Arriving at Stadacona on the 11th, measures were taken for maintenance and security during the approaching winter.

Continuing Cartier Explores Canada,

our selection from The History of Canada under French Regime by Henry H. Miles published in 1881. The selection is presented in seven easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Cartier Explores Canada.

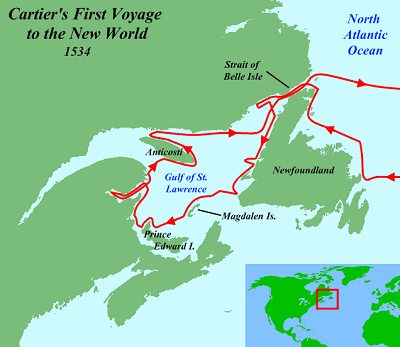

Time: 1534

Place: Canadian Coast

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

At Hochelaga, as previously at Stadacona, the French were received by the natives in a friendly manner. Supplies of fish and maize were freely offered, and, in return, presents of beads, knives, small mirrors, and crucifixes were distributed. Entering into communication with them, Cartier sought information respecting the country higher up the river. From their imperfect intelligence it appears he learned the existence of several great lakes, and that beyond the largest and most remote of these there was another great river which flowed southward. They conducted him to the summit of a mountain behind the town, whence he surveyed the prospect of a wilderness stretching to the south and west as far as the eye could reach, and beautifully diversified by elevations of land and by water. Whatever credit Cartier attached to their vague statements about the geography of their country, he was certainly struck by the grandeur of the neighboring scenery as viewed from the eminence on which he stood. To this he gave the name of Mount Royal, whence the name of Montreal was conferred on the city which has grown up on the site of the ancient Indian town Hochelaga.

According to some accounts, Hochelaga was, even in those days, a place of importance, having subject to it eight or ten outlying settlements or villages.

Anxious to return to Stadacona, and probably placing little confidence in the friendly professions of the natives, Cartier remained at Hochelaga only two days, and commenced his passage down the river on October 4th. His wary mistrust of the Indian character was not groundless, for bands of savages followed along the banks and watched all the proceedings of his party. On one occasion he was attacked by them and narrowly escaped massacre.

Arriving at Stadacona on the 11th, measures were taken for maintenance and security during the approaching winter. Abundant provisions had been already stored up by the natives and assigned for the use of the strangers. A fence or palisade was constructed round the ships, and made as strong as possible, and cannon so placed as to be available in case of any attack. Notwithstanding these precautions, it turned out that, in one essential particular, the preparations for winter were defective. Jacques Cartier and his companions being the first of Europeans to experience the rigors of a Canadian winter, the necessity for warm clothing had not been foreseen when the expedition left France, and now, when winter was upon them, the procuring of a supply was simply impossible. The winter proved long and severe. Masses of ice began to come down the St. Lawrence on November 15th, and, not long afterward, a bridge of ice was formed opposite to Stadacona. Soon the intensity of the cold — such as Cartier’s people had never before experienced — and the want of suitable clothing occasioned much suffering. Then, in December, a disease, but little known to Europeans, broke out among the crew. It was the scurvy, named by the French mal-de-terre.

As described by Cartier, it was very painful, loathsome in its symptoms and effects, as well as contagious. The legs and thighs of the patients swelled, the sinews contracted, and the skin became black. In some cases the whole body was covered with purple spots and sore tumors. After a time the upper parts of the body — the back, arms, shoulders, neck, and face — were all painfully affected. The roof of the mouth, gums, and teeth fell out. Altogether, the sufferers presented a deplorable spectacle.

Many died between December and April, during which period the greatest care was taken to conceal their true condition from the natives. Had this not been done, it is to be feared that Donacona’s people would have forced an entrance and put all to death for the purpose of obtaining the property of the French. In fact, the two interpreters were, on the whole, unfaithful, living entirely at Stadacona; while Donacona, and the Indians generally, showed, in many ways, that, under a friendly exterior, unfavorable feelings reigned in their hearts.

But the attempts to hide their condition from the natives might have been fatal, for the Indians, who also suffered from scurvy, were acquainted with means of curing the disease. It was only by accident that Cartier found out what those means were. He had forbidden the savages to come on board the ships, and when any of them came near the only men allowed to be seen by them were those who were in health. One day, Domagaya was observed approaching. This man, the younger of the two interpreters, was known to have been sick of the scurvy at Stadacona, so that Cartier was much surprised to see him out and well. He contrived to make him relate the particulars of his recovery, and thus found out that a decoction of the bark and foliage of the white spruce-tree furnished the savages with a remedy. Having recourse to this enabled the French captain to arrest the progress of the disease among his own people, and, in a short time, to bring about their restoration to health.

The meeting with Domagaya occurred at a time when the French were in a very sad state — reduced to the brink of despair. Twenty-five of the number had died, while forty more were in expectation of soon following their deceased comrades. Of the remaining forty-five, including Cartier and all the surviving officers, only three or four were really free from disease. The dead could not be buried, nor was it possible for the sick to be properly cared for.

In this extremity, the stout-hearted French captain could think of no other remedy than a recourse to prayers and the setting up of an image of the Virgin Mary in sight of the sufferers. “But,” he piously exclaimed, “God, in his holy grace, looked down in pity upon us, and sent to us a knowledge of the means of cure.” He had great apprehensions of an attack from the savages, for he says in his narrative: “We were in a marvelous state of terror lest the people of the country should ascertain our pitiable condition and our weakness,” and then goes on to relate artifices by which he contrived to deceive them.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.