Thousands, both within and without Boston, were anxious spectators of the bloody scene.

Today we continue The Battle Of Bunker Hill,

with a selection from History of the United States of North America by James Grahame published in 1836. This selection is presented in 0.5 installments for 5 minute daily reading. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Battle Of Bunker Hill.

Time: 1775

Place: Outside of Boston

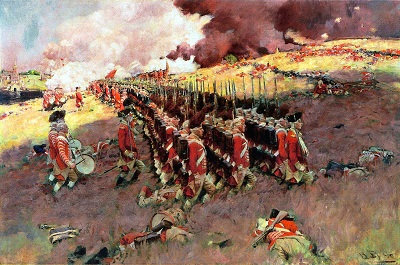

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

About the latter part of May, a great part of the reinforcements ordered from Great Britain arrived at Boston. Three British generals, Howe, Burgoyne, and Clinton, whose behavior in the preceding war had gained them great reputation, arrived about the same time. General Gage, thus reinforced, prepared for acting with more decision; but before he proceeded to extremities, he conceived it due to ancient forms to issue a proclamation, holding forth to the inhabitants the alternative of peace or war. He therefore offered pardon, in the King’s name, to all who should forthwith lay down their arms and return to their respective occupations and peaceable duties: excepting only from the benefit of that pardon “Samuel Adams and John Hancock, whose offences were said to be of too flagitious a nature to admit of any other consideration than that of condign punishment.” He also proclaimed that not only the persons above named and excepted, but also all their adherents, associates, and correspondents, should be deemed guilty of treason and rebellion, and treated accordingly. By this proclamation it was also declared “that as the courts of judicature were shut, martial law should take place till a due course of justice should be reestablished.”

It was supposed that this proclamation was a prelude to hostilities; and preparations were accordingly made by the Americans. A considerable height, by the name of Bunker Hill, just at the entrance of the peninsula of Charlestown, was so situated as to make the possession of it a matter of great consequence to either of the contending parties. Orders were therefore issued, by the provincial commanders, that a detachment of a thousand men should entrench upon this height. By some mistake, Breed’s Hill, high and large like the other, but situated nearer Boston, was marked out for the entrenchments, instead of Bunker Hill. The provincials proceeded to Breed’s Hill and worked with so much diligence that between midnight and the dawn of the morning they had thrown up a small redoubt about eight rods square. They kept such a profound silence that they were not heard by the British, on board their vessels, though very near. These having derived their first information of what was going on from the sight of the works, early completed, began an incessant firing upon them.

The provincials bore this with firmness, and, though they were only young soldiers, continued to labor till they had thrown up a small breastwork extending from the east side of the redoubt to the bottom of the hill. As this eminence overlooked Boston, General Gage thought it necessary to drive the provincials from it. About noon, therefore, he detached Major-General Howe and Brigadier-General Pigot, with the flower of his army, consisting of four battalions, ten companies of the grenadiers and ten of light infantry, with a proportion of field artillery, to effect this business. These troops landed at Moreton’s Point, and formed after landing, but remained in that position till they were reinforced by a second detachment of light infantry and grenadier companies, a battalion of land forces, and a battalion of marines, making in the whole nearly three thousand men. While the troops who first landed were waiting for this reinforcement, the provincials, for their further security, pulled up some adjoining post and rail fences, and set them down in two parallel lines at a small distance from each other, and filled the space between with hay, which, having been lately mowed, was found lying on the adjacent ground.

The King’s troops formed in two lines, and advanced slowly to give their artillery time to demolish the American works. While the British were advancing to the attack they received orders to burn Charlestown. These were not given because they were fired upon from the houses in that town, but from the military policy of depriving enemies of a cover in their approaches. In a short time this ancient town, consisting of about five hundred buildings, chiefly of wood, was in one great blaze. The lofty steeple of the meeting-house formed a pyramid of fire above the rest, and struck the astonished eyes of numerous beholders with a magnificent but awful spectacle. In Boston the heights of every kind were covered with citizens, and such of the King’s troops as were not on duty. The hills around the adjacent country, which afforded a safe and distinct view, were occupied by the inhabitants of the country.

Thousands, both within and without Boston, were anxious spectators of the bloody scene. Regard for the honor of the British army caused hearts to beat high in the breasts of many; while others, with keener sensibilities, sorrowed for the liberties of a great and growing country. The British moved on slowly, which gave the provincials a better opportunity for taking aim. The latter, in general, reserved their fire until their adversaries were within ten or twelve rods, and then began a furious discharge of small arms. The stream of the American fire was so incessant, and did so great execution, that the King’s troops retreated with precipitation and disorder. Their officers rallied them and pushed them forward with their swords; but they returned to the attack with great reluctance. The Americans again reserved their fire till their adversaries were near, and then put them a second time to flight. General Howe and the officers redoubled their exertions, and were again successful, though the soldiers displayed a great aversion to going on. By this time the powder of the Americans began so far to fail that they were not able to keep up the same brisk fire. The British then brought some cannon to bear, which raked the inside of the breastwork from end to end. The fire from the ships, batteries, and field artillery was redoubled; the soldiers in the rear were goaded on by their officers. The redoubt was attacked on three sides at once. Under these circumstances a retreat from it was ordered, but the provincials delayed so long, and made resistance with their discharged muskets as if they had been clubs, that the King’s troops, who had easily mounted the works, half filled the redoubt before it was given up to them.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

John Burgoyne begins here. John Heneage Jesse begins here. James Grahame begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.