This series is in four total installments for 5 minute reading. This installment: Burgoyne Sees “Greatest Scenes of War” at Bunker Hill.

This action, which took place about two months after the Battle of Lexington, though resulting in the physical defeat of the Americans, proved for them a moral victory. As at Lexington and Concord, the colonial soldiers showed that they were prepared to stand their ground in defense of the cause which called them to arms, and Bunker Hill became a watchword of the Revolution. This event also made it clear that the contest must be fought out. Thenceforth the two sides in the war were sharply defined.

The immediate occasion of this battle was the necessity, as seen by the British general, Gage, of driving the Americans from an eminence commanding Boston. This elevation was one of several hills on a peninsula just north of the town and running out into the harbor. It was the intention of the Americans to seize and fortify Bunker Hill, but for some unexplained reason they took Breed’s Hill, much nearer Boston, and there the battle was mainly fought. Breed’s Hill is now usually called Bunker Hill, and upon it stands the Bunker Hill monument.

The following accounts of the battle are all from British writers; one is that of the English officer General Burgoyne, who was afterward defeated at Saratoga; another is by the English historical author Jesse, whose best work covers the reign of George III. The third is from James Grahame, a native of Glasgow, Scotland, who died in 1842, of whose History of America a high authority says: “The thoroughly American spirit in which it is written prevented the success of the book in England.” The historian Prescott gave it high praise for accuracy and fairness.

The selections are from:

- [a letter home] by John Burgoyne.

- Memoirs of the Life of King George III by John Heneage Jesse published in 1867.

- History of the United States of North America by James Grahame published in 1836.

For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Summary of daily installments:

| John Burgoyne’s installments: | 0.5 |

| John Heneage Jesse’s installments: | 1.5 |

| James Grahame’s installments: | 2 |

| Total installments: | 4 |

We begin with John Burgoyne.

Time: 1775

Place: Outside of Boston

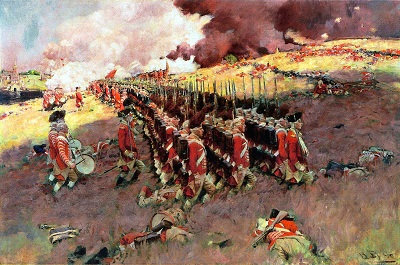

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

by John Burgoyne

Now ensued one of the greatest scenes of war that can be conceived. If we look to the height, Howe’s corps, ascending the hill in face of entrenchments, and in a very disadvantageous ground, was much engaged; to the left the enemy, pouring in fresh troops by thousands over the land; and in the arm of the sea our ships and floating batteries, cannonading them. Straight before us a large and noble town[*] in one great blaze; and the church-steeples, being timber, were great pyramids of fire above the rest. Behind us the church-steeples and heights of our own camp covered with spectators of the rest of our army which was engaged; the hills round the country also covered with spectators; the enemy all in anxious suspense; the roar of cannon, mortars, and musketry; the crash of churches, ships upon the stocks, and whole streets falling together, to fill the ear; the storm of the redoubts, with the objects above described, to fill the eye; and the reflection that perhaps a defeat was a final loss to the British empire of America, to fill the mind, made the whole a picture and a complication of horror and importance beyond anything that ever came to my lot to witness.

* Charlestown. A body of American riflemen, posted in the houses, galled the left line as it marched; therefore, by Howe’s orders, the town was set on fire.

by John Heneage Jesse

About 11 P.M. on June 16th a detachment of about a thousand men, who had previously joined solemnly together in prayer, ascended silently and stealthily a part of the heights known as Bunker Hill, situated within cannon range of Boston and commanding a view of every part of the town. This brigade was composed chiefly of husbandmen, who wore no uniform, and who were armed with fowling-pieces only, unequipped with bayonets. The person selected to command them on this daring service was one of the lords of the soil of Massachusetts, William Prescott, of Pepperell, the colonel of a Middlesex regiment of militia. “For myself,” he said to his men, “I am resolved never to be taken alive.” Preceded by two sergeants bearing dark-lanterns, and accompanied by his friends, Colonel Gridley and Judge Winthrop, the gallant Prescott, distinguished by his tall and commanding figure, though simply attired in his ordinary calico smock-frock, calmly and resolutely led the way to the heights. Those who followed him were not unworthy of their leader.

It was half-past eleven before the engineers commenced drawing the lines of the redoubt. As the first sod was being upturned, the clocks of Boston struck twelve. More than once during the night — which happened to be a beautifully calm and starry one–Colonel Prescott descended to the shore, where the sound of the British sentinels walking their rounds, and their exclamations of “All’s well!” as they relieved guard, continued to satisfy him that they entertained no suspicion of what was passing above their heads. Before daybreak the Americans had thrown up an entrenchment, which extended from the Mystic to a redoubt on their left. The astonishment of Gage, when on the following morning he found this important site in the hands of the enemy, may be readily conceived. Obviously not a moment was to be lost in attempting to dislodge them; and accordingly a detachment, under General Howe, was at once ordered on this critical service.

In the mean time a heavy cannonade, first of all from the Lively (sloop-of-war), and afterward from a battery of heavy guns from Copp’s hill, in Boston, was opened upon the Americans. Exposed, however, as they were to a storm of shot and shell, unaccustomed, as they also were, to face an enemy’s fire, they nevertheless pursued their operations with the calm courage of veteran soldiers.

Late in the day, indeed, when the scorching sun rose high in the cloudless heavens, when the continuous labors of so many hours threatened to prostrate them, and when they waited, but waited in vain, for provisions and refreshments, the hearts of a few began to fail them, and the word retreat was suffered to escape from their lips. There was among them, however, a master spirit, whose cheering words and chivalrous example never failed to restore confidence. On the spot–where now a lofty column, overlooking the fair landscape and calm waters, commemorates the events of that momentous day–was then seen, conspicuous above the rest, the form of Prescott of Pepperell, in his calico frock, as he paced the parapet to and fro, instilling resolution into his followers by the contempt which he manifested for danger, and amid the hottest of the British fire delivering his orders with the same serenity as if he had been on parade. “Who is that person?” inquired Governor Gage of a Massachusetts gentleman, as they stood reconnoitering the American works from the opposite side of the river Charles. “My brother-in-law, Colonel Prescott,” was the reply. “Will he fight?” asked Gage. “Ay,” said the other, “to the last drop of his blood.”

| Master List | Next—> |

John Burgoyne begins here. John Heneage Jesse begins here. James Grahame begins here.

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.