What had men of the world to do with abstract proofs or first principles? A statesman measures parties and sects and writers by their bearing upon him; and he has a practiced eye in this sort of judgment, and is not likely to be mistaken.

Today we continue Christianity Appears

with a selection by John Henry Newman. The selections are presented in a series of installments for 5 minute daily reading.

Previously in Christianity Appears.

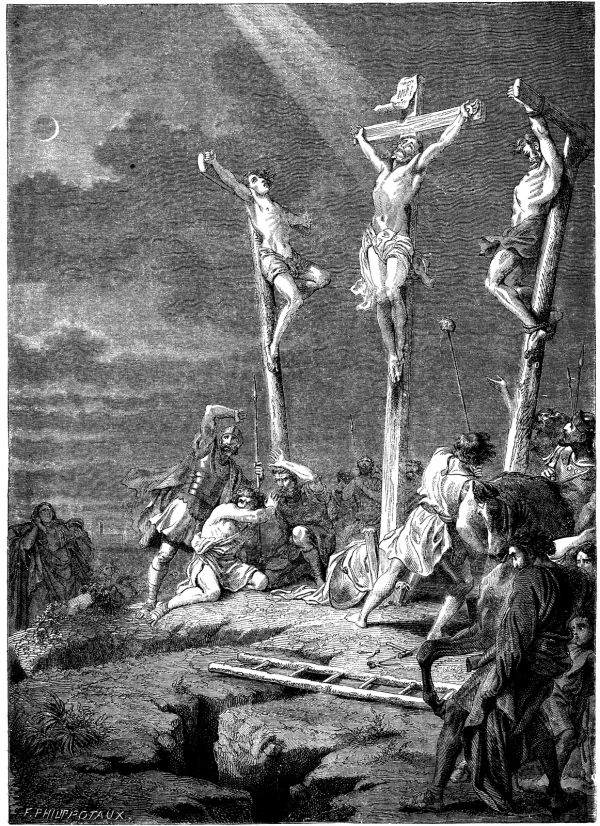

Hence the epithets of itinerant, mountebank, conjurer, cheat, sophist, and sorcerer, heaped upon the teachers of Christianity; sometimes to account for the report or apparent truth of their miracles, sometimes to explain their success. Our Lord was said to have learned his miraculous power in Egypt; “wizard, mediciner, cheat, rogue, conjurer,” were the epithets applied to him by the opponents of Eusebius; they “worship that crucified sophist,” says Lucian; “Paul, who surpasses all the conjurers and impostors who ever lived,” is Julian’s account of the apostle. “You have sent through the whole world,” says St. Justin to Trypho, “to preach that a certain atheistic and lawless sect has sprung from one Jesus, a Galilean cheat.” “We know,” says Lucian, speaking of Chaldæans and magicians, “the Syrian from Palestine, who is the sophist in these matters, how many lunatics, with eyes distorted and mouth in foam, he raises and sends away restored, ridding them from the evil at a great price.” “If any conjurer came to them, a man of skill and knowing how to manage matters,” says the same writer, “he made money in no time, with a broad grin at the simple fellows.” The officer who had custody of St. Perpetua feared her escape from prison “by magical incantations.” When St. Tiburtius had walked barefoot on hot coals, his judge cried out that Christ had taught him magic. St. Anastasia was thrown into prison as a mediciner; the populace called out against St. Agnes, “Away with the witch,” Tolle magam, tolle maleficam. When St. Bonosus and St. Maximilian bore the burning pitch without shrinking, Jews and Gentiles cried out, “Isti magi et malefici.” “What new delusion,” says the heathen magistrate concerning St. Romanus, “has brought in these sophists to deny the worship of the gods? How doth this chief sorcerer mock us, skilled by his Thessalian charm (carmine) to laugh at punishment!”

It explains the phenomenon, which has created so much surprise to certain moderns — that a grave, well-informed historian like Tacitus should apply to Christians what sounds like abuse. Yet what is the difficulty, supposing that Christians were considered mathematici and magi, and these were the secret intriguers against established government, the allies of desperate politicians, the enemies of the established religion, the disseminators of lying rumors, the perpetrators of poisonings and other crimes? “Read this,” says Paley, after quoting some of the most beautiful and subduing passages of St. Paul, “read this, and then think of exitiabilis superstitio“; and he goes on to express a wish “in contending with heathen authorities, to produce our books against theirs,” as if it were a matter of books.

Public men care very little for books; the finest sentiments, the most luminous philosophy, the deepest theology, inspiration itself, moves them but little; they look at facts, and care only for facts. The question was, What was the worth, what the tendency of the Christian body in the State? What Christians said, what they thought, was little to the purpose. They might exhort to peaceableness and passive obedience as strongly as words could speak; but what did they do, what was their political position? This is what statesmen thought of then, as they do now. What had men of the world to do with abstract proofs or first principles? A statesman measures parties and sects and writers by their bearing upon him; and he has a practiced eye in this sort of judgment, and is not likely to be mistaken. “‘What is Truth?’ said jesting Pilate.” Apologies, however eloquent or true, availed nothing with the Roman magistrate against the sure instinct which taught him to dread Christianity. It was a dangerous enemy to any power not built upon itself; he felt it, and the event justified his apprehension.

We must not forget the well-known character of the Roman State in its dealings with its subjects. It had had from the first an extreme jealousy of secret societies; it was prepared to grant a large toleration and a broad comprehension, but, as is the case with modern governments, it wished to have jurisdiction and the ultimate authority in every movement of the body politic and social, and its civil institutions were based, or essentially depended, on its religion. Accordingly, every innovation upon the established paganism, except it was allowed by the law, was rigidly repressed. Hence the professors of low superstitions, of mysteries, of magic, of astrology, were the outlaws of society, and were in a condition analogous, if the comparison may be allowed, to smugglers or poachers among ourselves, or perhaps to burglars and highwaymen; for the Romans had ever burnt the sorcerer and banished his consulters for life. It was an ancient custom. And at mysteries they looked with especial suspicion, because, since the established religion did not include them in its provisions, they really did supply what may be called a demand of the age.

We know what opposition had been made in Rome even to the philosophy of Greece; much greater would be the aversion of constitutional statesmen and lawyers to the ritual of barbarians. Religion was the Roman point of honor. “Spaniards might rival them in numbers,” says Cicero, “Gauls in bodily strength, Carthaginians in address, Greeks in the arts, Italians and Latins in native talent, but the Romans surpassed all nations in piety and devotion.” It was one of their laws, “Let no one have gods by himself, nor worship in private new gods nor adventitious, unless added on public authority.” Macenas in Dio advises Augustus to honor the gods according to the national custom, because the contempt of the country’s deities leads to civil insubordination, reception of foreign laws, conspiracies, and secret meetings. “Suffer no one,” he adds, “to deny the gods or to practice sorcery.” The civilian Julius Paulus lays it down as one of the leading principles of Roman law, that those who introduce new or untried religions should be degraded, and if in the lower orders put to death. In like manner, it is enacted in one of Constantine’s laws that the haruspices should not exercise their art in private; and there is a law of Valentinian’s against nocturnal sacrifices or magic. It is more immediately to our purpose that Trajan had been so earnest in his resistance to secret societies, that, when a fire had laid waste Nicomedia, and Pliny proposed to him to incorporate a body of a hundred and fifty firemen in consequence, he was afraid of the precedent and forbade it.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

J. Ernest Renan begins here. Isaac M. Wise begins here. John Henry Newman begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.