In that epoch the persecutors of Christianity were not Romans; they were orthodox Jews.

Today we continue Christianity Appears

with a selection from Histoire des Origines du Christianisme by J. Ernest Renan published in 1881. The selections are presented in a series of installments for 5 minute daily reading.

Previously in Christianity Appears.

Time: 36

Place: Jerusalem

Stephen defended himself by expounding the Christian thesis, with a wealth of citations from the written Law, from the Psalms, from the Prophets, and wound up by reproaching the members of the Sanhedrim with the murder of Jesus. “Ye stiff-necked and uncircumcised in heart,” said he to them, “you will then ever resist the Holy Ghost as your fathers also have done. Which of the prophets have not your fathers prosecuted? They have slain those who announced the coming of the Just One, whom you have betrayed, and of whom you have been the murderers. This law that you have received from the mouth of angels you have not kept.” At these words a scream of rage interrupted him. Stephen, his excitement increasing more and more, fell into one of those transports of enthusiasm which were called the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. His eyes were fixed on high; he witnessed the glory of God, and Jesus by the side of his Father, and cried out, “Behold, I see the heavens opened, and the Son of Man sitting on the right hand of God.” The whole assembly stopped their ears and threw themselves upon him, gnashing their teeth. He was dragged outside the city and stoned. The witnesses, who, according to the law, had to cast the first stones, divested themselves of their garments and laid them at the feet of a young fanatic named Saul, or Paul, who was thinking with secret joy of the renown he was acquiring in participating in the death of a blasphemer.

In that epoch the persecutors of Christianity were not Romans; they were orthodox Jews. The Romans preserved in the midst of this fanaticism a principle of tolerance and of reason. If we can reproach the imperial authority with anything it is with being too lenient, and with not having cut short with a stroke the civil consequences of a sanguinary law which visited with death religious derelictions. But as yet the Roman domination was not so complete as it became later.

As Stephen’s death may have taken place at any time during the years 36, 37, 38, we cannot, therefore, affirm whether Caiaphas ought to be held responsible for it. Caiaphas was deposed by Lucius Vitellius, in the year 36, shortly after the time of Pilate; but the change was inconsiderable. He had for a successor his brother-in-law, Jonathan, son of Hanan. The latter, in turn, was succeeded by his brother Theophilus, son of Hanan, who continued the pontificate in the house of Hanan till the year 42. Hanan was still alive, and, possessed of the real power, maintained in his family the principles of pride, severity, hatred against innovators, which were, so to speak, hereditary.

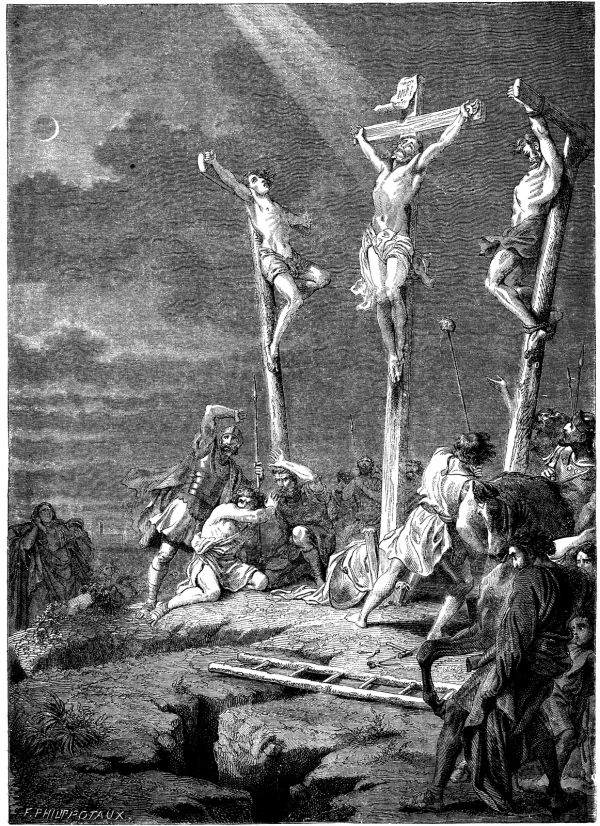

The death of Stephen produced a great impression. The proselytes solemnized his funeral with tears and groanings. The separation of the new sectaries from Judaism was not yet absolute. The proselytes and the Hellenists, less strict in regard to orthodoxy than the pure Jews, considered that they ought to render public homage to a man who respected their constitution, and whose peculiar beliefs did not put him without the pale of the law. Thus began the era of Christian martyrs.

The murder of Stephen was not an isolated event. Taking advantage of the weakness of the Roman functionaries, the Jews brought to bear upon the Church a real persecution. It seems that the vexations pressed chiefly on the Hellenists and the proselytes, whose free behavior exasperated the orthodox. The Church of Jerusalem, though already strongly organized, was compelled to disperse. The apostles, according to a principle which seems to have seized strong hold of their minds, did not quit the city. It was probably so, too, with the whole purely Jewish group, those who were denominated the “Hebrews.” But the great community with its common table, its diaconal services, its varied exercises, ceased from that time, and was never reformed upon its first model. It had endured for three or four years. It was for nascent Christianity an unequalled good fortune that its first attempts at association, essentially communistic, were so soon broken up. Essays of this kind engender such shocking abuses that communistic establishments are condemned to crumble away in a very short time or to ignore very soon the principle upon which they are founded.

Thanks to the persecution of the year 37, the cenobitic Church of Jerusalem was saved from the test of time. It was nipped in the bud before interior difficulties had undermined it. It remained like a splendid dream, the memory of which animated in their life of trial all those who had formed part of it, like an ideal to which Christianity incessantly aspires without ever succeeding in reaching its goal.

The leading part in the persecution we have just related belonged to that young Saul, whom we have above found abetting, as far as in him lay, the murder of Stephen. This hot-headed youth, furnished with a permission from the priests, entered houses suspected of harboring Christians, laid violent hold on men and women, and dragged them to prison or before the tribunals. Saul boasted that there was no one of his generation so zealous as himself for the traditions. True it is that often the gentleness and the resignation of his victims astonished him; he experienced a kind of remorse; he fancied he heard these pious women, whom, hoping for the Kingdom of God, he had cast into prison, saying during the night, in a sweet voice, “Why persecutest thou us?” The blood of Stephen, which had almost smothered him, sometimes troubled his vision. Many things that he had heard said of Jesus went to his heart. This superhuman being, in his ethereal life, whence he sometimes emerged, revealing himself in brief apparitions, haunted him like a spectre. But Saul shrunk with horror from such thoughts; he confirmed himself with a sort of frenzy in the faith of his traditions, and meditated new cruelties against those who attacked him. His name had become a terror to the faithful; they dreaded at his hands the most atrocious outrages and the most sanguinary treacheries.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

J. Ernest Renan begins here. Isaac M. Wise begins here. John Henry Newman begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.