During this night of suspense and terror, the Princess of Wales held a council with the ministers in the Tower.

Continuing Rebellion of Wat Tyler,

our selection from The History of England, From the First Invasion by the Romans to the Accession of Henry VIII by John Lingard published in 1819. The selection is presented in three easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages

Previously in Rebellion of Wat Tyler.

Time: 1381

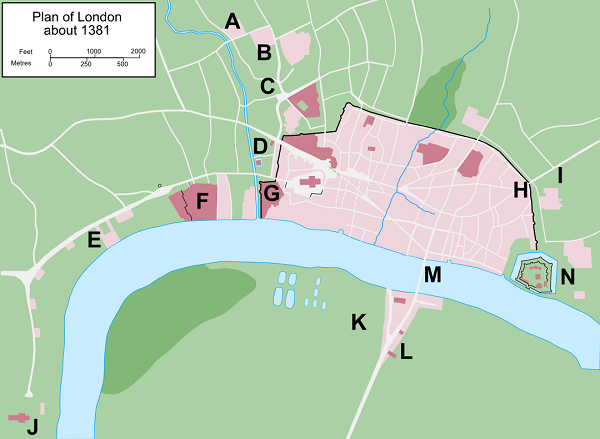

Place: Southwark

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

By letters and messengers the knowledge of these proceedings was carefully propagated through the neighboring counties. Everywhere the people had been prepared; and in a few days the flame spread from the southern coast of Kent to the right bank of the Humber. In all places the insurgents regularly pursued the same course. They pillaged the manors of their lords, demolished the houses, and burned the court rolls; cut off the heads of every justice and lawyer and juror who fell into their hands; and swore all others to be true to King Richard and the commons; to admit of no king of the name of John; and to oppose all taxes but fifteenths, the ancient tallage paid by their fathers. The members of the council saw, with astonishment, the sudden rise and rapid spread of the insurrection; and, bewildered by their fears and ignorance, knew not whom to trust or what measures to pursue.

The first who encountered the rabble on Blackheath was the Princess of Wales, the King’s mother, on her return from a pilgrimage to Canterbury. She liberated herself from danger by her own address; and a few kisses from “the fair maid of Kent” purchased the protection of the leaders, and secured the respect of their followers. She was permitted to join her son, who, with his cousin Henry, Earl of Derby, Simon, Archbishop of Canterbury and Chancellor, Sir Robert Hales, master of the Knights of St. John and treasurer, and about one hundred sergeants and knights had left the castle of Windsor, and repaired for greater security to the Tower of London. The next morning the King in his barge descended the river to receive the petitions of the insurgents. To the number of ten thousand, with two banners of St. George, and sixty pennons, they waited his arrival at Rotherhithe; but their horrid yells and uncouth appearance so intimidated his attendants, that instead of permitting him to land, they took advantage of the tide, and returned with precipitation. Tyler and Straw, irritated by this disappointment, led their men into Southwark, where they demolished the houses belonging to the Marshalsea and the king’s bench, while another party forced their way into the palace of the Archbishop at Lambeth, and burned the furniture with the records belonging to the chancery.

The next morning they were allowed to pass in small companies, according to their different townships, over the bridge into the city. The populace joined them; and as soon as they had regaled themselves at the cost of the richer inhabitants, the work of devastation commenced. They demolished Newgate, and liberated the prisoners; plundered and destroyed the magnificent palace of the Savoy, belonging to the Duke of Lancaster; burned the temple with the books and records; and dispatched a party to set fire to the house of the Knights Hospitallers at Clerkenwell, which had been lately built by Sir Robert Hales. To prove, however, that they had no views of private emolument, a proclamation was issued forbidding any one to secrete part of the plunder; and so severely was the prohibition enforced that the plate was hammered and cut into small pieces, the precious stones were beaten to powder, and one of the rioters, who had concealed a silver cup in his bosom, was immediately thrown, with his prize, into the river. To every man whom they met they put the question, “With whom holdest thou?” and unless he gave the proper answer, “With King Richard and the commons,” he was instantly beheaded. But the principal objects of their cruelty were the natives of Flanders. They dragged thirteen Flemings out of one church, seventeen out of another, and thirty-two out of the Vintry, and struck off their heads with shouts of triumph and exultation. In the evening, wearied with the labor of the day, they dispersed through the streets, and indulged in every kind of debauchery.

During this night of suspense and terror, the Princess of Wales held a council with the ministers in the Tower. The King’s uncles were absent; the garrison, though perhaps able to defend the place, was too weak to put down the insurgents; and a resolution was taken to try the influence of promises and concession. In the morning the Tower Hill was seen covered with an immense multitude, who prohibited the introduction of provisions, and with loud cries demanded the heads of the chancellor and treasurer. In return, a herald ordered them, by proclamation, to retire to Mile End, where the King would assent to all their demands. Immediately the gates were thrown open. Richard with a few unarmed attendants rode forward; the best intentioned of the crowd followed him, and at Mile End he saw himself surrounded with sixty thousand petitioners. Their demands were reduced to four: the abolition of slavery; the reduction of the rent of land to fourpence the acre; the free liberty of buying and selling in all fairs and markets; and a general pardon for past offences. A charter to that effect was engrossed for each parish and township; during the night thirty clerks were employed in transcribing a sufficient number of copies; they were sealed and delivered in the morning; and the whole body, consisting chiefly of the men of Essex and Hertfordshire, retired, bearing the King’s banner as a token that they were under his protection.

But Tyler and Straw had formed other and more ambitious designs. The moment the King was gone, they rushed, at the head of four hundred men, into the Tower. The Archbishop, who had just celebrated mass, Sir Robert Hales, William Apuldore, the King’s confessor, Legge, the farmer of the tax, and three of his associates, were seized, and led to immediate execution. As no opposition was offered, they searched every part of the Tower, burst into the private apartment of the Princess, and probed her bed with their swords. She fainted, and was carried by her ladies to the river, which she crossed in a covered barge. The royal wardrobe, a house in Carter Lane, was selected for her residence.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.