In the midst of the solemnities, the Sabine maidens, thirty in number, were carried off, from whom the curiæ received their names: this is the genuine ancient legend, and it proves how small ancient Rome was conceived to have been.

Continuing The Foundation of Rome,

our selection from Roman History by Barthold Georg Niebuhr published in 1848. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in nine easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in The Foundation of Rome.

Time: 753 BC

Place: Rome

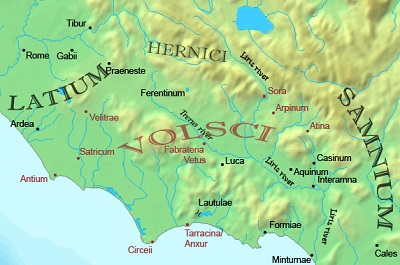

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Among the Greeks it was, as Dionysius states, a general opinion that Rome was a Pelasgian, that is, a Tyrrhenian city, but the authorities from whom he learned this are no longer extant. There is, however, a fragment in which it is stated that Rome was a sister city of Antium and Ardea; here too we must apply the statement from the chronicle of Cumæ, that Evander, who, as an Arcadian, was likewise a Pelasgian, had his palatium on the Palatine. To us he appears of less importance than in the legend, for in the latter he is one of the benefactors of nations, and introduced among the Pelasgians in Italy the use of the alphabet and other arts, just as Damaratus did among the Tyrrhenians in Etruria. In this sense, therefore, Rome was certainly a Latin town, and had not a mixed but a purely Tyrrheno-Pelasgian population. The subsequent vicissitudes of this settlement may be gathered from the allegories.

Romulus now found the number of his fellow-settlers too small; the number of three thousand foot and three hundred horse, which Livy gives from the commentaries of the pontiffs, is worth nothing; for it is only an outline of the later military arrangement transferred to the earliest times. According to the ancient tradition, Romulus’s band was too small, and he opened an asylum on the Capitoline hill. This asylum, the old description states, contained only a very small space, a proof how little these things were understood historically. All manner of people, thieves, murderers, and vagabonds of every kind, flocked thither. This is the simple view taken of the origin of the clients. In the bitterness with which the estates subsequently looked upon one another, it was made a matter of reproach to the Patricians that their earliest ancestors had been vagabonds; though it was a common opinion that the Patricians were descended from the free companions of Romulus, and that those who took refuge in the asylum placed themselves as clients under the protection of the real free citizens. But now they wanted women, and attempts were made to obtain the connubium with neighboring towns, especially perhaps with Antemnæ, which was only four miles distant from Rome, with the Sabines and others. This being refused Romulus had recourse to a stratagem, proclaiming that he had discovered the altar of Consus, the god of counsels, an allegory of his cunning in general. In the midst of the solemnities, the Sabine maidens, thirty in number, were carried off, from whom the curiæ received their names: this is the genuine ancient legend, and it proves how small ancient Rome was conceived to have been. In later times the number was thought too small; it was supposed that these thirty had been chosen by lot for the purpose of naming the curiæ after them; and Valerius Antias fixed the number of the women who had been carried off at five hundred and twenty-seven. The rape is placed in the fourth month of the city, because the consualia fall in August, and the festival commemorating the foundation of the city in April; later writers, as Cn. Gellius, extended this period to four years, and Dionysius found this of course far more credible. From this rape there arose wars, first with the neighboring towns, which were defeated one after another, and at last with the Sabines. The ancient legend contains not a trace of this war having been of long continuance; but in later times it was necessarily supposed to have lasted for a considerable time, since matters were then measured by a different standard. Lucumo and Cælius came to the assistance of Romulus, an allusion to the expedition of Cæles Vibenna, which however belongs to a much later period. The Sabine king, Tatius, was induced by treachery to settle on the hill which is called the Tarpeian arx. Between the Palatine and the Tarpeian rock a battle was fought, in which neither party gained a decisive victory, until the Sabine women threw themselves between the combatants, who agreed that henceforth the sovereignty should be divided between the Romans and the Sabines. According to the annals, this happened in the fourth year of Rome.

But this arrangement lasted only a short time; Tatius was slain during a sacrifice at Lavinium, and his vacant throne was not filled up. During their common reign, each king had a senate of one hundred members, and the two senates, after consulting separately, used to meet, and this was called comitium. Romulus during the remainder of his life ruled alone; the ancient legend knows nothing of his having been a tyrant: according to Ennius he continued, on the contrary, to be a mild and benevolent king, while Tatius was a tyrant. The ancient tradition contained nothing beyond the beginning and the end of the reign of Romulus; all that lies between these points, the war with the Veientines, Fidenates, and so on, is a foolish invention of later annalists. The poem itself is beautiful, but this inserted narrative is highly absurd, as for example the statement that Romulus slew ten thousand Veientines with his own hand. The ancient poem passed on at once to the time when Romulus had completed his earthly career, and Jupiter fulfilled his promise to Mars, that Romulus was the only man whom he would introduce among the gods. According to this ancient legend, the king was reviewing his army near the marsh of Capræ, when, as at the moment of his conception, there occurred an eclipse of the sun and at the same time a hurricane, during which Mars descended in a fiery chariot and took his son up to heaven. Out of this beautiful poem the most wretched stories have been manufactured: Romulus, it is said, while in the midst of his senators was knocked down, cut into pieces, and thus carried away by them under their togas. This stupid story was generally adopted, and that a cause for so horrible a deed might not be wanting, it was related that in his latter years Romulus had become a tyrant, and that the senators took revenge by murdering him.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.