Today’s installment concludes Rebellion of Wat Tyler,

our selection from The History of England, From the First Invasion by the Romans to the Accession of Henry VIII by John Lingard published in 1819.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of three thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Rebellion of Wat Tyler.

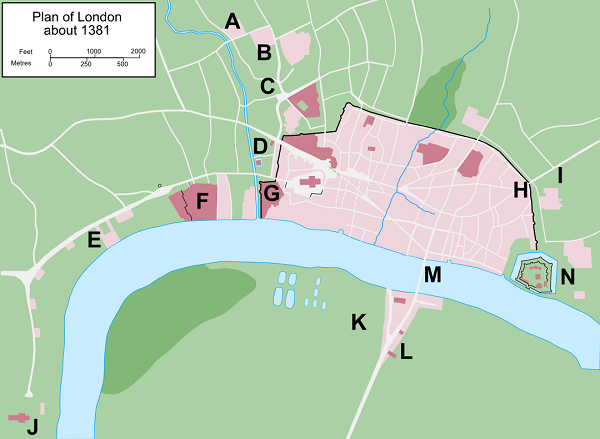

Time: 1381

Place: London

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The King joined his mother at the wardrobe; and the next morning, as he rode through Smithfield with sixty horsemen, encountered Tyler at the head of twenty thousand insurgents. Three different charters had been sent to that demagogue, who contemptuously refused them all. As soon as he saw Richard, he made a sign to his followers to halt, and boldly rode up to the King. A conversation immediately began. Tyler, as he talked, affected to play with his dagger; at last he laid his hand on the bridle of his sovereign; but at the instant Walworth, the Lord Mayor, jealous of his design, plunged a short sword into his throat. He spurred his horse, rode about a dozen yards, fell to the ground, and was dispatched by Robert Standish, one of the King’s esquires. The insurgents, who witnessed the transaction, drew their bows to revenge the fall of their leader, and Richard would inevitably have lost his life had he not been saved by his own intrepidity. Galloping up to the archers he exclaimed: “What are ye doing, my lieges? Tyler was a traitor. Come with me, and I will be your leader.” Wavering and disconcerted, they followed him into the fields of Islington, whither a force of one thousand men-at-arms, which had been collected by the Lord Mayor and Sir Robert Knowles, hastened to protect the young King; and the insurgents, falling on their knees, begged for mercy. Many of the royalists demanded permission to punish them for their past excesses; but Richard firmly refused, ordered the suppliants to return to their homes, and by proclamation forbade, under pain of death, any stranger to pass the night in the city.

On the southern coast the excesses of the insurgents reached as far as Winchester; on the eastern, to Beverley and Scarborough; and, if we reflect that in every place they rose about the same time, and uniformly pursued the same system, we may discover reason to suspect that they acted under the direction of some acknowledged though invisible leader. The nobility and gentry, intimidated by the hostility of their tenants, and distressed by contradictory reports, sought security within the fortifications of their castles. The only man who behaved with promptitude and resolution was Henry Spenser, the young and warlike Bishop of Norwich. In the counties of Norfolk, Cambridge, and Huntington tranquility was restored and preserved by this singular prelate, who successively exercised the offices of general, judge, and priest. In complete armor he always led his followers to the attack; after the battle he sat in judgment on his prisoners; and before execution he administered to them the aids of religion. But as soon as the death of Tyler and the dispersion of the men of Kent and Essex were known, thousands became eager to display their loyalty; and knights and esquires from every quarter poured into London to offer their services to the King. At the head of forty thousand horse he published proclamations, revoking the charters of manumission which he had granted, commanding the villeins to perform their usual services, and prohibiting illegal assemblies and associations. In several parts the commons threatened to renew the horrors of the late tumult in defence of their liberties; but the approach of the royal army dismayed the disaffected in Kent; the loss of five hundred men induced the insurgents of Essex to sue for pardon; and numerous executions in different counties effectually crushed the spirit of resistance. Among the sufferers were Lister and Westbroom, who had assumed the title and authority of kings in Norfolk and Suffolk; and Straw and Ball, the itinerant preachers, who have been already mentioned, and whose sermons were supposed to have kindled and nourished the insurrection.

When the parliament met, the two houses were informed by the Chancellor, that the King had revoked the charters of emancipation, which he had been compelled to grant to the villeins, but at the same time wished to submit to their consideration whether it might not be wise to abolish the state of bondage altogether. The minds of the great proprietors were not, however, prepared for the adoption of so liberal a measure; and both lords and commons unanimously replied that no man could deprive them of the services of their villeins without their consent; that they had never given that consent, and never would be induced to give it, either through persuasion or violence. The King yielded to their obstinacy; and the charters were repealed by authority of parliament. The commons next deliberated, and presented their petitions. They attributed the insurrection to the grievances suffered by the people from: 1. The purveyors, who were said to have exceeded all their predecessors in insolence and extortion; 2. From the rapacity of the royal officers in the chancery and exchequer, and the courts of king’s bench and common pleas; 3. From the banditti, called maintainers, who, in different counties, supported themselves by plunder, and, arming in defense of each other, set at defiance all the provisions of the law; and 4. From the repeated aids and taxes, which had impoverished the people and proved of no service to the nation. To silence these complaints, a commission of inquiry was appointed; the courts of law and the King’s household were subjected to regulations of reform, and severe orders were published for the immediate suppression of illegal associations. But the demand of a supply produced a very interesting altercation. The commons refused, on the ground that the imposition of a new tax would goad the people to a second insurrection. They found it, however, necessary to request of the King a general pardon for all illegal acts committed in the suppression of the insurgents, and received for answer that it was customary for the commons to make their grants before the King bestowed his favors. When the subsidy was again pressed on their attention they replied that they should take time to consider it, but were told that the King would also take time to consider of their petition. At last they yielded; the tax upon wool, wool-fells, and leather was continued for five years, and in return a general pardon was granted for all loyal subjects, who had acted illegally in opposing the rebels, and for the great body of the insurgents, who had been misled by the declamations of the demagogues.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Rebellion of Wat Tyler by John Lingard from his book The History of England, From the First Invasion by the Romans to the Accession of Henry VIII published in 1819. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Rebellion of Wat Tyler here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

394662 351917This internet site is my breathing in, extremely wonderful layout and perfect content material material . 803854