They associated Christianity with the oriental superstitions, whether propagated by individuals or embodied in a rite, which were in that day traversing the empire.

Today we continue Christianity Appears

with a selection from by John Henry Newman. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selections are presented in a series of installments for 5 minute daily reading.

Newman converted to Catholicism from the Church of England, ending up as a cardinal. He was beatified in 2010.

Previously in Christianity Appears.

The prima-facie view of early Christianity, in the eyes of witnesses external to it, is presented to us in the brief but vivid descriptions given by Tacitus, Suetonius, and Pliny, the only heathen writers who distinctly mention it for the first hundred and fifty years.

Tacitus is led to speak of the religion, on occasion of the conflagration of Rome, which was popularly imputed to Nero.

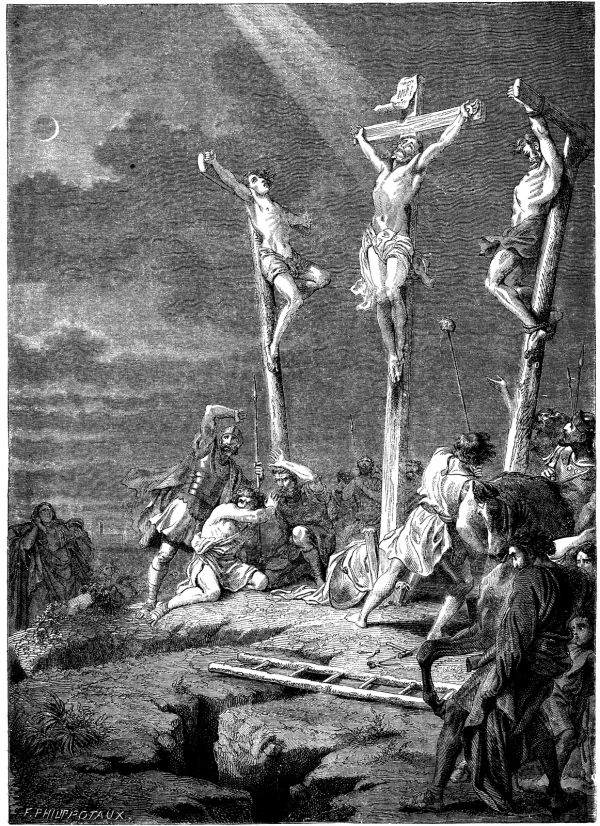

“To put an end to the report,” he says, “he laid the guilt on others, and visited them with the most exquisite punishment, those, namely, who, held in abhorrence for their crimes (per flagitia invisos), were popularly called Christians. The author of that profession (nominis) was Christ, who, in the reign of Tiberius, was capitally punished by the procurator, Pontius Pilate. The deadly superstition (exitiabilis superstitio), though checked for a while, broke out afresh; and that, not only throughout Judea, the original seat of the evil, but through the city also, whither all things atrocious or shocking (atrocia aut pudenda) flow together from every quarter and thrive. At first, certain were seized who avowed it; then, on their report, a vast multitude were convicted not so much of firing the city, as of hatred of mankind (odio humani generis).” After describing their tortures, he continues: “In consequence, though they were guilty, and deserved most signal punishment, they began to be pitied, as if destroyed not for any public object, but from the barbarity of one man.”

Suetonius relates the same transactions thus:

Capital punishments were inflicted on the Christians, a class of men of a new and magical superstition (superstitionis nova et malefica¦).” What gives additional character to this statement is its context, for it occurs as one out of various police or sanctuary or domestic regulations, which Nero made, such as “controlling private expenses, forbidding taverns to serve meat, repressing the contests of theatrical parties, and securing the integrity of wills.”

When Pliny was governor of Pontus, he wrote his celebrated letter to the emperor Trajan, to ask advice how he was to deal with the Christians, whom he found there in great numbers. One of his points of hesitation was whether the very profession of Christianity was not by itself sufficient to justify punishment; “whether the name itself should be visited, though clear of flagitious acts (flagitia), or only when connected with them.” He says he had ordered for execution such as persevered in their profession after repeated warnings, “as not doubting, whatever it was they professed, that at any rate contumacy and inflexible obstinacy ought to be punished.” He required them to invoke the gods, to sacrifice wine and frankincense to the images of the Emperor, and to blaspheme Christ; “to which,” he adds, “it is said no real Christian can be compelled.” Renegades informed him that “the sum total of their offence or fault was meeting before light on an appointed day, and saying with one another a form of words (carmen) to Christ, as if to a god, and binding themselves by oath (not to the commission of any wickedness, but) against the commission of theft, robbery, adultery, breach of trust, denial of deposits; that, after this they were accustomed to separate, and then to meet again for a meal, but eaten all together and harmless; however, that they had even left this off after his edicts enforcing the imperial prohibition of associations.” He proceeded to put two women to the torture, but “discovered nothing beyond a bad and excessive superstition” (superstitionem pravam et immodicam), “the contagion” of which, he continues, “had spread through villages and country, till the temples were emptied of worshippers.”

In these testimonies, which will form a natural and convenient text for what is to follow, we have various characteristics brought before us of the religion to which they relate. It was a superstition, as all three writers agree; a bad and excessive superstition, according to Pliny; a magical superstition, according to Suetonius; a deadly superstition, according to Tacitus. Next, it was embodied in a society, and, moreover, a secret and unlawful society and it was a proselytizing society; and its very name was connected with “flagitious,” “atrocious,” and “shocking” acts.

Now these few points, which are not all which might be set down, contain in themselves a distinct and significant description of Christianity; but they have far greater meaning when illustrated by the history of the times, the testimony of later writers, and the acts of the Roman government toward its professors. It is impossible to mistake the judgment passed on the religion by these three writers, and still more clearly by other writers and imperial functionaries. They evidently associated Christianity with the oriental superstitions, whether propagated by individuals or embodied in a rite, which were in that day traversing the empire, and which in the event acted so remarkable a part in breaking up the national forms of worship, and so in preparing the way for Christianity. This, then, is the broad view which the educated heathen took of Christianity; and, if it had been very unlike those rites and curious arts in external appearance, they would not have confused it with them.

Changes in society are by a providential appointment commonly preceded and facilitated by the setting in of a certain current in men’s thoughts and feelings in that direction toward which a change is to be made. And, as lighter substances whirl about before the tempest and presage it, so words and deeds, ominous but not effective of the coming revolution, are circulated beforehand through the multitude or pass across the field of events. This was specially the case with Christianity, as became its high dignity; it came heralded and attended by a crowd of shadows, shadows of itself, impotent and monstrous as shadows are, but not at first sight distinguishable from it by common spectators.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

J. Ernest Renan begins here. Isaac M. Wise begi0ns here. John Henry Newman begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.