended on the Jewish name. But in a little time his independence of the rejected people was clearly understood, as even the persecutions show; and he stood upon his own ground. Still his character did not change in the eyes of the world; for favor or for reproach, he was still associated with the votaries of secret and magical rites. The emperor Hadrian, noted as he is for his inquisitive temper, and a partaker in so many mysteries, still believed that the Christians of Egypt allowed themselves in the worship of Serapis. They are brought into connection with the magic of Egypt in the history of what is commonly called the Thundering legion, so far as this, that the rain which relieved the Emperor’s army in the field, and which the Church ascribed to the prayers of the Christian soldiers, is by Dio Cassius attributed to an Egyptian magician, who obtained it by invoking Mercury and other spirits. This war had been the occasion of one of the first recognitions which the State had conceded to the oriental rites, though statesmen and emperors, as private men, had long taken part in them. The emperor Marcus had been urged by his fears of the Marcomanni to resort to these foreign introductions, and is said to have employed Magi and Chaldeans in averting an unsuccessful issue of the war.

It is observable that, in the growing countenance which was extended to these rites in the third century, Christianity came in for a share. The chapel of Alexander Severus contained statues of Abraham, Orpheus, Apollonius, Pythagoras, and our Lord. Here indeed, as in the case of Zenobia’s Judaism, an eclectic philosophy aided the comprehension of religions. But, immediately before Alexander, Heliogabalus, who was no philosopher, while he formally seated his Syrian idol in the Palatine, while he observed the mysteries of Cybele and Adonis, and celebrated his magic rites with human victims, intended also, according to Lampridius, to unite with his horrible superstition “the Jewish and Samaritan religions and the Christian rite, that so the priesthood of Heliogabalus might comprise the mystery of every worship.” Hence, more or less, the stories which occur in ecclesiastical history of the conversion or good-will of the emperors to the Christian faith, of Hadrian, Mammea, and others, besides Heliogabalus and Alexander. Such stories might often mean little more than that they favored it among other forms of oriental superstition.

What has been said is sufficient to bring before the mind an historical fact, which indeed does not need evidence. Upon the established religions of Europe the East had renewed her encroachments, and was pouring forth a family of rites which in various ways attracted the attention of the luxurious, the political, the ignorant, the restless, and the remorseful. Armenian, Chaldeen, Egyptian, Jew, Syrian, Phrygian, as the case might be, was the designation of the new hierophant; and magic, superstition, barbarism, jugglery, were the names given to his rite by the world. In this company appeared Christianity. When then three well-informed writers call Christianity a superstition and a magical superstition, they were not using words at random, or the language of abuse, but they were describing it in distinct and recognized terms as cognate to those gloomy, secret, odious, disreputable religions which were making so much disturbance up and down the empire.

The Gnostic family suitably traces its origin to a mixed race, which had commenced its national history by associating orientalism with revelation. After the captivity of the ten tribes Samaria was colonized by “men from Babylon and Cushan, and from Ava, and from Hamath, and from Sepharvaim,” who were instructed at their own instance in “the manner of the God of the land,” by one of the priests of the Church of Jeroboam. The consequence was that “they feared the Lord and served their own gods.” Of this country was Simon, the reputed patriarch of the Gnostics; and he is introduced in the Acts of the Apostles as professing those magical powers which were so principal a characteristic of the oriental mysteries. His heresy, though broken into a multitude of sects, was poured over the world with a catholicity not inferior in its day to that of Christianity. St. Peter, who fell in with him originally in Samaria, seems to have encountered him again at Rome. At Rome St. Polycarp met Marcion of Pontus, whose followers spread through Italy, Egypt, Syria, Arabia, and Persia.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

J. Ernest Renan begins here. Isaac M. Wise begins here. John Henry Newman begins here. More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.