The sound revealed that the horse was hollow, but the Trojans heeded not this warning of possible fraud.

Continuing Fall of Troy,

our selection from History of Greece by George Grote published in 1846. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages. The selection is presented in eight easy 5 minute installments.

Previously in Fall of Troy.

Time: 1184 BC

Place: Troy

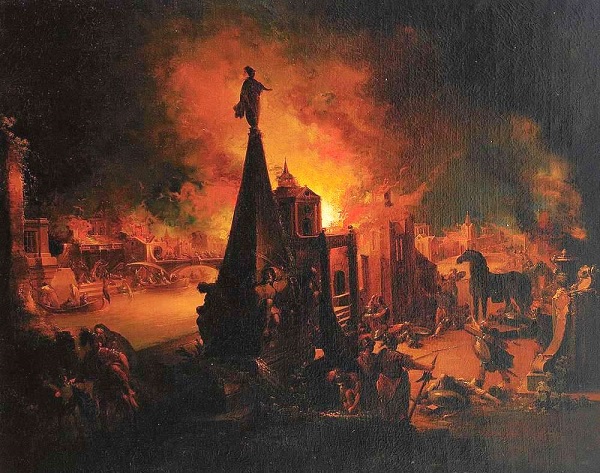

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Odysseus now learned from Helenus, son of Priam, whom he had captured in an ambuscade, that Troy could not be taken unless both Philoctetes and Neoptolemus, son of Achilles, could be prevailed upon to join the besiegers. The former, having been stung in the foot by a serpent, and becoming insupportable to the Greeks from the stench of his wound, had been left at Lemnos in the commencement of the expedition, and had spent ten years in misery on that desolate island; but he still possessed the peerless bow and arrows of Heracles, which were said to be essential to the capture of Troy. Diomedes fetched Philoctetes from Lemnos to the Grecian camp, where he was healed by the skill of Machaon, and took an active part against the Trojans — engaging in single combat with Paris, and killing him with one of the Heracleian arrows. The Trojans were allowed to carry away for burial the body of this prince, the fatal cause of all their sufferings; but not until it had been mangled by the hand of Menelaus. Odysseus went to the island of Scyros to invite Neoptolemus to the army. The untried but impetuous youth, gladly obeying the call, received from Odysseus his father’s armor; while, on the other hand, Eurypylus, son of Telephus, came from Mysia as auxiliary to the Trojans and rendered to them valuable service turning the tide of fortune for a time against the Greeks, and killing some of their bravest chiefs, among whom were numbered Peneleos, and the unrivalled leech Machaon. The exploits of Neoptolemus were numerous, worthy of the glory of his race and the renown of his father. He encountered and slew Eurypylus, together with numbers of the Mysian warriors: he routed the Trojans and drove them within their walls, from whence they never again emerged to give battle: and he was not less distinguished for good sense and persuasive diction than for forward energy in the field.

Troy, however, was still impregnable so long as the Palladium, a statue given by Zeus himself to Dardanus, remained in the citadel; and great care had been taken by the Trojans not only to conceal this valuable present, but to construct other statues so like it as to mislead any intruding robber. Nevertheless, the enterprising Odysseus, having disguised his person with miserable clothing and self-inflicted injuries, found means to penetrate into the city and to convey the Palladium by stealth away. Helen alone recognized him; but she was now anxious to return to Greece, and even assisted Odysseus in concerting means for the capture of the town.

To accomplish this object, one final stratagem was resorted to. By the hands of Epeius of Panopeus, and at the suggestion of Athene, a capacious hollow wooden horse was constructed, capable of containing one hundred men. In the inside of this horse the elite of the Grecian heroes, Neoptolemus, Odysseus, Menelaus, and others, concealed themselves while the entire Grecian army sailed away to Tenedos, burning their tents and pretending to have abandoned the siege. The Trojans, overjoyed to find themselves free, issued from the city and contemplated with astonishment the fabric which their enemies had left behind. They long doubted what should be done with it; and the anxious heroes from within heard the surrounding consultations, as well as the voice of Helen when she pronounced their names and counterfeited the accents of their wives. Many of the Trojans were anxious to dedicate it to the gods in the city as a token of gratitude for their deliverance; but the more cautious spirits inculcated distrust of an enemy’s legacy. Laocoon, the priest of Poseidon, manifested his aversion by striking the side of the horse with his spear.

The sound revealed that the horse was hollow, but the Trojans heeded not this warning of possible fraud. The unfortunate Laocoon, a victim to his own sagacity and patriotism, miserably perished before the eyes of his countrymen, together with one of his sons: two serpents being sent expressly by the gods out of the sea to destroy him. By this terrific spectacle, together with the perfidious counsels of Simon — a traitor whom the Greeks had left behind for the special purpose of giving false information — the Trojans were induced to make a breach in their own walls, and to drag the fatal fabric with triumph and exultation into their city.

The destruction of Troy, according to the decree of the gods, was now irrevocably sealed. While the Trojans indulged in a night of riotous festivity, Simon kindled the fire-signal to the Greeks at Tenedos, loosening the bolts of the wooden horse, from out of which the enclosed heroes descended. The city, assailed both from within and from without, was thoroughly sacked and destroyed, with the slaughter or captivity of the larger portion of its heroes as well as its people. The venerable Priam perished by the hand of Neoptolemus, having in vain sought shelter at the domestic altar of Zeus Herceius. But his son Deiphobus, who since the death of Paris had become the husband of Helen, defended his house desperately against Odysseus and Menelaus, and sold his life dearly. After he was slain, his body was fearfully mutilated by the latter.

Thus was Troy utterly destroyed — the city, the altars and temples, and the population. Æneas and Antenor were permitted to escape, with their families, having been always more favorably regarded by the Greeks than the remaining Trojans. According to one version of the story they had betrayed the city to the Greeks: a panther’s skin had been hung over the door of Antenor’s house as a signal for the victorious besiegers to spare it in general plunder. In the distribution of the principal captives, Astyanax, the infant son of Hector, was cast from the top of the wall and killed by Odysseus or Neoptolemus: Polyxena, the daughter of Priam, was immolated on the tomb of Achilles, in compliance with a requisition made by the shade of the deceased hero to his countrymen; while her sister Cassandra was presented as a prize to Agamemnon. She had sought sanctuary at the altar of Athene, where Ajax, the son of Oileus, making a guilty attempt to seize her, had drawn both upon himself and upon the army the serious wrath of the goddess, insomuch that the Greeks could hardly be restrained from stoning him to death. Andromache and Helenus were both given to Neoptolemus, who, according to the Ilias Minor, carried away also Æneas as his captive.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.