The whole description of the circumstances under which the fate of Alba was decided is just as manifestly poetical, but we shall dwell upon it for a while in order to show how a semblance of history may arise.

Continuing The Foundation of Rome,

our selection from Roman History by Barthold Georg Niebuhr published in 1848. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in nine easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in The Foundation of Rome.

Time: 753 BC

Place: Rome

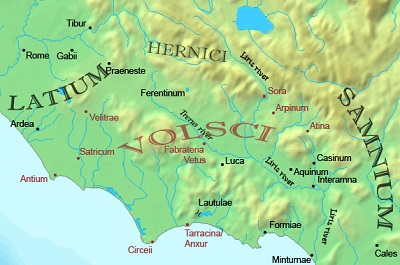

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Such was Rome in the second stage of its development. This period of equalization is one of peace, and is described as the reign of Numa, about whom the traditions are simple and brief. It is the picture of a peaceful condition with a holy man at the head of affairs, like Nicolas von der Flue in Switzerland. Numa was supposed to have been inspired by the goddess.

Egeria, to whom he was married in the grove of the Camenæ, and who introduced him into the choir of her sisters; she melted away in tears at his death, and thus gave her name to the spring which arose out of her tears. Such a peace of forty years, during which no nation rose against Rome, because Numa’s piety was communicated to the surrounding nations, is a beautiful idea, but historically impossible in those times, and manifestly a poetical fiction.

The death of Numa forms the conclusion of the first sæculum, and an entirely new period follows, just as in the Theogony of Hesiod the age of heroes is followed by the iron age; there is evidently a change, and an entirely new order of things is conceived to have arisen. Up to this point we have had nothing except poetry, but with Tullus Hostilius a kind of history begins, that is, events are related which must be taken in general as historical, though in the light in which they are presented to us they are not historical. Thus, for example, the destruction of Alba is historical, and so in all probability is the reception of the Albans at Rome. The conquests of Ancus Martius are quite credible; and they appear like an oasis of real history in the midst of fables. A similar case occurs once in the chronicle of Cologne. In the Abyssinian annals, we find in the thirteenth century a very minute account of one particular event, in which we recognize a piece of contemporaneous history, though we meet with nothing historical either before or after.

The history which then follows is like a picture viewed from the wrong side, like phantasmata; the names of the kings are perfectly fictitious; no man can tell how long the Roman kings reigned, as we do not know how many there were, since it is only for the sake of the number that seven were supposed to have ruled, seven being a number which appears in many relations, especially in important astronomical ones. Hence the chronological statements are utterly worthless. We must conceive as a succession of centuries the period from the origin of Rome down to the times wherein were constructed the enormous works, such as the great drains, the wall of Servius, and others, which were actually executed under the kings and rival the great architectural works of the Egyptians. Romulus and Numa must be entirely set aside; but a long period follows, in which the nations gradually unite and develop themselves until the kingly government disappears and makes way for republican institutions.

But it is nevertheless necessary to relate the history, such as it has been handed down, because much depends upon it. There was not the slightest connection between Rome and Alba, nor is it even mentioned by the historians, though they suppose that Rome received its first inhabitants from Alba; but in the reign of Tullus Hostilius the two cities on a sudden appear as enemies: each of the two nations seeks war, and tries to allure fortune by representing itself as the injured party, each wishing to declare war. Both sent ambassadors to demand reparation for robberies which had been committed. The form of procedure was this: the ambassadors, that is the Fetiales, related the grievances of their city to every person they met, they then proclaimed them in the market-place of the other city, and if, after the expiration of thrice ten days no reparation was made, they said, “We have done enough and now return,” whereupon the elders at home held counsel as to how they should obtain redress. In this formula accordingly the res, that is, the surrender of the guilty and the restoration of the stolen property, must have been demanded. Now it is related that the two nations sent such ambassadors quite simultaneously, but that Tullus Hostilius retained the Alban ambassadors, until he was certain that the Romans at Alba had not obtained the justice due to them, and had therefore declared war. After this he admitted the ambassadors into the senate, and the reply made to their complaint was, that they themselves had not satisfied the demands of the Romans. Livy then continues: bellum in trigesimum diem dixerant. But the real formula is, post trigesimum diem, and we may ask, Why did Livy or the annalist whom he followed make this alteration? For an obvious reason: a person may ride from Rome to Alba in a couple of hours, so that the detention of the Alban ambassadors at Rome for thirty days, without their hearing what was going on in the mean time at Alba, was a matter of impossibility. Livy saw this, and therefore altered the formula. But the ancient poet was not concerned about such things, and without hesitation increased the distance in his imagination, and represented Rome and Alba as great states.

The whole description of the circumstances under which the fate of Alba was decided is just as manifestly poetical, but we shall dwell upon it for a while in order to show how a semblance of history may arise. Between Rome and Alba there was a ditch, Fossa Cluilia or Cloelia, and there must have been a tradition that the Albans had been encamped there; Livy and Dionysius mention that Cluilius, a general of the Albans, had given the ditch its name, having perished there. It was necessary to mention the latter circumstance, in order to explain the fact that afterward their general was a different person, Mettius Fuffetius, and yet to be able to connect the name of that ditch with the Albans. The two states committed the decision of their dispute to champions, and Dionysius says that tradition did not agree as to whether the name of the Roman champions was Horatii or Curiatii, although he himself, as well as Livy, assumes that it was Horatii, probably because it was thus stated by the majority of the annalists. Who would suspect any uncertainty here if it were not for this passage of Dionysius?

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.