There can be no doubt that a third town, which seems to have been very populous, now existed.

Continuing The Foundation of Rome,

our selection from Roman History by Barthold Georg Niebuhr published in 1848. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in nine easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in The Foundation of Rome.

Time: 753 BC

Place: Rome

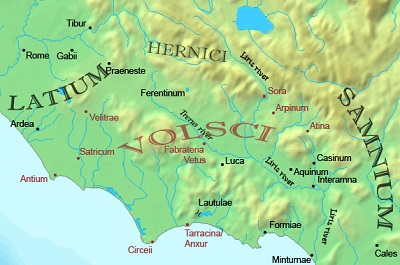

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The contest of the three brothers on each side is a symbolical indication that each of the two states was then divided into three tribes. Attempts have indeed been made to deny that the three men were brothers of the same birth, and thus to remove the improbability; but the legend went even further, representing the three brothers on each side as the sons of two sisters, and as born on the same day. This contains the suggestion of a perfect equality between Rome and Alba. The contest ended in the complete submission of Alba; it did not remain faithful, however, and in the ensuing struggle with the Etruscans, Mettius Fuffetius acted the part of a traitor toward Rome, but not being able to carry his design into effect, he afterward fell upon the fugitive Etruscans. Tullus ordered him to be torn to pieces and Alba to be razed to the ground, the noblest Alban families being transplanted to Rome. The death of Tullus is no less poetical. Like Numa he undertook to call down lightning from heaven, but he thereby destroyed himself and his house.

If we endeavor to discover the historical substance of these legends, we at once find ourselves in a period when Rome no longer stood alone, but had colonies with Roman settlers, possessing a third of the territory and exercising sovereign power over the original inhabitants. This was the case in a small number of towns, for the most part of ancient Siculian origin. It is an undoubted fact that Alba was destroyed, and that after this event the towns of the Prisci Latini formed an independent and compact confederacy; but whether Alba fell in the manner described, whether it was ever compelled to recognize the supremacy of Rome, and whether it was destroyed by the Romans and Latins conjointly, or by the Romans or Latins alone, are questions which no human ingenuity can solve. It is, however, most probable that the destruction of Alba was the work of the Latins, who rose against her supremacy; whether in this case the Romans received the Albans among themselves, and thus became their benefactors instead of destroyers, must ever remain a matter of uncertainty. That Alban families were transplanted to Rome cannot be doubted, any more than that the Prisci Latini from that time constituted a compact state; if we consider that Alba was situated in the midst of the Latin districts, that the Alban mount was their common sanctuary, and that the grove of Ferentina was the place of assembly for all the Latins, it must appear more probable that Rome did not destroy Alba, but that it perished in an insurrection of the Latin towns, and that the Romans strengthened themselves by receiving the Albans into their city.

Whether the Albans were the first that settled on the Cælian hill, or whether it was previously occupied, cannot be decided. The account which places the foundation of the town on the Cælius in the reign of Romulus suggests that a town existed there before the reception of the Albans; but what is the authenticity of this account? A third tradition represents it as an Etruscan settlement of Cæles Vibenna. This much is certain, that the destruction of Alba greatly contributed to increase the power of Rome. There can be no doubt that a third town, which seems to have been very populous, now existed on the Cælius and on a portion of the Esquiliæ: such a settlement close to other towns was made for the sake of mutual protection. Between the two more ancient towns there continued to be a marsh or swamp, and Rome was protected on the south by stagnant water; but between Rome and the third town there was a dry plain. Rome also had a considerable suburb toward the Aventine, protected by a wall and a ditch, as is implied in the story of Remus. He is a personification of the plebs, leaping across the ditch from the side of the Aventine, though we ought to be very cautious in regard to allegory.

The most ancient town on the Palatine was Rome; the Sabine town also must have had a name, and I have no doubt that, according to common analogy, it was Quirium, the name of its citizens being Quirites. This I look upon as certain. I have almost as little doubt that the town on the Cælian was called Lucerum, because when it was united with Rome, its citizens were called, Lucertes (Luceres). The ancients derive this name from Lucumo, king of the Tuscans, or from Lucerus, king of Ardea; the latter derivation probably meaning that the race was Tyrrheno-Latin, because Ardea was the capital of that race. Rome was thus enlarged by a third element, which, however, did not stand on a footing of equality with the two others, but was in a state of dependence similar to that of Ireland relatively to Great Britain down to the year 1782. But although the Luceres were obliged to recognize the supremacy of the two older tribes, they were considered as an integral part of the whole state, that is, as a third tribe with an administration of its own, but inferior rights. What throws light upon our way here is a passage of Festus, who is a great authority on matters of Roman antiquity, because he made his excerpts from Verrius Flaccus; it is only in a few points that, in my opinion, either of them was mistaken; all the rest of the mistakes in Festus may be accounted for by the imperfection of the abridgment, Festus not always understanding Verrius Flaccus. The statement of Festus to which I here allude is that Tarquinius Superbus increased the number of the Vestals in order that each tribe might have two. With this we must connect a passage from the tenth book of Livy, where he says that the augurs were to represent the three tribes. The numbers in the Roman colleges of priests were always multiples either of two or of three; the latter was the case with the Vestal Virgins and the great Flamines, and the former with the Augurs, Pontiffs, and Fetiales, who represented only the first two tribes. Previously to the passing of the Ogulnian law the number of augurs was four, and when subsequently five plebeians were added, the basis of this increase was different, it is true, but the ancient rule of the number being a multiple of three was preserved. The number of pontiffs, which was then four, was increased only by four: this might seem to contradict what has just been stated, but it has been overlooked that Cicero speaks of five new ones having been added, for he included the Pontifex Maximus, which Livy does not. In like manner there were twenty Fetiales, ten for each tribe. To the Salii on the Palatine Numa added another brotherhood on the Quirinal; thus we everywhere see a manifest distinction between the first two tribes and the third, the latter being treated as inferior.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.