When he ascended the throne the happy youth saw round him neither competitor to remove nor enemies to punish.

Continuing Commodus’ Bad Reign,

our selection from The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon published in 1788. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Commodus’ Bad Reign.

Time: 180

Place: Rome

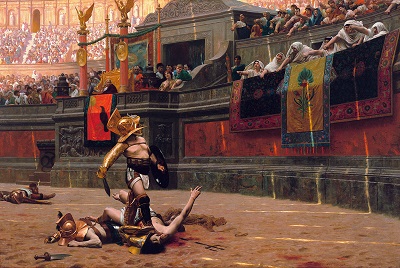

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Most of the crimes which disturb the internal peace of society are produced by the restraints which the necessary but unequal laws of property have imposed on the appetites of mankind by confining to a few the possession of those objects that are coveted by many. Of all our passions and appetites the love of power is of the most imperious and unsociable nature, since the pride of one man requires the submission of the multitude. In the tumult of civil discord, the laws of society lose their force, and their place is seldom supplied by those of humanity. The ardor of contention, the pride of victory, the despair of success, the memory of past injuries, and the fear of future dangers all contribute to inflame the mind and to silence the voice of pity. From such motives almost every page of history has been stained with civil blood; but these motives will not account for the unprovoked cruelties of Commodus, who had nothing to wish and everything to enjoy.

The beloved son of Marcus succeeded to his father, amid the acclamations of the senate and armies; and when he ascended the throne the happy youth saw round him neither competitor to remove nor enemies to punish. In this calm, elevated station it was surely natural that he should prefer the love of mankind to their detestation, the mild glories of his five predecessors to the ignominious fate of Nero and Domitian.

Yet Commodus was not, as he has been represented, a tiger born with an insatiate thirst of human blood, and capable, from his infancy, of the most inhuman actions. Nature had formed him of a weak rather than a wicked disposition. His simplicity and timidity rendered him the slave of his attendants, who gradually corrupted his mind. His cruelty, which at first obeyed the dictates of others, degenerated into habit, and at length became the ruling passion of his soul.

Upon the death of his father, Commodus found himself embarrassed with the command of a great army, and the conduct of a difficult war against the Quadi and Marcomanni. The servile and profligate youths whom Marcus had banished soon regained their station and influence about the new Emperor. They exaggerated the hardships and dangers of a campaign in the wild countries beyond the Danube; and they assured the indolent prince that the terror of his name and the arms of his lieutenants would be sufficient to complete the conquest of the dismayed barbarians, or to impose such conditions as were more advantageous than any conquest. By a dexterous application to his sensual appetites they compared the tranquillity, the splendor, the refined pleasures of Rome with the tumult of a Pannonian camp, which afforded neither leisure nor materials for luxury. Commodus listened to the pleasing advice, but while he hesitated between his own inclination and the awe which he still retained for his father’s counselors, the summer insensibly elapsed, and his triumphal entry into the capital was deferred till the autumn. His graceful person, popular address, and imagined virtues attracted the public favor; the honorable peace which he had recently granted to the barbarians diffused a universal joy; his impatience to revisit Rome was fondly ascribed to the love of his country; and his dissolute course of amusements was faintly condemned in a prince of nineteen years of age.

During the three first years of his reign the forms, and even the spirit, of the old administration were maintained by those faithful counsellors to whom Marcus had recommended his son, and for whose wisdom and integrity Commodus still entertained a reluctant esteem. The young prince and his profligate favorites revelled in all the license of sovereign power; but his hands were yet unstained with blood; and he had even displayed a generosity of sentiment which might perhaps have ripened into solid virtue.[*] A fatal incident decided his fluctuating character.

* Manilius, the confidential secretary of Avidius Cassius, was discovered after he had lain concealed several years. The Emperor nobly relieved the public anxiety by refusing to see him, and burning his papers without opening them.

One evening, as the Emperor was returning to the palace through a dark and narrow portico in the Amphitheatre, an assassin, who waited his passage, rushed upon him with a drawn sword, loudly exclaiming, “The senate sends you this.” The menace prevented the deed; the assassin was seized by the guards, and immediately revealed the authors of the conspiracy. It had been formed, not in the state, but within the walls of the palace. Lucilla, the Emperor’s sister, and widow of Lucius Verus, impatient of the second rank, and jealous of the reigning empress, had armed the murderer against her brother’s life. She had not ventured to communicate the black design to her second husband, Claudius Pompeianus, a senator of distinguished merit and unshaken loyalty; but among the crowd of her lovers — for she imitated the manners of Faustina — she found men of desperate fortunes and wild ambition, who were prepared to serve her more violent as well as her tender passions. The conspirators experienced the rigor of justice, and the abandoned princess was punished, first with exile, and afterward with death.

But the words of the assassin sunk deep into the mind of Commodus, and left an indelible impression of fear and hatred against the whole body of the senate. Those whom he had dreaded as importunate ministers he now suspected as secret enemies. The delators, a race of men discouraged and almost extinguished under the former reigns, again became formidable, as soon as they discovered that the Emperor was desirous of finding disaffection and treason in the senate. That assembly, whom Marcus had ever considered as the great council of the nation, was composed of the most distinguished of the Romans; and distinction of every kind soon became criminal. The possession of wealth stimulated the diligence of the informers; rigid virtue implied a tacit censure of the irregularities of Commodus; important services implied a dangerous superiority of merit; and the friendship of the father always insured the aversion of the son. Suspicion was equivalent to proof; trial to condemnation. The execution of a considerable senator was attended with the death of all who might lament or revenge his fate, and when Commodus had once tasted human blood he became incapable of pity or remorse.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.