The Battle of Quebec, in 1759, which gave Great Britain the colony of Canada, was not so destructive to British officers as this affair of a slight entrenchment, the work only of a few hours.

Today’s installment concludes The Battle Of Bunker Hill,

the name of our combined selection from John Burgoyne, John Heneage Jesse, and James Grahame. The concluding installment,by James Grahame from History of the United States of North America, was published in 1836.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of four thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Battle Of Bunker Hill.

Time: 1775

Place: Outside of Boston

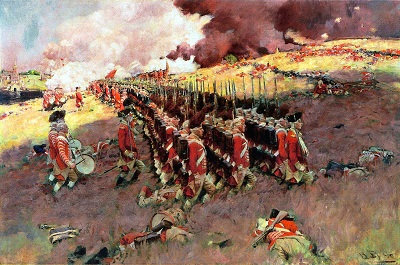

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

While these operations were going on at the breastwork and redoubt, the British light infantry were attempting to force the left point of the former, that they might take the American line in flank. Though they exhibited the most undaunted courage, they met with an opposition which called for its greatest exertions. The provincials reserved their fire till their adversaries were near, and then discharged it upon the light infantry in such an incessant stream, and with so true an aim, as that it quickly thinned their ranks. The engagement was kept up on both sides with great resolution. The persevering exertions of the King’s troops could not compel the Americans to retreat till they observed that their main body had left the hill. This, when begun, exposed them to new dangers; for it could not be effected but by marching over Charlestown Neck, every part of which was raked by the shot of the Glasgow (man-of-war) and of two floating batteries. The incessant fire kept up across the Neck prevented any considerable reinforcement from joining their countrymen who were engaged; but the few who fell on their retreat over the same ground proved that the apprehensions of those provincial officers, who declined passing over to succor their companies, were without any solid foundation.

The number of Americans engaged amounted only to fifteen hundred. It was apprehended that the conquerors would push the advantage they had gained, and march immediately to American headquarters at Cambridge; but they advanced no farther than Bunker Hill. There they threw up works for their own security. The provincials did the same, on Prospect Hill, in front of them. Both were guarding against an attack; and both were in a bad condition to receive one. The loss of the peninsula depressed the spirits of the Americans; and the great loss of men produced the same effect on the British. There have been few battles in modern wars in which, all circumstances considered, there was a greater destruction of men than in this short engagement.

The loss of the British, as acknowledged by General Gage, amounted to one thousand fifty-four. Nineteen commissioned officers were killed and seventy more were wounded. The Battle of Quebec, in 1759, which gave Great Britain the colony of Canada, was not so destructive to British officers as this affair of a slight entrenchment, the work only of a few hours. That the officers suffered so much must be imputed to their being aimed at. None of the provincials in this engagement were riflemen, but they were all good marksmen. The whole of their previous military knowledge had been derived from hunting and the ordinary amusements of sportsmen. The dexterity which by long habit they had acquired in hitting beast, birds, and marks, was fatally applied to the destruction of British officers. From their fall, much confusion was expected. They were therefore particularly singled out. Most of those who were near the person of General Howe were either killed or wounded; but the General, though he greatly exposed himself, was unhurt. The light infantry and grenadiers lost three-fourths of their men. Of one company not more than five, and of another not more than fourteen, escaped.

The unexpected resistance of the Americans was such as wiped away the reproach of cowardice, which had been cast upon them by their enemies in Britain. The spirited conduct of the British officers merited and obtained great applause; but the provincials were justly entitled to a large share of the glory for having made the utmost exertions of their adversaries necessary to dislodge them from lines which were the work of only a single night.

The Americans lost five pieces of cannon. Their killed amounted to one hundred thirty-nine; their wounded and missing, to three hundred fourteen. Thirty of the former fell into the hands of the conquerors. They particularly regretted the death of General Warren. To the purest patriotism and most undaunted bravery he added the virtues of domestic life, the eloquence of an accomplished orator, and the wisdom of an able statesman. Only a regard for the liberty of his country induced him to oppose the measures of Government. He aimed not at a separation from, but a coalition with, the mother-country.

The burning of Charlestown, though a place of great trade, did not discourage the provincials. It excited resentment and execration, but not any disposition to submit. Such was the high-strung state of the public mind, and so great the indifference of property when put in competition with liberty, that military conflagrations, though they distressed and impoverished, had no tendency to subdue, the colonists. Such means might suffice in the Old World, but were not effectual in the New, where the war was undertaken, not for a change of masters, but for securing essential rights.

The action at Breed’s Hill, or Bunker Hill, as it has since been commonly called, produced many and very important consequences. It taught the British so much respect for the Americans, entrenched behind works, that their subsequent operations were retarded with a caution that wasted away a whole campaign to very little purpose. It added to the confidence the Americans began to have in their own abilities. It inspired some of the leading members of Congress with such high ideas of what might be done by militia, or men engaged for a short term of enlistment, that it was long before they assented to the establishment of a permanent army.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our selections on The Battle Of Bunker Hill by three of the most important authorities of this topic:

- [a letter home] by John Burgoyne.

- Memoirs of the Life of King George III by John Heneage Jesse published in 1867.

- History of the United States of North America by James Grahame published in 1836.

This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The Battle Of Bunker Hill here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.