By this time the grenadiers and light infantry had lost three-fourths of their men; some companies had only eight or nine men left, one or two had even fewer.

Continuing The Battle Of Bunker Hill,

with a selection from Memoirs of the Life of King George III by John Heneage Jesse published in 1867. This selection are presented in 0.5 installments for 5 minute daily reading. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Battle Of Bunker Hill.

Time: 1775

Place: Outside of Boston

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

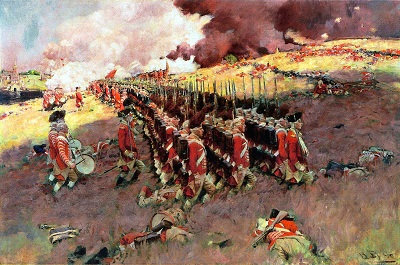

It was after 3 P.M. when General Howe’s detachment, consisting of about two thousand men, landed at Charlestown and formed for the attack. Prescott’s instructions to his men, as the British approached, were sufficiently brief. “The red-coats,” he said, “will never reach the redoubt if you will but withhold your fire till I give the order, and be careful not to shoot over their heads.” In the mean time, ascending the hill under the protection of a heavy cannonade, the British infantry had advanced unmolested to within a few yards of the enemy’s works, when Prescott gave the word “Fire!” So promptly and effectually were his orders obeyed that nearly the whole front rank of the British fell. Volley after volley was now opened upon them from behind the entrenchments, till at length even the bravest began to waver and fall back; some of them, in spite of the threats and passionate entreaties of their officers, even retreating to the boats.

Minutes, many minutes apparently, elapsed before the British troops were rallied and returned to the attack, exposed to the burning rays of the sun, encumbered with heavy knapsacks containing provisions for three days, compelled to toil up very disadvantageous ground with grass reaching to their knees, clambering over rails and hedges, and led against men who were fighting from behind entrenchments and constantly receiving reinforcements by hundreds — few soldiers, perhaps, but British infantry would have been prevailed upon to renew the conflict. Again, however, they advanced to the charge; again, when within five or six rods of the redoubt, the same tremendous discharge of musketry was opened upon them; and again, in spite of many heroic examples of gallantry set them by their officers, they retreated in the same disorder as before.

By this time the grenadiers and light infantry had lost three-fourths of their men; some companies had only eight or nine men left, one or two had even fewer. When the Americans looked forth from their entrenchments the ground was literally covered with the wounded and dead. According to an American who was present, “the dead lay as thick as sheep in a fold.” For a few seconds General Howe was left almost alone. Nearly every officer of his staff had been either killed or wounded. The Americans, who have done honorable justice to his gallantry, remarked that, conspicuous as he stood in his general officer’s uniform, it was a marvel that he escaped unhurt. He retired, but it was with the stern resolve of a hero to rally his men–to return and vanquish.

The third and last attack made by General Howe upon the enemy’s entrenchments appears to have taken place after a considerably longer interval than the previous one. This interval was employed by Prescott in addressing words of confidence and exhortation to his followers, to which their cheers returned an enthusiastic response. “If we drive them back once more,” he said, “they cannot rally again.” General Howe, in the mean time, by disencumbering his men of their knapsacks, and by bringing the British artillery to play so as to rake the interior of the American breastwork, had greatly enhanced his chances of success. Once more, at the word of command, in steady unbroken line, the British infantry mounted to the deadly struggle; once more the cheerful voice of Prescott exhorted his men to reserve their fire till their enemies were close upon them; once more the same deadly fire was poured down upon the advancing royalists. Again on their part there was a struggle, a pause, an indication of wavering; but on this occasion it was only momentary. Onward and headlong against breastwork and against vastly superior numbers dashed the British infantry, with a heroic devotion never surpassed in the annals of chivalry. Almost in a moment of time, in spite of a second volley as destructive as the first, the ditch was leaped and the parapet mounted.

In that final charge fell many of the bravest of the brave. Of the Fifty-second regiment alone, three captains, the moment they stood on the parapet, were shot down. Still the English infantry continued to pour forward, flinging themselves among the American militiamen, who met them with a gallantry equal to their own. The powder of the latter having by this time become nearly exhausted, they endeavored to force back their assailants with the butt-ends of their muskets. But the British bayonets carried all before them. Then it was, when further resistance was evidently fruitless, and not till then, that the heroic Prescott gave the order to retire. From the nature of the ground it was necessarily more a flight than a retreat. Many of the Americans, leaping over the walls of the parapet, attempted to fight their way through the British troops; while the majority endeavored to escape by the narrow entrance to the redoubt. In consequence of the fugitives being thus huddled together, the slaughter became terrific.

“Nothing,” writes a young British officer, who was engaged in the melee, “could be more shocking than the carnage that followed the storming of this work. We tumbled over the dead to get at the living, who were crowding out of the gap of the redoubt, in order to form under the defenses which they had prepared to cover their retreat.” Prescott was one of the last to quit the scene of slaughter. Although more than one British bayonet had pierced his clothes, he escaped without a wound.

That night the British entrenched themselves on the heights, lying down in front of the recent scene of contest. The loss in killed and wounded was ten hundred fifty-four. According to the American account their loss was one hundred forty-five killed and three hundred four wounded; of their six pieces of artillery, they only succeeded in carrying off one.

Such was the result of the famous Battle of Bunker Hill, a contest from which Great Britain derived little advantage beyond the credit of having achieved a brilliant passage of arms, but which, on the other hand, produced the significant effect of manifesting, not only to the Americans themselves, but to Europe, that the colonists could fight with a steadiness and courage which ere long might render them capable of coping with the disciplined troops of the mother-country.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

John Burgoyne begins here. John Heneage Jesse begins here. James Grahame begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.