The curia of Rome, a cottage covered with straw, was a faithful memorial of the times when Rome stood buried in the night of history, as a small country town surrounded by its little domain.

Continuing The Foundation of Rome,

our selection from Roman History by Barthold Georg Niebuhr published in 1848. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in nine easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in The Foundation of Rome.

Time: 753 BC

Place: Rome

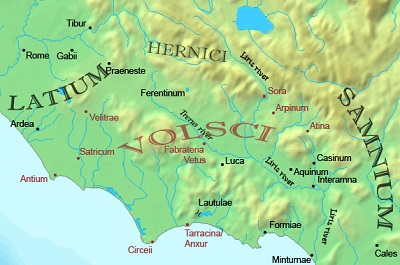

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

After the death of Romulus, the Romans and the people of Tatius quarreled for a long time with each other, the Sabines wishing that one of their nation should be raised to the throne, while the Romans claimed that the new king should be chosen from among them. At length they agreed, it is said, that the one nation should choose a king from the other.

We have now reached the point at which it is necessary to speak of the relation between the two nations, such as it actually existed.

All the nations of antiquity lived in fixed forms, and their civil relations were always marked by various divisions and subdivisions. When cities raise themselves to the rank of nations, we always find a division at first into tribes; Herodotus mentions such tribes in the colonization of Cyrene, and the same was afterward the case at the foundation of Thurii; but when a place existed anywhere as a distinct township, its nature was characterized by the fact of its citizens being at a certain time divided into gentes [Greek: genê], each of which had a common chapel and a common hero. These gentes were united in definite numerical proportions into curiæ [Greek: phratrai]. The gentes are not families, but free corporations, sometimes close and sometimes open; in certain cases the whole body of the state might assign to them new associates; the great council at Venice was a close body, and no one could be admitted whose ancestors had not been in it, and such also was the case in many oligarchical states of antiquity.

All civil communities had a council and an assembly of burghers, that is, a small and a great council; the burghers consisted of the guilds or gentes, and these again were united, as it were, in parishes; all the Latin towns had a council of one hundred members, who were divided into ten curiæ; this division gave rise to the name of decuriones, which remained in use as a title of civic magistrates down to the latest times, and through the lex Julia was transferred to the constitution of the Italian municipia. That this council consisted of one hundred persons has been proved by Savigny, in the first volume of his history of the Roman law. This constitution continued to exist till a late period of the middle ages, but perished when the institution of guilds took the place of municipal constitutions. Giovanni Villani says, that previously to the revolution in the twelfth century there were at Florence one hundred buoni nomini, who had the administration of the city. There is nothing in the German cities which answers to this constitution. We must not conceive those hundred to have been nobles; they were an assembly of burghers and country people, as was the case in our small imperial cities, or as in the small cantons of Switzerland. Each of them represented a gens; and they are those whom Propertius calls patres pelliti. The curia of Rome, a cottage covered with straw, was a faithful memorial of the times when Rome stood buried in the night of history, as a small country town surrounded by its little domain.

The most ancient occurrence which we can discover from the form of the allegory, by a comparison of what happened in other parts of Italy, is a result of the great and continued commotion among the nations of Italy. It did not terminate when the Oscans had been pressed forward from Lake Fucinus to the lake of Alba, but continued much longer. The Sabines may have rested for a time, but they advanced far beyond the districts about which we have any traditions. These Sabines began as a very small tribe, but afterward became one of the greatest nations of Italy, for the Marrucinians, Caudines, Vestinians, Marsians, Pelignians, and in short all the Samnite tribes, the Lucanians, the Oscan part of the Bruttians, the Picentians, and several others were all descended from the Sabine stock, and yet there are no traditions about their settlements except in a few cases. At the time to which we must refer the foundation of Rome, the Sabines were widely diffused. It is said that, guided by a bull, they penetrated into Opica, and thus occupied the country of the Samnites. It was perhaps at an earlier time that they migrated down the Tiber, whence we there find Sabine towns mixed with Latin ones; some of their places also existed on the Anio. The country afterward inhabited by the Sabines was probably not occupied by them till a later period, for Falerii is a Tuscan town, and its population was certainly at one time thoroughly Tyrrhenian.

As the Sabines advanced, some Latin towns maintained their independence, others were subdued; Fidenæ belonged to the former, but north of it all the country was Sabine. Now by the side of the ancient Roma we find a Sabine town on the Quirinal and Capitoline close to the Latin town; but its existence is all that we know about it. A tradition states that there previously existed on the Capitoline a Siculian town of the name of Saturnia, which, in this case, must have been conquered by the Sabines. But whatever we may think of this, as well as of the existence of another ancient town on the Janiculum, it is certain that there were a number of small towns in that district. The two towns could exist perfectly well side by side, as there was a deep marsh between them.

The town on the Palatine may for a long time have been in a state of dependence on the Sabine conqueror whom tradition calls Titus Tatius; hence he was slain during the Laurentine sacrifice, and hence also his memory was hateful. The existence of a Sabine town on the Quirinal is attested by the undoubted occurrence there of a number of Sabine chapels, which were known as late as the time of Varro, and from which he proved that the Sabine ritual was adopted by the Romans. This Sabine element in the worship of the Romans has almost always been overlooked, in consequence of the prevailing desire to look upon everything as Etruscan; but, I repeat, there is no doubt of the Sabine settlement, and that it was the result of a great commotion among the tribes of middle Italy.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.